Preamble

This is the thirtieth post in a new Art Resource series that specifically focuses on techniques used in creating artworks. For your convenience I have listed all the posts in this new series below:

Drawing Art

Painting Art - Part I

Painting Art - Part II

Painting Art - Part III

Painting Art - Part IV

Painting Art - Part V

Painting Art - Part VI

Home-Made Painting Art Materials

Quality in Ready-Made Artists' Supplies - Part I

Quality in Ready-Made Artists' Supplies - Part II

Quality in Ready-Made Artists' Supplies - Part III

Historical Notes on Art - Part I

Historical Notes on Art - Part II

Historical Notes on Art - Part III

Historical Notes on Art - Part IV

Historical Notes on Art - Part V

Tempera Painting

Oil Painting - Part I

Oil Painting - Part II

Oil Painting - Part III

Oil Painting - Part IV

Oil Painting - Part V

Oil Painting - Part VI

Pigments

Classification of Pigments - Part I

Classification of Pigments - Part II

Classification of Pigments - Part III

Pigments for Oil Painting

Pigments for Water Color

Pigments for Tempera Painting

Pigments for Pastel

Japanese Pigments

Pigments for Fresco Painting - Part I

Pigments for Fresco Painting - Part II

Selected Fresco Palette for Permanent Frescoes

Properties of Pigments in Common Use

Blue Pigments - Part I

Blue Pigments - Part II

Blue Pigments - Part III

Green Pigments - Part I

Green Pigments - Part II

Red Pigments - Part I

Red Pigments - Part II

Yellow Pigments - Part I

Yellow Pigments - Part II

Brown and Violet Pigments

Black Pigments

White Pigments - Part I

White Pigments - Part II

White Pigments - Part III

Inert Pigments

There have been another one hundred and thirteen posts in a previous Art Resource series that have focused on the following topics:

(i) Units used in dyeing and printing of fabrics;

(ii) Occupational, health & safety issues in an art studio;

(iii) Color theories and color schemes;

(iv) Optical properties of fiber materials;

(v) General properties of fiber polymers and fibers - Part I to Part V;

(vi) Protein fibers;

(vii) Natural and man-made cellulosic fibers;

(viii) Fiber blends and melt spun fibers;

(ix) Fabric construction;

(x) Techniques and woven fibers;

(xi) Basic and figured weaves;

(xii) Pile, woven and knot pile fabrics;

(xiii) Durable press and wash-and-wear finishes;

(xvi) Classification of dyes and dye blends;

(xv) The general theory of printing.

To access any of the above resources, please click on the following link - Units Used in Dyeing and Printing of Fabrics. This link will highlight all of the one hundred and thirteen posts in the previous a are eight data bases on this blogspot, namely, the Glossary of Cultural and Architectural Terms, Timelines of Fabrics, Dyes and Other Stuff, A Fashion Data Base, the Glossary of Colors, Dyes, Inks, Pigments and Resins, the Glossary of Fabrics, Fibers, Finishes, Garments and Yarns, Glossary of Art, Artists, Art Motifs and Art Movements, Glossary of Paper, Photography, Printing, Prints and Publication Terms and the Glossary of Scientific Terms. All data bases in the future will be updated from time-to-time.

If you find any post on this blog site useful, you can save it or copy and paste it into your own "Word" document for your future reference. For example, Safari allows you to save a post (e.g. click on "File", click on "Print" and release, click on "PDF" and then click on "Save As" and release - and a PDF should appear where you have stored it). Safari also allows you to mail a post to a friend (click on "File", and then point cursor to "Mail Contents On This Page" and release). Either way, this or other posts on this site may be a useful Art Resource for you.

The new Art Resource series will be the first post in each calendar month. Remember - these Art Resource posts span information that will be useful for a home hobbyist to that required by a final year University Fine-Art student and so undoubtedly, some parts of any Art Resource post may appear far too technical for your needs (skip those mind boggling parts) and in other parts, it may be too simplistic with respect to your level of knowledge (ditto the skip). The trade-off between these two extremes will mean that Art Resource posts will be hopefully useful in parts to most, but unfortunately may not be satisfying to all!

Introduction

Tempera painting, is painting executed with pigment ground in a water-miscible medium. The word 'tempera' originally came from the verb 'temper'; that is, to bring to a desired consistency. Dry pigments are made usable by 'tempering' them with a binding and adhesive vehicle. Such painting was distinguished from fresco painting, as the colors contained no binder. Eventually, after the rise of oil painting, the word gained its present meaning.

