Preamble

For your convenience, I have listed below other post on Japanese textiles on this blogspot.

Discharge Thundercloud

The Basic Kimono Pattern

The Kimono and Japanese Textile Designs

Traditional Japanese Arabesque Patterns - Part I

Textile Dyeing Patterns of Japan

Traditional Japanese Arabesque Patterns - Part II

Sarasa Arabesque Patterns

Contemporary Japanese Textile Creations

Shibori (Tie-Dying)

History of the Kimono

A Textile Tour of Japan - Part I

A Textile Tour of Japan - Part II

The History of the Obi

Japanese Embroidery (Shishu)

Japanese Dyed Textiles

Aizome (Japanese Indigo Dyeing)

Stencil-Dyed Indigo Arabesque Patterns

Japanese Paintings on Silk

Tsutsugaki - Freehand Paste-Resist Dyeing

Street Play in Tokyo

Birds and Flowers in Japanese Textile Designs

Japanese Colors and Inks on Paper From the Idemitsu Collection

Yuzen: Multicolored Past-Resist Dyeing - Part I

Yuzen: Multi-colored Paste-Resist Dyeing - Part II

Katazome (Stencil Dyeing) - Part I

Katazome (Stencil Dyeing) - Part II

Katazome (Stencil Dyeing) - Part III

Aizome (Japanese Indigo Dyeing[1])

There is a certain mystery associated with indigo. In Japan, dyers revere it and pray to their god, Aizen Myo-o, for good fortune in their work.

Aizen Myo-o, Japan, Kamakura period, ca. 14th Century.

They carefully tend the dye vat and give it the respect they would give to a friend. They stir it daily to keep it alive, and replenish it when necessary. Indigo is the principal dyeing substance they use to transform cotton, hemp cloth, ramie, and silk into rich blue masterpieces in a process called aizome.

Drying the indigo-dyed thread in the sun[1]. Courtesy of reference[1].

When cotton was introduced into Japan in the fifteenth century, indigo found its own best friend since both were perfectly matched. Indigo beautifully colored the fibers of this difficult-to-dye fabric, while at the same time it strengthened its fibers by building up layers on them. Cotton was also much softer than the rough hemp fibers that had been available before its appearance. For these reasons, farmers began to plant cotton in place of rice, making it abundant and easily accessible. It was also believed that the ammonia in the indigo repelled mosquitoes and snakes, making indigo-dyed clothing perfect for farmers and field workers. With the availability of cotton and the practicality of the combination of it with indigo, indigo increased in popularity.

Stencil-dyed furisode with maple-leaf, cherry blossom, pine-needle and pine-cone motifs on an indigo background[1].

Edo Period (1603 - 1868).

Tokyo National Museum.

Courtesy of reference[1].

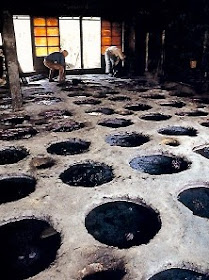

Indigo can be produced in a wide variety of shades, ranging from very pale to almost black. The depth of color is governed by either the strength of the dye into which the fibers are immersed or the number of times the fibers are dipped in the indigo. The vat must be very strong when the fabric to be dyed is covered with paste, as it is in the paste resist dyeing called katazome, because the paste cannot withstand lengthy exposure to moisture. But when dyeing yarn or thread for weaving, paste must not be used, so the dye can be weaker and the number of dips increased according to the depth of color desired. For these reasons, large hand-dyeing houses have vats of different strengths. They are sunk into the ground in sets of four. In the center of each group of four vats is a fire hole, which is lit when the weather turns cold in order to keep the indigo at the proper temperature for dyeing.

Indigo plants.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Indigo vats buried in the ground. The small holes are heat sources[1]. Courtesy of reference[1].

Using a bamboo rake to turn over the indigo leaves during the fermentation process to adjust the temperature[1].

Courtesy reference[1].

Spreading water on the indigo leaves to provide the moisture that assists in the fermentation process[1].

Courtesy of reference[1].

Checking the condition of the indigo in the vat[1].

Courtesy of reference[1].

It is indigo that makes the beautiful blue of yukata fabric. Developed in the Genroku era (1688 - 1704) the yulara was first worn in the bath houses of Kyoto and Osaka, and was soon seen on the streets. The rich merchants of the Edo period, forbidden to wear silk, turned to the dyers for innovative ideas, and this popular item of clothing was developed. Especially favored by courtesans and men about town, its popularity increased until it reached a peak in the Meiji period (1868 - 1912).

Stencil-dyed indigo on cotton and ramie[1].

Courtesy of reference[1].

