Preamble

This is the seventeenth post in a new Art Resource series that specifically focuses on techniques used in creating artworks. For your convenience I have listed all the posts in this new series below:

Drawing Art

Painting Art - Part I

Painting Art - Part II

Painting Art - Part III

Painting Art - Part IV

Painting Art - Part V

Painting Art - Part VI

Home-Made Painting Art Materials

Quality in Ready-Made Artists' Supplies - Part I

Quality in Ready-Made Artists' Supplies - Part II

Quality in Ready-Made Artists' Supplies - Part III

Historical Notes on Art - Part I

Historical Notes on Art - Part II

Historical Notes on Art - Part III

Historical Notes on Art - Part IV

Historical Notes on Art - Part V

Tempera Painting

Oil Painting - Part I

Oil Painting - Part II

Oil Painting - Part III

Oil Painting - Part IV

Oil Painting - Part V

Oil Painting - Part VI

Pigments

Classification of Pigments - Part I

Classification of Pigments - Part II

Classification of Pigments - Part III

Pigments for Oil Painting

Pigments for Water Color

Pigments for Tempera Painting

Pigments for Pastel

Japanese Pigments

Pigments for Fresco Painting - Part I

Pigments for Fresco Painting - Part II

Selected Fresco Palette for Permanent Frescoes

Properties of Pigments in Common Use

Blue Pigments - Part I

Blue Pigments - Part II

Blue Pigments - Part III

Green Pigments - Part I

Green Pigments - Part II

Red Pigments - Part I

Red Pigments - Part II

Yellow Pigments - Part I

Yellow Pigments - Part II

Brown and Violet Pigments

Black Pigments

White Pigments - Part I

White Pigments - Part II

White Pigments - Part III

Inert Pigments

Permanence of Pigments: New Pigments - Part I

Permanence of Pigments: New Pigments - Part II

There have been another one hundred and thirteen posts in a previous Art Resource series that have focused on the following topics:

(i) Units used in dyeing and printing of fabrics;

(ii) Occupational, health & safety issues in an art studio;

(iii) Color theories and color schemes;

(iv) Optical properties of fiber materials;

(v) General properties of fiber polymers and fibers - Part I to Part V;

(vi) Protein fibers;

(vii) Natural and man-made cellulosic fibers;

(viii) Fiber blends and melt spun fibers;

(ix) Fabric construction;

(x) Techniques and woven fibers;

(xi) Basic and figured weaves;

(xii) Pile, woven and knot pile fabrics;

(xiii) Nainkage, durable press and wash-wear finishes;

(xvi) Classification of dyes and dye blends;

(xv) The general theory of printing.

To access any of the above resources, please click on the following link - Units Used in Dyeing and Printing of Fabrics. This link will highlight all of the one hundred and thirteen posts in the previous a are eight data bases on this blogspot, namely, the Glossary of Cultural and Architectural Terms, Timelines of Fabrics, Dyes and Other Stuff, A Fashion Data Base, the Glossary of Colors, Dyes, Inks, Pigments and Resins, the Glossary of Fabrics, Fibers, Finishes, Garments and Yarns, Glossary of Art, Artists, Art Motifs and Art Movements, Glossary of Paper, Photography, Printing, Prints and Publication Terms and the Glossary of Scientific Terms. All data bases in the future will be updated from time-to-time.

If you find any post on this blog site useful, you can save it or copy and paste it into your own "Word" document for your future reference. For example, Safari allows you to save a post (e.g. click on "File", click on "Print" and release, click on "PDF" and then click on "Save As" and release - and a PDF should appear where you have stored it). Safari also allows you to mail a post to a friend (click on "File", and then point cursor to "Mail Contents On This Page" and release). Either way, this or other posts on this site may be a useful Art Resource for you.

The new Art Resource series will be the first post in each calendar month. Remember - these Art Resource posts span information that will be useful for a home hobbyist to that required by a final year University Fine-Art student and so undoubtedly, some parts of any Art Resource post may appear far too technical for your needs (skip those mind boggling parts) and in other parts, it may be too simplistic with respect to your level of knowledge (ditto the skip). The trade-off between these two extremes will mean that Art Resource posts will be hopefully useful in parts to most, but unfortunately may not be satisfying to all!