Tempera is an ancient medium, having been in constant use in most of the world’s cultures until it was gradually superseded by oil paints in Europe, during the Renaissance. Tempera was the original mural medium in the ancient dynasties of Egypt, Babylonia, Mycenaean Greece, and China and was used to decorate the early Christian catacombs. It was employed on a variety of supports, from the stone stelae (or commemorative pillars), mummy cases, and papyrus rolls of ancient Egypt to the wood panels of Byzantine icons and altarpieces and the vellum leaves of medieval illuminated manuscripts.

Artist and Title: William Blake (1757–1827). Lot and His Daughters (1799–1800).

Technique: Pen and tempera on canvas.

Size: 10 1/4 x 14 3/4 in. (26 x 37.5 cm).

Courtesy: The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens

True tempera is made by a mixture containing the yolk of fresh eggs, although manuscript illuminators often used egg white and some easel painters added the whole egg. Other emulsions—such as casein glue with linseed oil, egg yolk with gum and linseed oil, and egg white with linseed or poppy oil—have also been used. Individual painters have experimented with other recipes, but few of those have proved successful; all but William Blake’s later tempera paintings on copper sheets, for instance, have darkened and decayed, and it is thought that he mixed his pigment with carpenter’s glue.

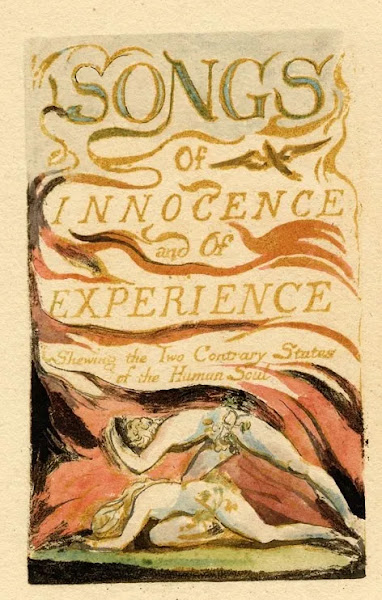

Artist and Title: William Blake (1757–1827) Songs of Innocence and of Experience (1794).

Technique: Hand-colored relief etching on copper plate.

Size: 112 x 68 mm.

Courtesy: Print Room, The British Museum.

Distemper is a crude form of tempera made by mixing dry pigment into a paste with water, which is thinned with heated glue in working or by adding pigment to whiting (a mixture of fine-ground chalk and size). It is used for stage scenery and full-size preparatory cartoons for murals and tapestries. When dry, its colors have the pale, matte, powdery quality of pastels, with a similar tendency to smudge. Indeed, damaged cartoons have been retouched with pastel chalks.

Artist and Title: Dirk Bouts, The Entombment (Graflegging in Dutch), probably 1450s.

Technique: Glue-size tempera on linen.

Size: 87.5 × 73.6 cm (34.4 × 29 in).

Courtesy: National Gallery, London (NG 664).

Egg tempera is the most-durable form of the medium, being generally unaffected by humidity and temperature. It dries quickly to form a tough film that acts as a protective skin to the support. In handling, in its diversity of transparent and opaque effects, and in the satin sheen of its finish, it resembles the modern acrylic resin emulsion paints.

Artist: Duccio di Buoninsegna (ca. 1283-1284).

Technique and Materials: Tempera and gold on wood.

Size: 86 cm × 60 cm (34 in × 24 in).

Courtesy: Museo dell'Opera metropolitana del Duomo, Siena.

Traditional tempera painting is a lengthy process. Its supports are smooth surfaces, such as planed wood, fine set plaster, stone, paper, vellum, canvas, and modern composition boards of compressed wood or paper. Linen is generally glued to the surface of panel supports, additional strips masking the seams between braced wood planks. Gesso, a mixture of plaster of paris (or gypsum) with size, is the traditional ground. The first layer is of gesso grosso, a mixture of coarse unslaked plaster and size. That provides a rough absorbent surface for 10 or more thin coats of gesso sottile, a smooth mixture of size and fine plaster previously slaked in water to retard drying. This laborious preparation results in an opaque, brilliant white, light-reflecting surface similar in texture to hard flat icing sugar.

