Preamble

For you convenience I have listed below posts on this blogspot that featured Museums and Galleries.

When Rainforests Ruled

Some Textiles@The Powerhouse Museum

Textile Museum in Tilburg (The Netherlands)

Eden Gardens

Maschen (Mesh) Museum@Tailfingen

Museum Lace Factory@Horst(The Netherlands)

Expressing Australia – Art in Parliament House

TextielLab & TextielMuseum – 2013

The Last Exhibition @ Galerie ’t Haentje te Paart

Paste Modernism 4 @ aMBUSH Gallery & The Living Mal

El Anatsui – Five Decades@Carriageworks

The Australian Museum of Clothing and Textiles

Louisiana Museum of Modern Art

Nordiska Museet (The Nordic Museum)

Tarndwarncoort (Tarndie)

Egyptian Museum Cairo - Part I

Egyptian Museum Cairo - Part II

Masterpieces of the Israel Museum

Introduction

The 26th of January is a holiday in Australia. It is called “Australia Day”, marking the date in 1788 when Captain Arthur Phillip took formal possession of the colony of New South Wales and for the first time raised the British flag in Sydney Cove. In the early 1880’s the day was known as “First Landing”, “Anniversary Day” or “Foundation Day”. In 1946 the Commonwealth and State governments agreed to unify the celebrations on 26th January and call it “Australia Day”. The day became a public holiday in 1818 (on its 30th anniversary).

“The founding of Australia” (in itself a provocative title since it ignores the presence of the first peoples).

(State Library of Victoria, H8731, color reproduction of painting in the Tate Gallery by Algernon Talmage).

Since 1994 all States and Territories (Northern Territory and Australian Capital Territory) celebrate Australia Day together on that actual day. On this day ceremonies welcome new citizens or honor people who have done a great service to the country. Generally, the public celebrate the day with BBQs hosting family and friends, and more formally, there are organized contests, parades, performances, fireworks etc.

Bankstown City Council Citizenship Ceremony.

Australia Day 2012.

National Australia Day Council, which was founded in 1979, views Australia Day as “… a day to reflect on what we have achieved and what we can be proud of in our great nation,” and a “day for us to re-commit to making Australia an even better place for the generations to come”.

To many of the first peoples of this land - the Australian Aboriginals - there is little to celebrate on that day since it reminds them of a deep loss; the loss of their sovereign rights to their land, loss of family, loss of the right to practice their culture.

Australians protesting against celebrating “Australia Day”.

“Australia Day is 26th January, a date whose only significance is to mark the coming to Australia of the white people in 1788. It’s not a date that is particularly pleasing for Aborigines,” says Aboriginal activist Michael Mansell. “The British were armed to the teeth and from the moment they stepped foot on our country, the slaughter and dispossession of Aborigines began.”

Michael Mansell.

Aboriginal people call it “Invasion Day”, “Day of Mourning”, “Survival Day” or, since 2006, “Aboriginal Sovereignty Day”. The latter name reflects that all Aboriginal nations are sovereign and should be united in the continuous fight for their rights.

Mansell believes that Australia celebrates “…the coming of one race at the expense of another. Australia is the only country that relies on the arrival of Europeans on its shores as being so significant it should herald the official national day,” he says. “The USA does not choose the arrival of Christopher Columbus as the date for its national day. Like many other countries its national day marks independence.”

To many of the first peoples and to the latter-day arrivals, a more fitting day on which to celebrate a united (not divided) Australia that has a unique shared experience, would be to celebrate the 1st February as Australia Day. On this day in 1901 six Australian States (New South Wales, Tasmania, South Australia, Western Australia, Queensland and Victoria) federated to form the Commonwealth of Australia, making it independent of the United Kingdom. Sadly, this most important “independence day” is barely acknowledged and celebrated around the country. This post serves to commemorate and celebrate this date rather than the 26th of January.

Federal Parliament House in Canberra.

Art in the Federal Parliament House (Canberra, Australia)

Construction of the permanent Australian Federal Parliament house began in 1980. Previously the Federal Parliament was housed in Victoria; that is, from 1901 to 1927 Parliament House in Melbourne was the seat of the Federal Parliament of Australia. Due to the intervention of events such as World War I the provisional Parliament House (now called “Old Parliament House”) was not completed until 1927. Old Parliament House opened in 1927 and served as the home of Federal Parliament until 1988.

On 26 June 1980 the international architectural competition for the “new” Parliament House was won by Mitchell/Giurgola & Thorp Architects, with the construction managed by the Parliament House Construction authority. Parliament House was opened on the 9thj May 1988 and occupied by parliament for the first sittings in August of that year.

Forecourt of Parliament House with Michael Tjakamarra Nelson's pavement mosaic in the foreground.

A central part of the architecture was the extensive programs of works of art and craft commissioned and purchased by the Parliament House Construction authority.