Yukata fabric was originally dyed by applying a paste to both sides of the fabric through a stencil before dyeing, but the process has been modernized. Today, a roll of fabric is stencilled with paste, sprinkled with sawdust, and folded. The dye is then applied to the fabric and pulled down through the layers of material using a vacuum. The paste is removed, and then the cloth is exposed to air. This exposure is essential in the process of indigo dyeing, because the oxygen in the air causes it to turn blue. The range of blue-and-white designs includes dots, checks, birds, flowers, landscapes, the scrolling plant motive known as karakusa, and small all-over designs known as komon.

Yukata fabric is used today for casual summer wear. Heavier cotton is used for farmer's clothes, the tradesman's half length coat called a hanten, kimono-shaped stuff bedcovers (yogi), square wrapping cloths (furoshiki), quilt covers (futonji),and decorative door curtains cum room dividers (noren). The size of the pattern varies according to the size of the piece being made. Commercial noren for instance, must be wide enough to cover the width of a door opening and adequately advertise the name of the shop. Their designs are usually large and simple, while yukata motifs can be small and very complex.

The different shades of indigo that can be obtained are clearly shown in these cotton yukata[1].

Courtesy of reference[1].

A style of indigo dyeing called chayazome is said to have been developed in Kyoto in the seventeenth century by Chaysa Sori, a feudal lord serving the Ashikaga clan who had learnt this technique via trade with foreign countries. The Chayas eventually gave up their samurai status to become merchants, supplying the high-ranking ladies of the shogun's household with exquisite, elegant, and refined Chaya-dyed unlined summer kimono (katabira).

Chayazome was done on very high-quality light-weight pure white hemp. The fiber was grown near Nara and bleached and aged a full year before dyeing - always in a cool blue shade. A special technique was used to apply the resist paste to both sides of the fabric in all areas to be reserved from the dye, and the extremely detailed designs were done in indigo. The fine blue lines, regular and even in width throughout the entire length of fabric, stretched uninterrupted against a white background. Chayazome robes were perfect and luxurious summer wear: cool in color, light in weight, and usually decorated with refreshing designs of flowing streams or seashore scenes. Touches of gold couching and embroidery emphasized their luxury.

Chayazome katabira. Scenery dyed in indigo on white ramie, with gold embroidery[1].

Edo period (1603 - 1868)[1].

National Museum of Japanese History.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Reference:

[1] S. Yang and R. ZM. Narasin, Textile Art of Japan, Tokyo (1989).

For your convenience, I have listed below other post on Japanese textiles on this blogspot.

Discharge Thundercloud

The Basic Kimono Pattern

The Kimono and Japanese Textile Designs

Traditional Japanese Arabesque Patterns - Part I

Textile Dyeing Patterns of Japan

Traditional Japanese Arabesque Patterns - Part II

Sarasa Arabesque Patterns

Contemporary Japanese Textile Creations

Shibori (Tie-Dying)

History of the Kimono

A Textile Tour of Japan - Part I

A Textile Tour of Japan - Part II

The History of the Obi

Japanese Embroidery (Shishu)

Japanese Dyed Textiles

Aizome (Japanese Indigo Dyeing)

Stencil-Dyed Indigo Arabesque Patterns

Japanese Paintings on Silk

Tsutsugaki - Freehand Paste-Resist Dyeing

Street Play in Tokyo

Birds and Flowers in Japanese Textile Designs

Japanese Colors and Inks on Paper From the Idemitsu Collection

Yuzen: Multicolored Past-Resist Dyeing - Part I

Yuzen: Multi-colored Paste-Resist Dyeing - Part II

Katazome (Stencil Dyeing) - Part I

Katazome (Stencil Dyeing) - Part II

Katazome (Stencil Dyeing) - Part III

Aizome (Japanese Indigo Dyeing[1])

There is a certain mystery associated with indigo. In Japan, dyers revere it and pray to their god, Aizen Myo-o, for good fortune in their work.

Aizen Myo-o, Japan, Kamakura period, ca. 14th Century.

They carefully tend the dye vat and give it the respect they would give to a friend. They stir it daily to keep it alive, and replenish it when necessary. Indigo is the principal dyeing substance they use to transform cotton, hemp cloth, ramie, and silk into rich blue masterpieces in a process called aizome.

Drying the indigo-dyed thread in the sun[1]. Courtesy of reference[1].

When cotton was introduced into Japan in the fifteenth century, indigo found its own best friend since both were perfectly matched. Indigo beautifully colored the fibers of this difficult-to-dye fabric, while at the same time it strengthened its fibers by building up layers on them. Cotton was also much softer than the rough hemp fibers that had been available before its appearance. For these reasons, farmers began to plant cotton in place of rice, making it abundant and easily accessible. It was also believed that the ammonia in the indigo repelled mosquitoes and snakes, making indigo-dyed clothing perfect for farmers and field workers. With the availability of cotton and the practicality of the combination of it with indigo, indigo increased in popularity.