The design for a large tempera painting was traditionally executed in distemper on a thick paper cartoon. The outlines were pricked with a perforating wheel so that when the cartoon was laid on the surface of the support, the linear pattern was transferred by dabbing, or “pouncing,” the perforations with a muslin bag of powdered charcoal. The dotted contours traced through were then fixed in paint. Medieval tempera painters of panels and manuscripts made lavish use of gold leaf on backgrounds and for symbolic features, such as haloes and beams of heavenly light. Areas of the pounced design intended for gilding were first built up into low relief with gesso duro, the harder, less-absorbent gesso compound also used for elaborate frame moldings. Background fields were often textured by impressing the gesso duro, before it set, with small, carved, intaglio wood blocks to create raised, pimpled, and quilted repeat patterns that glittered when gilded. Leaves of finely beaten gold were pressed onto a tacky mordant (adhesive compound) or over wet bole (reddish brown earth pigment) that gave greater warmth and depth when the gilded areas were burnished.

Colors were applied with sable brushes in successive broad sweeps or washes of semi-transparent tempera. Those dried quickly, preventing the subtle tonal gradations possible with watercolor washes or oil paint; effects of shaded modelling therefore had to be obtained by a crosshatching technique of fine brush strokes. According to the Italian painter Cennino Cennini, the early Renaissance tempera painters laid the color washes across a fully modeled monochrome underpainting in terre vert (olive-green pigment), a method later developed into the mixed mediums technique of tempera underpainting followed by transparent oil glazes.

The luminous gesso base of a tempera painting, combined with the cumulative effect of overlaid color washes, produces a unique depth and intensity of color. Tempera paints dry lighter in value, but their original tonality can be restored by subsequent waxing or varnishing. Other characteristic qualities of a tempera painting, resulting from its fast-drying property and disciplined technique, are its steely lines and crisp edges, its meticulous detail and rich linear textures, and its overall emphasis upon a decorative flat pattern of bold color masses.

Pigments for Tempera Painting

The list of pigments for tempera painting is the same as that for oil painting except that no pigments containing lead may be used if the painting is to be completely tempera without oil or varnish glazes. When it is to be thouroughly varnished or glazed and varnished, flake white and Naples yellow may be used.

Flake White.

Naples Yellow.

In most tempera mediums, titanium has better brushing qualities than either lead or zinc, and it displays none of the faults that it sometimes may exhibit in oil. The extremely powerful tinting strength of the pure oxide is sometimes awkward, and in most instances the barium composite variety will be preferable. The titanium pigments replace white lead in tempera more statisfactorily than they do in oil.

There are no chemical restrictions as to the various permanent colors which may or may not be used in underpaintings, as even when oil is a constituent of a correctly balnced emulsion, the variation in the flexibility of the films due to a variation in oil absorption by pigments is negligible. The remarks on colors for glazing oil paintings are applicable to colors for glazing tempera.

Reference:

[1] The Artist's Handbook of Materials and Techniques, R. Mayer (ed. E. Smith) 4th Edition, Faber and Faber, London (1981).

This is the thirtieth post in a new Art Resource series that specifically focuses on techniques used in creating artworks. For your convenience I have listed all the posts in this new series below:

Drawing Art

Painting Art - Part I

Painting Art - Part II

Painting Art - Part III

Painting Art - Part IV

Painting Art - Part V

Painting Art - Part VI

Home-Made Painting Art Materials

Quality in Ready-Made Artists' Supplies - Part I

Quality in Ready-Made Artists' Supplies - Part II

Quality in Ready-Made Artists' Supplies - Part III

Historical Notes on Art - Part I

Historical Notes on Art - Part II

Historical Notes on Art - Part III

Historical Notes on Art - Part IV

Historical Notes on Art - Part V

Tempera Painting

Oil Painting - Part I

Oil Painting - Part II

Oil Painting - Part III

Oil Painting - Part IV

Oil Painting - Part V

Oil Painting - Part VI

Pigments

Classification of Pigments - Part I

Classification of Pigments - Part II

Classification of Pigments - Part III

Pigments for Oil Painting

Pigments for Water Color

Pigments for Tempera Painting

Pigments for Pastel

Japanese Pigments

Pigments for Fresco Painting - Part I

Pigments for Fresco Painting - Part II

Selected Fresco Palette for Permanent Frescoes

Properties of Pigments in Common Use

Blue Pigments - Part I

Blue Pigments - Part II

Blue Pigments - Part III

Green Pigments - Part I

Green Pigments - Part II

Red Pigments - Part I

Red Pigments - Part II

Yellow Pigments - Part I

Yellow Pigments - Part II

Brown and Violet Pigments

Black Pigments

White Pigments - Part I

White Pigments - Part II

White Pigments - Part III

Inert Pigments

There have been another one hundred and thirteen posts in a previous Art Resource series that have focused on the following topics:

(i) Units used in dyeing and printing of fabrics;

(ii) Occupational, health & safety issues in an art studio;

(iii) Color theories and color schemes;

(iv) Optical properties of fiber materials;

(v) General properties of fiber polymers and fibers - Part I to Part V;

(vi) Protein fibers;

(vii) Natural and man-made cellulosic fibers;

(viii) Fiber blends and melt spun fibers;

(ix) Fabric construction;

(x) Techniques and woven fibers;

(xi) Basic and figured weaves;

(xii) Pile, woven and knot pile fabrics;

(xiii) Durable press and wash-and-wear finishes;

(xvi) Classification of dyes and dye blends;

(xv) The general theory of printing.

