Preamble

For your convenience, I have listed below other post on Japanese textiles on this blogspot.

Discharge Thundercloud

The Basic Kimono Pattern

The Kimono and Japanese Textile Designs

Traditional Japanese Arabesque Patterns - Part I

Textile Dyeing Patterns of Japan

Traditional Japanese Arabesque Patterns - Part II

Sarasa Arabesque Patterns

Contemporary Japanese Textile Creations

Shibori (Tie-Dying)

History of the Kimono

A Textile Tour of Japan - Part I

A Textile Tour of Japan - Part II

The History of the Obi

Japanese Embroidery (Shishu)

Japanese Dyed Textiles

Aizome (Japanese Indigo Dyeing)

Stencil-Dyed Indigo Arabesque Patterns

Japanese Paintings on Silk

Tsutsugaki - Freehand Paste-Resist Dyeing

Street Play in Tokyo

Birds and Flowers in Japanese Textile Designs

Japanese Colors and Inks on Paper From the Idemitsu Collection

Yuzen: Multicolored Past-Resist Dyeing - Part I

Yuzen: Multi-colored Paste-Resist Dyeing - Part II

Katazome (Stencil Dyeing) - Part I

Katazome (Stencil Dyeing) - Part II

Katazome (Stencil Dyeing) - Part III

Introduction

Japanese arts began in the Jōmon period (the Japanese neolithic cultural period extending from 8,000 BC to about 200 BC). In ancient times and through rhe middle ages, Japan introduced and subsequently assimilated a superb continental culture: from China and Korea, geographically situated near Japan, and even from far away Persia. In modern times, Japan accepted Western European Culture. These Oriental and Occidental cultures underwent development in this island country of the Far East, resulting in forms of artwork unique to Japan.

This post features selected images from the Idemitsu Museum of Arts which were showcased in an exhibition held at the National Gallery of Victoria on 20 April to 12 June, 1983.

Japanese Colors and Inks on Paper From the Idemitsu Collection[1]

Verdant Mountain in Rain by Aoki Mokubei (1767-1833). Dated 1826.

Technique and Materials: Kakemono; colors on paper.

Size: 133.2 x 28.2 cm.

Comment[1]: Mokubei was best known in his day as a potter. The son of a Kyōto restauranteur, he became a potter after reading a copy of the Tao Shou, the first book on Chinese ceramics, in about 1796. In 1806 he visited the Kutani kilns to help revitalize them. His ceramics are extemely individualistic. He worked in a variety of styles imitating late Ming blue and white, celadons and Kochi wares (the popular name for late Ming Chinese enamel wares used in the tea ceremony), most wares being made for sench, a type of tea drinking that used steeped tea and was much favored by the Japanese Sinophiles as it was less formal than chanoyu.

Mokubei is today more highly regarded for his paintings. He seems to have been self taught and most of his dated works belong to the last twenty years of his life. By the late 18th century nanga was firmly established in the Kyōto-Osaka region, patronised by merchants and rich men. Mokubei's friends included Gyokudō and Chikuden. Chikuden apparently regarded Mokubei as the only true bunjinga after Ike no Taiga.

Rinnasei and Cranes by Tanomura Chikuden (1777-1835). Dated 1830.

Technique and Materials: Kakemono; colors on paper.

Size: 124 x 38.5 cm.

Comment[1]: A painting truly in the Chinese landscape style, nanga, in which the foreground is composed of an idyllic setting with 16th century Chinese poet, Lithe Jing (in Japanese, Rinnasei) seated beneath pine trees quietly contemplating the scene. The cranes, like the pine tree are traditional symbols of longevity, have attracted the interests of a youthful attendant whilst another prepares tea beyond the figure of Linhe Jing. The middle distance is dominated by a towering peak drawn with dry ink brushstrokes which, combined with rock-like forms, give a restless evolving energy to the landscape. Through the valley on the left, distant peaks in light color may be glimpsed. The painting conforms to the traditional Chinese landscape formula of distinct foreground, middle-ground and background elements and the brushwork reflects the tradition of the literati style.

Flowers and Birds by Yamamoto Baiitsu (1783-1856).

Technique and Materials: Kakemono; colors on paper.

Size: 169.3 x 90.1 cm.

Comment[1]: This naturalistic, fresh, elegant painting is typical of the work of Baiitsu who had a particular penchant for bird and flower paintings, inventively portraying the same subject in endless compositional variations. The subject of bird-and-flower painting (kachō-ga) had long been a distinct and esteemed category of both Chinese and Japanese paintings. Baiitsu's handling of ink is delicate and meticulous. His colors are clear. The accuracy of his flowers is a botanist's delight!

The handling of the rocks and ground reflect his literati training. The sensitive and realistic depiction of nature reflects the influence of the Shijō school, while the concept derives ultimately from Chinese later Ming artists such as Zhou Zhimain (active between 1580-1610) who was widely admired in Japan as a specialist in the flowers-and-birds genre.