Tempera Painting[1]

From the crude beginnings in Byzantine and early Christian art and, as some early writers suggest, but without definite proof, from the ancient Greeks, a traditional tempera process came into general use throughout Italy.

Egg Tempera process.

The pure egg-yolk technique was described by Cennino Cennini in a treatise on painting as practiced at least as early as the fourteenth century; it was well established in his day, and his knowledge and training using this technique came to him from the studio of his idol, Giotto.

Giotto 1267-1337.

Egg tempera continued to be the principal medium used for easle painting in Europe until the development of artistic oil painting. As the art expert Eastlake expresses it, the early Italian painters, though taking great care to produce durable works, made no attempt to lessen executive difficulties tending rather to overcome such difficulties by superior skill.

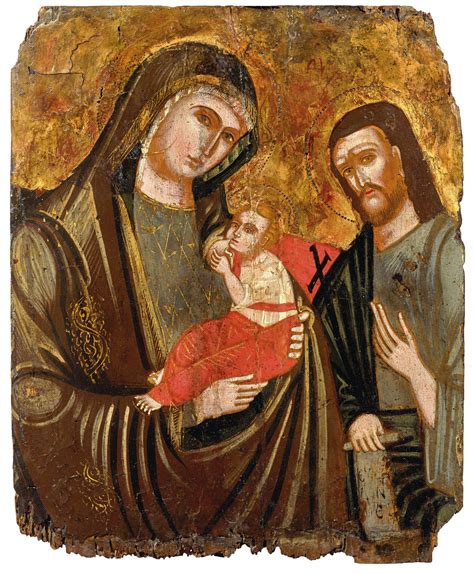

Madonna and Child by Duccio. Tempera with gold ground on wood, 1284, Siena.

The Flemish and other Northern painters departed from the early Italian methods, using new materials, aimed at ease of manipulation, and producing works technically excellent to a degree impossible to duplicate by strict adherence to the egg tempera technique of Cennini.These methods and materials are supposed to have been initiated about the year 1400 in Flanders and thereafter introduced into Venice.

Figure above shows a map of Europe in the fifteenth century. The area in Northern Europe that is dark red is Flanders, which was controlled by the Dukes of Burgundy (in France) during this time period. We now call the art and culture of this area, Flemish.

Though the medium of oil paint had been in use since the late middle ages, the artists of the North were the first to exploit what this medium had to offer. Using thin layers of paint, called glazes, they created a depth of color that was entirely new, and because oil paint can imitate textures far better than fresco or tempera, it was perfectly suited to creating that illusion of reality that was so important to Renaissance artists and patrons. In contrast to oil paint, tempera dries quickly and to create an illusion of three dimensional form, the paint has to be applied in short thin brushstrokes, like cross-hatching. In the Northern Renaissance, we see artists making the most of oil paint—creating the illusion of light reflecting on metal surfaces or jewels, and textures that appear to replicate real fur, hair, wool or wood.

The period from the beginning of the fifteenth century to about the middle of the sixteenth century produced tempera paintings of a high degree of technical excellence, which serve as models for the tempera techniques of today.

The Holy Family.

Tempera on panel, 39 x 32 cm, unframed.

Around the same time (beginning about 1400 AD) new materials began to be discovered or perfected. A commercial renaissance began, a result of which was the wide distribution and availability of raw materials. Traders brought supplies from the Orient, and the manufacture of finished goods on a larger scale improved quality and gave uniformity to materials in common use.

Linseed oil had been known and used for ordinary decorative and protective coatings from the earliest recorded periods of European history, but it was a crude, mucilaginous product unlike well-made material we know now as raw linseed oil; however, thinners such a turpentine were virtually unknown. Processes for the purification of linseed oil in the modern sense began to be published about the year, that is 1400.

Distillation was known to writers of the third century AD, but it was not practiced commercially until the fifteenth century, at which time its products, alcohol and other volatile solvents for varnishes and paints, began to be widely available.

The process of alkali refining linseed oil.

The aim and taste of the artists and their public should be taken into consideration when a study of these changes in techniques is made. Vasari and other writers who lived in a day when tempera was becoming obsolete, and when novel effects produced by oils were widely acclaimed were often prone to condemn the tempera technique from the viewpoint of the tastes, fashions, and styles of their day. Tempera painting was condemned by them as inferior to oil because of the very qualities which make it appeal to its present-day users.