To access any of the above resources, please click on the following link - Units Used in Dyeing and Printing of Fabrics. This link will highlight all of the one hundred and thirteen posts in the previous a are eight data bases on this blogspot, namely, the Glossary of Cultural and Architectural Terms, Timelines of Fabrics, Dyes and Other Stuff, A Fashion Data Base, the Glossary of Colors, Dyes, Inks, Pigments and Resins, the Glossary of Fabrics, Fibers, Finishes, Garments and Yarns, Glossary of Art, Artists, Art Motifs and Art Movements, Glossary of Paper, Photography, Printing, Prints and Publication Terms and the Glossary of Scientific Terms. All data bases in the future will be updated from time-to-time.

If you find any post on this blog site useful, you can save it or copy and paste it into your own "Word" document for your future reference. For example, Safari allows you to save a post (e.g. click on "File", click on "Print" and release, click on "PDF" and then click on "Save As" and release - and a PDF should appear where you have stored it). Safari also allows you to mail a post to a friend (click on "File", and then point cursor to "Mail Contents On This Page" and release). Either way, this or other posts on this site may be a useful Art Resource for you.

The new Art Resource series will be the first post in each calendar month. Remember - these Art Resource posts span information that will be useful for a home hobbyist to that required by a final year University Fine-Art student and so undoubtedly, some parts of any Art Resource post may appear far too technical for your needs (skip those mind boggling parts) and in other parts, it may be too simplistic with respect to your level of knowledge (ditto the skip). The trade-off between these two extremes will mean that Art Resource posts will be hopefully useful in parts to most, but unfortunately may not be satisfying to all!

Introduction

Tempera painting, is painting executed with pigment ground in a water-miscible medium. The word 'tempera' originally came from the verb 'temper'; that is, to bring to a desired consistency. Dry pigments are made usable by 'tempering' them with a binding and adhesive vehicle. Such painting was distinguished from fresco painting, as the colors contained no binder. Eventually, after the rise of oil painting, the word gained its present meaning.

Tempera is an ancient medium, having been in constant use in most of the world’s cultures until it was gradually superseded by oil paints in Europe, during the Renaissance. Tempera was the original mural medium in the ancient dynasties of Egypt, Babylonia, Mycenaean Greece, and China and was used to decorate the early Christian catacombs. It was employed on a variety of supports, from the stone stelae (or commemorative pillars), mummy cases, and papyrus rolls of ancient Egypt to the wood panels of Byzantine icons and altarpieces and the vellum leaves of medieval illuminated manuscripts.

Artist and Title: William Blake (1757–1827). Lot and His Daughters (1799–1800).

Technique: Pen and tempera on canvas.

Size: 10 1/4 x 14 3/4 in. (26 x 37.5 cm).

Courtesy: The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens

True tempera is made by a mixture containing the yolk of fresh eggs, although manuscript illuminators often used egg white and some easel painters added the whole egg. Other emulsions—such as casein glue with linseed oil, egg yolk with gum and linseed oil, and egg white with linseed or poppy oil—have also been used. Individual painters have experimented with other recipes, but few of those have proved successful; all but William Blake’s later tempera paintings on copper sheets, for instance, have darkened and decayed, and it is thought that he mixed his pigment with carpenter’s glue.

Artist and Title: William Blake (1757–1827) Songs of Innocence and of Experience (1794).

Technique: Hand-colored relief etching on copper plate.

Size: 112 x 68 mm.

Courtesy: Print Room, The British Museum.

Distemper is a crude form of tempera made by mixing dry pigment into a paste with water, which is thinned with heated glue in working or by adding pigment to whiting (a mixture of fine-ground chalk and size). It is used for stage scenery and full-size preparatory cartoons for murals and tapestries. When dry, its colors have the pale, matte, powdery quality of pastels, with a similar tendency to smudge. Indeed, damaged cartoons have been retouched with pastel chalks.