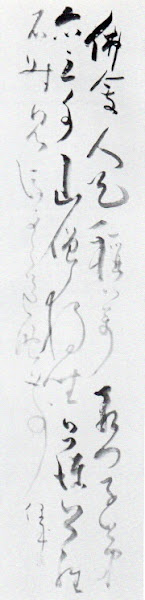

A Quatrain by Sengai Gibon (1750-1837) (1783-1856).

Technique and Materials: Kakemono; ink on paper.

Size: 118.3 x 28.6 cm.

Comment[1]: Sengai was the son of a farmer in Mino (modern Gifu Prefecture). He entered the Seitai-ji temple at Mino at eleven, and at nineteen he started studying under the Zen monk Gessen Zenji at Toki-an, which is near modern Yokohama. Thirteen years later, on the death of Gessen, he moved to the Shōfuku-ji in Hakata, where he eventually became the 123rd abbot (1780-1811). His preist's name was Gibon, so he is usually known as Sengai Gibon. He retired as abbot in 1811, at the age of 61, and nearly all of his paintings and calligraphy was done during the last 25 years of his life. He considered his art an important means of communicating Zen Buddhist values and he is known to have kept busy fulfilling requests for his work.

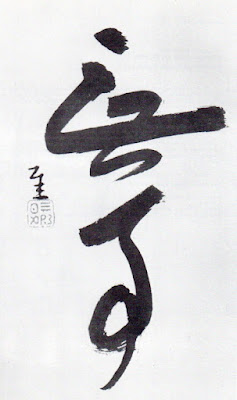

Calligraphy (Buji) by Sengai Gibon (1750-1837).

Technique and Materials: Kakemono; ink on paper.

Size: 36.0 x 21.0 cm.

Comment[1]: Just two characters are written in a strong, quick and abbreviated manner presented with the courage of conviction that the message is important. The two characters read buji in Japanese (or wu-shi in Chinese). As with many concepts expressed in characters, the word does not translate easily into English. Modern dictionaries offer the varying equivalents of "safe", "secure", "peaceful, at leisure". Literally the characters mean "no work" or "no event". Moreover, this calligraphy is an excellent example of the Zen paradox of brevity of execution yet complexity of concept that is at the heart of zenga (Zen painting).

The Autumnal Moon by Sengai Gibon (1750-1837).

Technique and Materials: Kakemono; ink on paper.

Size: 40.6 x 56.9 cm.

Comment[1]: The Zen monks who practice zenga cultivated an unprofessional naivety and spontaniety to their work expressed in the simplest way with as few brush strokes as possible. Often too in zenga, calligraphy and painting have equal importance, and the text and imagery are complementary.

Reference:

[1] J. Menzies and E. Capon, Japan: Masterpieces from the Idemitsu Collection, International Cultural Corporation of Australia Limited, Sydney (1982).

For your convenience, I have listed below other post on Japanese textiles on this blogspot.

Discharge Thundercloud

The Basic Kimono Pattern

The Kimono and Japanese Textile Designs

Traditional Japanese Arabesque Patterns - Part I

Textile Dyeing Patterns of Japan

Traditional Japanese Arabesque Patterns - Part II

Sarasa Arabesque Patterns

Contemporary Japanese Textile Creations

Shibori (Tie-Dying)

History of the Kimono

A Textile Tour of Japan - Part I

A Textile Tour of Japan - Part II

The History of the Obi

Japanese Embroidery (Shishu)

Japanese Dyed Textiles

Aizome (Japanese Indigo Dyeing)

Stencil-Dyed Indigo Arabesque Patterns

Japanese Paintings on Silk

Tsutsugaki - Freehand Paste-Resist Dyeing

Street Play in Tokyo

Birds and Flowers in Japanese Textile Designs

Japanese Colors and Inks on Paper From the Idemitsu Collection

Yuzen: Multicolored Past-Resist Dyeing - Part I

Yuzen: Multi-colored Paste-Resist Dyeing - Part II

Katazome (Stencil Dyeing) - Part I

Katazome (Stencil Dyeing) - Part II

Katazome (Stencil Dyeing) - Part III

Introduction

Japanese arts began in the Jōmon period (the Japanese neolithic cultural period extending from 8,000 BC to about 200 BC). In ancient times and through rhe middle ages, Japan introduced and subsequently assimilated a superb continental culture: from China and Korea, geographically situated near Japan, and even from far away Persia. In modern times, Japan accepted Western European Culture. These Oriental and Occidental cultures underwent development in this island country of the Far East, resulting in forms of artwork unique to Japan.

This post features selected images from the Idemitsu Museum of Arts which were showcased in an exhibition held at the National Gallery of Victoria on 20 April to 12 June, 1983.

Japanese Colors and Inks on Paper From the Idemitsu Collection[1]

Verdant Mountain in Rain by Aoki Mokubei (1767-1833). Dated 1826.

Technique and Materials: Kakemono; colors on paper.

Size: 133.2 x 28.2 cm.