Fred Wessel's tempera painting. He is a professor of printmaking at the Hartford Art School at University of Hartford in Connecticut. He teaches tempera painting, lithography and drawing. Fred did his BFA at Syracuse University in New York and MFA at the University of Massachusetts He is very much inclined towards Italian Renaissance and takes his inspiration from the same. He says: "The ever-changing inner light that radiates from gold leaf used judiciously on the surface of a painting, and the use of pockets of rich, intense colors that illuminate the picture's surface impressed me deeply".

During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, some tempera paintings were done on canvas, which had been introduced with the oil painting technique, by that time in full swing. Tempera as a universally used medium in a high state of technical development may be considered to have become obsolete by the end of the sixteenth century.

In following any recipes or instructions of former times, even up to nineteenth-century methods, it is important to remember that the quality, character, and nomenclature of many raw materials have undergone changes, and to be familiar with the artistic or pictorial aims of the period for which the methods were intended.

The statement, made in accordance with general opinion, that tempera painting became obsolete more than three hundred years prior to its present revival, is true only so far as its wide general usage is concerned. Examples and records of isolated works done with older materials can be cited for almost every age, but these individual experiments had small influence either on the general practice among painters of the time or on the major part of the painters' own works. The present revival of tempera owes its extent to the adaption of the technique to the requirements of modern taste, since it makes possible effects particularly well suited to certain modern artistic aims, which did not exist in the recent past. In the early part of the 20th Century its seems to have received its greatest impetus in Germany, although isolated groups of English and American painters have also pioneered its use.

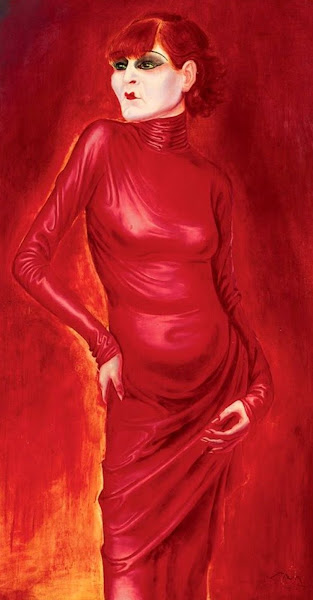

Title and Artist: The Dancer Anita Berber by Otto Dix (German).

Techniques and Materials: oil and tempera on plywood.

Some partial use of tempera by American painters of the early nineteenth century is recorded. Scully recommended that colors be ground in skim milk (crude casein). A ground made from skim milk and white lead was one of his favorites, and he also mentioned the use of colors ground in skim milk for underpaintings, carrying this work as far towards completion as possible, then finishing with transparent oil and varnish glazes. An emulsion of flour paste and Venice turpentine is also mentioned.

Reference:

[1] The Artist's Handbook of Materials and Techniques, R. Mayer, (ed. E. Smith) 4th Edition, Faber and Faber, London (1981).

This is the seventeenth post in a new Art Resource series that specifically focuses on techniques used in creating artworks. For your convenience I have listed all the posts in this new series below:

Drawing Art

Painting Art - Part I

Painting Art - Part II

Painting Art - Part III

Painting Art - Part IV

Painting Art - Part V

Painting Art - Part VI

Home-Made Painting Art Materials

Quality in Ready-Made Artists' Supplies - Part I

Quality in Ready-Made Artists' Supplies - Part II

Quality in Ready-Made Artists' Supplies - Part III

Historical Notes on Art - Part I

Historical Notes on Art - Part II

Historical Notes on Art - Part III

Historical Notes on Art - Part IV

Historical Notes on Art - Part V

Tempera Painting

Oil Painting - Part I

Oil Painting - Part II

Oil Painting - Part III

Oil Painting - Part IV

Oil Painting - Part V

Oil Painting - Part VI

Pigments

Classification of Pigments - Part I

Classification of Pigments - Part II

Classification of Pigments - Part III

Pigments for Oil Painting

Pigments for Water Color

Pigments for Tempera Painting

Pigments for Pastel

Japanese Pigments

Pigments for Fresco Painting - Part I

Pigments for Fresco Painting - Part II

Selected Fresco Palette for Permanent Frescoes

Properties of Pigments in Common Use

Blue Pigments - Part I

Blue Pigments - Part II

Blue Pigments - Part III

Green Pigments - Part I

Green Pigments - Part II

Red Pigments - Part I

Red Pigments - Part II

Yellow Pigments - Part I

Yellow Pigments - Part II

Brown and Violet Pigments

Black Pigments

White Pigments - Part I

White Pigments - Part II

White Pigments - Part III

Inert Pigments

Permanence of Pigments: New Pigments - Part I

Permanence of Pigments: New Pigments - Part II

There have been another one hundred and thirteen posts in a previous Art Resource series that have focused on the following topics:

(i) Units used in dyeing and printing of fabrics;

(ii) Occupational, health & safety issues in an art studio;

(iii) Color theories and color schemes;

(iv) Optical properties of fiber materials;

(v) General properties of fiber polymers and fibers - Part I to Part V;

(vi) Protein fibers;

(vii) Natural and man-made cellulosic fibers;

(viii) Fiber blends and melt spun fibers;

(ix) Fabric construction;

(x) Techniques and woven fibers;

(xi) Basic and figured weaves;

(xii) Pile, woven and knot pile fabrics;

(xiii) Nainkage, durable press and wash-wear finishes;

(xvi) Classification of dyes and dye blends;

(xv) The general theory of printing.

To access any of the above resources, please click on the following link - Units Used in Dyeing and Printing of Fabrics. This link will highlight all of the one hundred and thirteen posts in the previous a are eight data bases on this blogspot, namely, the Glossary of Cultural and Architectural Terms, Timelines of Fabrics, Dyes and Other Stuff, A Fashion Data Base, the Glossary of Colors, Dyes, Inks, Pigments and Resins, the Glossary of Fabrics, Fibers, Finishes, Garments and Yarns, Glossary of Art, Artists, Art Motifs and Art Movements, Glossary of Paper, Photography, Printing, Prints and Publication Terms and the Glossary of Scientific Terms. All data bases in the future will be updated from time-to-time.

If you find any post on this blog site useful, you can save it or copy and paste it into your own "Word" document for your future reference. For example, Safari allows you to save a post (e.g. click on "File", click on "Print" and release, click on "PDF" and then click on "Save As" and release - and a PDF should appear where you have stored it). Safari also allows you to mail a post to a friend (click on "File", and then point cursor to "Mail Contents On This Page" and release). Either way, this or other posts on this site may be a useful Art Resource for you.

The new Art Resource series will be the first post in each calendar month. Remember - these Art Resource posts span information that will be useful for a home hobbyist to that required by a final year University Fine-Art student and so undoubtedly, some parts of any Art Resource post may appear far too technical for your needs (skip those mind boggling parts) and in other parts, it may be too simplistic with respect to your level of knowledge (ditto the skip). The trade-off between these two extremes will mean that Art Resource posts will be hopefully useful in parts to most, but unfortunately may not be satisfying to all!

Tempera Painting[1]

From the crude beginnings in Byzantine and early Christian art and, as some early writers suggest, but without definite proof, from the ancient Greeks, a traditional tempera process came into general use throughout Italy.

Egg Tempera process.

The pure egg-yolk technique was described by Cennino Cennini in a treatise on painting as practiced at least as early as the fourteenth century; it was well established in his day, and his knowledge and training using this technique came to him from the studio of his idol, Giotto.

Giotto 1267-1337.

Egg tempera continued to be the principal medium used for easle painting in Europe until the development of artistic oil painting. As the art expert Eastlake expresses it, the early Italian painters, though taking great care to produce durable works, made no attempt to lessen executive difficulties tending rather to overcome such difficulties by superior skill.

Madonna and Child by Duccio. Tempera with gold ground on wood, 1284, Siena.

The Flemish and other Northern painters departed from the early Italian methods, using new materials, aimed at ease of manipulation, and producing works technically excellent to a degree impossible to duplicate by strict adherence to the egg tempera technique of Cennini.These methods and materials are supposed to have been initiated about the year 1400 in Flanders and thereafter introduced into Venice.

Figure above shows a map of Europe in the fifteenth century. The area in Northern Europe that is dark red is Flanders, which was controlled by the Dukes of Burgundy (in France) during this time period. We now call the art and culture of this area, Flemish.