Artist and Title: Dirk Bouts, The Entombment (Graflegging in Dutch), probably 1450s.

Technique: Glue-size tempera on linen.

Size: 87.5 × 73.6 cm (34.4 × 29 in).

Courtesy: National Gallery, London (NG 664).

Egg tempera is the most-durable form of the medium, being generally unaffected by humidity and temperature. It dries quickly to form a tough film that acts as a protective skin to the support. In handling, in its diversity of transparent and opaque effects, and in the satin sheen of its finish, it resembles the modern acrylic resin emulsion paints.

Artist: Duccio di Buoninsegna (ca. 1283-1284).

Technique and Materials: Tempera and gold on wood.

Size: 86 cm × 60 cm (34 in × 24 in).

Courtesy: Museo dell'Opera metropolitana del Duomo, Siena.

Traditional tempera painting is a lengthy process. Its supports are smooth surfaces, such as planed wood, fine set plaster, stone, paper, vellum, canvas, and modern composition boards of compressed wood or paper. Linen is generally glued to the surface of panel supports, additional strips masking the seams between braced wood planks. Gesso, a mixture of plaster of paris (or gypsum) with size, is the traditional ground. The first layer is of gesso grosso, a mixture of coarse unslaked plaster and size. That provides a rough absorbent surface for 10 or more thin coats of gesso sottile, a smooth mixture of size and fine plaster previously slaked in water to retard drying. This laborious preparation results in an opaque, brilliant white, light-reflecting surface similar in texture to hard flat icing sugar.

The design for a large tempera painting was traditionally executed in distemper on a thick paper cartoon. The outlines were pricked with a perforating wheel so that when the cartoon was laid on the surface of the support, the linear pattern was transferred by dabbing, or “pouncing,” the perforations with a muslin bag of powdered charcoal. The dotted contours traced through were then fixed in paint. Medieval tempera painters of panels and manuscripts made lavish use of gold leaf on backgrounds and for symbolic features, such as haloes and beams of heavenly light. Areas of the pounced design intended for gilding were first built up into low relief with gesso duro, the harder, less-absorbent gesso compound also used for elaborate frame moldings. Background fields were often textured by impressing the gesso duro, before it set, with small, carved, intaglio wood blocks to create raised, pimpled, and quilted repeat patterns that glittered when gilded. Leaves of finely beaten gold were pressed onto a tacky mordant (adhesive compound) or over wet bole (reddish brown earth pigment) that gave greater warmth and depth when the gilded areas were burnished.

Colors were applied with sable brushes in successive broad sweeps or washes of semi-transparent tempera. Those dried quickly, preventing the subtle tonal gradations possible with watercolor washes or oil paint; effects of shaded modelling therefore had to be obtained by a crosshatching technique of fine brush strokes. According to the Italian painter Cennino Cennini, the early Renaissance tempera painters laid the color washes across a fully modeled monochrome underpainting in terre vert (olive-green pigment), a method later developed into the mixed mediums technique of tempera underpainting followed by transparent oil glazes.

The luminous gesso base of a tempera painting, combined with the cumulative effect of overlaid color washes, produces a unique depth and intensity of color. Tempera paints dry lighter in value, but their original tonality can be restored by subsequent waxing or varnishing. Other characteristic qualities of a tempera painting, resulting from its fast-drying property and disciplined technique, are its steely lines and crisp edges, its meticulous detail and rich linear textures, and its overall emphasis upon a decorative flat pattern of bold color masses.

Pigments for Tempera Painting

The list of pigments for tempera painting is the same as that for oil painting except that no pigments containing lead may be used if the painting is to be completely tempera without oil or varnish glazes. When it is to be thouroughly varnished or glazed and varnished, flake white and Naples yellow may be used.

Flake White.

Naples Yellow.

In most tempera mediums, titanium has better brushing qualities than either lead or zinc, and it displays none of the faults that it sometimes may exhibit in oil. The extremely powerful tinting strength of the pure oxide is sometimes awkward, and in most instances the barium composite variety will be preferable. The titanium pigments replace white lead in tempera more statisfactorily than they do in oil.

There are no chemical restrictions as to the various permanent colors which may or may not be used in underpaintings, as even when oil is a constituent of a correctly balnced emulsion, the variation in the flexibility of the films due to a variation in oil absorption by pigments is negligible. The remarks on colors for glazing oil paintings are applicable to colors for glazing tempera.

Reference:

[1] The Artist's Handbook of Materials and Techniques, R. Mayer (ed. E. Smith) 4th Edition, Faber and Faber, London (1981).

No comments:

Post a Comment