Comment[1]: Mokubei was best known in his day as a potter. The son of a Kyōto restauranteur, he became a potter after reading a copy of the Tao Shou, the first book on Chinese ceramics, in about 1796. In 1806 he visited the Kutani kilns to help revitalize them. His ceramics are extemely individualistic. He worked in a variety of styles imitating late Ming blue and white, celadons and Kochi wares (the popular name for late Ming Chinese enamel wares used in the tea ceremony), most wares being made for sench, a type of tea drinking that used steeped tea and was much favored by the Japanese Sinophiles as it was less formal than chanoyu.

Mokubei is today more highly regarded for his paintings. He seems to have been self taught and most of his dated works belong to the last twenty years of his life. By the late 18th century nanga was firmly established in the Kyōto-Osaka region, patronised by merchants and rich men. Mokubei's friends included Gyokudō and Chikuden. Chikuden apparently regarded Mokubei as the only true bunjinga after Ike no Taiga.

Rinnasei and Cranes by Tanomura Chikuden (1777-1835). Dated 1830.

Technique and Materials: Kakemono; colors on paper.

Size: 124 x 38.5 cm.

Comment[1]: A painting truly in the Chinese landscape style, nanga, in which the foreground is composed of an idyllic setting with 16th century Chinese poet, Lithe Jing (in Japanese, Rinnasei) seated beneath pine trees quietly contemplating the scene. The cranes, like the pine tree are traditional symbols of longevity, have attracted the interests of a youthful attendant whilst another prepares tea beyond the figure of Linhe Jing. The middle distance is dominated by a towering peak drawn with dry ink brushstrokes which, combined with rock-like forms, give a restless evolving energy to the landscape. Through the valley on the left, distant peaks in light color may be glimpsed. The painting conforms to the traditional Chinese landscape formula of distinct foreground, middle-ground and background elements and the brushwork reflects the tradition of the literati style.

Flowers and Birds by Yamamoto Baiitsu (1783-1856).

Technique and Materials: Kakemono; colors on paper.

Size: 169.3 x 90.1 cm.

Comment[1]: This naturalistic, fresh, elegant painting is typical of the work of Baiitsu who had a particular penchant for bird and flower paintings, inventively portraying the same subject in endless compositional variations. The subject of bird-and-flower painting (kachō-ga) had long been a distinct and esteemed category of both Chinese and Japanese paintings. Baiitsu's handling of ink is delicate and meticulous. His colors are clear. The accuracy of his flowers is a botanist's delight!

The handling of the rocks and ground reflect his literati training. The sensitive and realistic depiction of nature reflects the influence of the Shijō school, while the concept derives ultimately from Chinese later Ming artists such as Zhou Zhimain (active between 1580-1610) who was widely admired in Japan as a specialist in the flowers-and-birds genre.

A Quatrain by Sengai Gibon (1750-1837) (1783-1856).

Technique and Materials: Kakemono; ink on paper.

Size: 118.3 x 28.6 cm.

Comment[1]: Sengai was the son of a farmer in Mino (modern Gifu Prefecture). He entered the Seitai-ji temple at Mino at eleven, and at nineteen he started studying under the Zen monk Gessen Zenji at Toki-an, which is near modern Yokohama. Thirteen years later, on the death of Gessen, he moved to the Shōfuku-ji in Hakata, where he eventually became the 123rd abbot (1780-1811). His preist's name was Gibon, so he is usually known as Sengai Gibon. He retired as abbot in 1811, at the age of 61, and nearly all of his paintings and calligraphy was done during the last 25 years of his life. He considered his art an important means of communicating Zen Buddhist values and he is known to have kept busy fulfilling requests for his work.

Calligraphy (Buji) by Sengai Gibon (1750-1837).

Technique and Materials: Kakemono; ink on paper.

Size: 36.0 x 21.0 cm.

Comment[1]: Just two characters are written in a strong, quick and abbreviated manner presented with the courage of conviction that the message is important. The two characters read buji in Japanese (or wu-shi in Chinese). As with many concepts expressed in characters, the word does not translate easily into English. Modern dictionaries offer the varying equivalents of "safe", "secure", "peaceful, at leisure". Literally the characters mean "no work" or "no event". Moreover, this calligraphy is an excellent example of the Zen paradox of brevity of execution yet complexity of concept that is at the heart of zenga (Zen painting).

The Autumnal Moon by Sengai Gibon (1750-1837).

Technique and Materials: Kakemono; ink on paper.

Size: 40.6 x 56.9 cm.

Comment[1]: The Zen monks who practice zenga cultivated an unprofessional naivety and spontaniety to their work expressed in the simplest way with as few brush strokes as possible. Often too in zenga, calligraphy and painting have equal importance, and the text and imagery are complementary.

Reference:

[1] J. Menzies and E. Capon, Japan: Masterpieces from the Idemitsu Collection, International Cultural Corporation of Australia Limited, Sydney (1982).

No comments:

Post a Comment