Stencil-dyed furisode with maple-leaf, cherry blossom, pine-needle and pine-cone motifs on an indigo background[1].

Edo Period (1603 - 1868).

Tokyo National Museum.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Indigo can be produced in a wide variety of shades, ranging from very pale to almost black. The depth of color is governed by either the strength of the dye into which the fibers are immersed or the number of times the fibers are dipped in the indigo. The vat must be very strong when the fabric to be dyed is covered with paste, as it is in the paste resist dyeing called katazome, because the paste cannot withstand lengthy exposure to moisture. But when dyeing yarn or thread for weaving, paste must not be used, so the dye can be weaker and the number of dips increased according to the depth of color desired. For these reasons, large hand-dyeing houses have vats of different strengths. They are sunk into the ground in sets of four. In the center of each group of four vats is a fire hole, which is lit when the weather turns cold in order to keep the indigo at the proper temperature for dyeing.

Indigo plants.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Indigo vats buried in the ground. The small holes are heat sources[1]. Courtesy of reference[1].

Using a bamboo rake to turn over the indigo leaves during the fermentation process to adjust the temperature[1].

Courtesy reference[1].

Spreading water on the indigo leaves to provide the moisture that assists in the fermentation process[1].

Courtesy of reference[1].

Checking the condition of the indigo in the vat[1].

Courtesy of reference[1].

It is indigo that makes the beautiful blue of yukata fabric. Developed in the Genroku era (1688 - 1704) the yulara was first worn in the bath houses of Kyoto and Osaka, and was soon seen on the streets. The rich merchants of the Edo period, forbidden to wear silk, turned to the dyers for innovative ideas, and this popular item of clothing was developed. Especially favored by courtesans and men about town, its popularity increased until it reached a peak in the Meiji period (1868 - 1912).

Stencil-dyed indigo on cotton and ramie[1].

Courtesy of reference[1].

Yukata fabric was originally dyed by applying a paste to both sides of the fabric through a stencil before dyeing, but the process has been modernized. Today, a roll of fabric is stencilled with paste, sprinkled with sawdust, and folded. The dye is then applied to the fabric and pulled down through the layers of material using a vacuum. The paste is removed, and then the cloth is exposed to air. This exposure is essential in the process of indigo dyeing, because the oxygen in the air causes it to turn blue. The range of blue-and-white designs includes dots, checks, birds, flowers, landscapes, the scrolling plant motive known as karakusa, and small all-over designs known as komon.

Yukata fabric is used today for casual summer wear. Heavier cotton is used for farmer's clothes, the tradesman's half length coat called a hanten, kimono-shaped stuff bedcovers (yogi), square wrapping cloths (furoshiki), quilt covers (futonji),and decorative door curtains cum room dividers (noren). The size of the pattern varies according to the size of the piece being made. Commercial noren for instance, must be wide enough to cover the width of a door opening and adequately advertise the name of the shop. Their designs are usually large and simple, while yukata motifs can be small and very complex.

The different shades of indigo that can be obtained are clearly shown in these cotton yukata[1].

Courtesy of reference[1].

A style of indigo dyeing called chayazome is said to have been developed in Kyoto in the seventeenth century by Chaysa Sori, a feudal lord serving the Ashikaga clan who had learnt this technique via trade with foreign countries. The Chayas eventually gave up their samurai status to become merchants, supplying the high-ranking ladies of the shogun's household with exquisite, elegant, and refined Chaya-dyed unlined summer kimono (katabira).

Chayazome was done on very high-quality light-weight pure white hemp. The fiber was grown near Nara and bleached and aged a full year before dyeing - always in a cool blue shade. A special technique was used to apply the resist paste to both sides of the fabric in all areas to be reserved from the dye, and the extremely detailed designs were done in indigo. The fine blue lines, regular and even in width throughout the entire length of fabric, stretched uninterrupted against a white background. Chayazome robes were perfect and luxurious summer wear: cool in color, light in weight, and usually decorated with refreshing designs of flowing streams or seashore scenes. Touches of gold couching and embroidery emphasized their luxury.

Chayazome katabira. Scenery dyed in indigo on white ramie, with gold embroidery[1].

Edo period (1603 - 1868)[1].

National Museum of Japanese History.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Reference:

[1] S. Yang and R. ZM. Narasin, Textile Art of Japan, Tokyo (1989).

No comments:

Post a Comment