Though the medium of oil paint had been in use since the late middle ages, the artists of the North were the first to exploit what this medium had to offer. Using thin layers of paint, called glazes, they created a depth of color that was entirely new, and because oil paint can imitate textures far better than fresco or tempera, it was perfectly suited to creating that illusion of reality that was so important to Renaissance artists and patrons. In contrast to oil paint, tempera dries quickly and to create an illusion of three dimensional form, the paint has to be applied in short thin brushstrokes, like cross-hatching. In the Northern Renaissance, we see artists making the most of oil paint—creating the illusion of light reflecting on metal surfaces or jewels, and textures that appear to replicate real fur, hair, wool or wood.

The period from the beginning of the fifteenth century to about the middle of the sixteenth century produced tempera paintings of a high degree of technical excellence, which serve as models for the tempera techniques of today.

The Holy Family.

Tempera on panel, 39 x 32 cm, unframed.

Around the same time (beginning about 1400 AD) new materials began to be discovered or perfected. A commercial renaissance began, a result of which was the wide distribution and availability of raw materials. Traders brought supplies from the Orient, and the manufacture of finished goods on a larger scale improved quality and gave uniformity to materials in common use.

Linseed oil had been known and used for ordinary decorative and protective coatings from the earliest recorded periods of European history, but it was a crude, mucilaginous product unlike well-made material we know now as raw linseed oil; however, thinners such a turpentine were virtually unknown. Processes for the purification of linseed oil in the modern sense began to be published about the year, that is 1400.

Distillation was known to writers of the third century AD, but it was not practiced commercially until the fifteenth century, at which time its products, alcohol and other volatile solvents for varnishes and paints, began to be widely available.

The process of alkali refining linseed oil.

The aim and taste of the artists and their public should be taken into consideration when a study of these changes in techniques is made. Vasari and other writers who lived in a day when tempera was becoming obsolete, and when novel effects produced by oils were widely acclaimed were often prone to condemn the tempera technique from the viewpoint of the tastes, fashions, and styles of their day. Tempera painting was condemned by them as inferior to oil because of the very qualities which make it appeal to its present-day users.

Fred Wessel's tempera painting. He is a professor of printmaking at the Hartford Art School at University of Hartford in Connecticut. He teaches tempera painting, lithography and drawing. Fred did his BFA at Syracuse University in New York and MFA at the University of Massachusetts He is very much inclined towards Italian Renaissance and takes his inspiration from the same. He says: "The ever-changing inner light that radiates from gold leaf used judiciously on the surface of a painting, and the use of pockets of rich, intense colors that illuminate the picture's surface impressed me deeply".

During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, some tempera paintings were done on canvas, which had been introduced with the oil painting technique, by that time in full swing. Tempera as a universally used medium in a high state of technical development may be considered to have become obsolete by the end of the sixteenth century.

In following any recipes or instructions of former times, even up to nineteenth-century methods, it is important to remember that the quality, character, and nomenclature of many raw materials have undergone changes, and to be familiar with the artistic or pictorial aims of the period for which the methods were intended.

The statement, made in accordance with general opinion, that tempera painting became obsolete more than three hundred years prior to its present revival, is true only so far as its wide general usage is concerned. Examples and records of isolated works done with older materials can be cited for almost every age, but these individual experiments had small influence either on the general practice among painters of the time or on the major part of the painters' own works. The present revival of tempera owes its extent to the adaption of the technique to the requirements of modern taste, since it makes possible effects particularly well suited to certain modern artistic aims, which did not exist in the recent past. In the early part of the 20th Century its seems to have received its greatest impetus in Germany, although isolated groups of English and American painters have also pioneered its use.

Title and Artist: The Dancer Anita Berber by Otto Dix (German).

Techniques and Materials: oil and tempera on plywood.

Some partial use of tempera by American painters of the early nineteenth century is recorded. Scully recommended that colors be ground in skim milk (crude casein). A ground made from skim milk and white lead was one of his favorites, and he also mentioned the use of colors ground in skim milk for underpaintings, carrying this work as far towards completion as possible, then finishing with transparent oil and varnish glazes. An emulsion of flour paste and Venice turpentine is also mentioned.

Reference:

[1] The Artist's Handbook of Materials and Techniques, R. Mayer, (ed. E. Smith) 4th Edition, Faber and Faber, London (1981).

No comments:

Post a Comment