This post mostly concentrates on textile art and prints on paper which is only a small aspect of art and craft items housed in the (Federal) Parliament House (Canberra, Australia) and so is just a vignette of the plethora of artworks that is spread throughout the galleries, suites, rooms, corridors, offices and the houses of parliament. To get a far more comprehensive insight of what can be viewed, the book – Art in Parliament House - is great source.

Designer: Michael Tjakamarra Nelson.

Place: Forecourt of Parliament House.

Fabricators: W. McInntosh, A. Rossi and F. Colusso.

Technique: Moasic pavement of granite and mortar.

Comment: Designed for the forecourt mosaic, the work derives from the traditional sand paintings of the Warlpiri people in the central Australian desert. It depicts a gathering of men from many different groups of the kangaroo, wallaby, and goanna ancestors, congregating to talk and enact important ceremonial obligations. The painting has complex layers of mythological meanings known only to the Walpiri elders.

Artist: Arthur Boyd. Untitled (detailed view of one section of the tapestry).

Fabricator: Australian Tapestry Workshop.

Place: Great Hall.

Interpretation: Leonie Bessant.

Weavers: Leonie Bessant, Sue Carstairs, Irene Creedon, Robyn Daw, Owen Hammond, Kate Hutchinson, Pam Joyce, Peta Meredith, Robyn Mountcastle, Joy Smith, Jennifer Sharp, Irja West.

Technique: Tapestry. Wool, mercerized cotton and linen weft on seine warp.

Size: 9.18 x 19.90 meters.

Comment: This untitled work oil on canvas was the basis for the Great Hall Tapestry (Australian Tapestry Workshop). The evocation of “land” is central to the Australian psyche. The Australian forested landscape, is dense not because of the thickness of the trees and their foliage, but rather because of the thinness of trunk and foliage and their parallel straightness offers a far compactness of experience. Moreover, their appearance is not divorced from the leanness of the first peoples.

Designer: Kay Lawrance.

Details from the final stages of the Parliament House embroidery before assembly. The assembled work, 16 meters long, is displayed on the first floor gallery of the Great Hall.

Fabricators: Members of the Embroiderers’ Guild of Australia.

Place: Great Hall.

Technique: Embroidery. Wool, cotton, synthetic fiber on linen.

Comment: The work was proposed by the Embroiderers’ Guild of Australia as a Bicentennial gift to the nation of their time and craft skills.

Lawrance’s design is a historical tableau of the Australian continent, depicting, in an inter-related series of panels, scenes commemorating the long Aboriginal tradition as well as the settlement and exploration of the land by Europeans, culminating in the contemporary reality of rural and urban life.

The individual contributions of more than 500 embroiderers from all part of Australia were carefully coordinated and assembled in Canberra.

The embroidery, some 16 meters long, retains the free-flowing line and subtle gradations of tone from Lawrance’s design, with its strength of composition and delicate rendering in pencil and water color.

Artist: Sally Robinson. Title: Kakadu.

Place: Committee Room.

Technique: Screen print in five parts.

Size: Each part: 110 x 59.8 cm.

Comment: Parliament in committee performs painstaking tasks such as refining legislation and conducting enquiries. The theme for the artworks in these rooms and in the joining corridors reflects artworks that employ the tools of an industrial society. Hence, Sally Robinson’s work utilizes such tools but does so in depicting the flora and fauna of modern day Kakadu.

Artist: Toni Robertson. Title: Economic Landscape No. 3. The marginlisation of Aboriginal people.

Place: Committee Room.

Technique: Screen print. One of a tryptich.

Size: 104 x 73 cm.

Comment: In her silk screen series – Economic Landscape - Toni Roberston juxtaposes the actions of government with a reality of the consequences of parliamentary action (or lack thereof) experienced by peoples stripped of power.

A number of hand woven rugs adorn the floors of Parliament House. Each gives a distinctive Australian ground coverings.

Designer: Lesley Dumbrell. Title: Terrazo

Place: Prime Minister’s suite rug.

Technique: Wool weft.

Designers: Liz Nettleton & Alun Leach-Jones. Title: Music of Colors.

Place: Library rug.

Technique: Wool weft on cotton seine warp.

Designers: Lise Cruickshank & Liz Nettleton. Three hand-woven rugs.

Place: Curve Wall Circulation Area.<

Technique: Wool weft on cotton, seine warp.

Hence, my vote for Australia Day would be the 1st February. It would unite all Australians rather than to divide them!

Reference:

[1] Expressing Australia – Art in Parliament House.

Preamble

For you convenience I have listed below posts on this blogspot that featured Museums and Galleries.

When Rainforests Ruled

Some Textiles@The Powerhouse Museum

Textile Museum in Tilburg (The Netherlands)

Eden Gardens

Maschen (Mesh) Museum@Tailfingen

Museum Lace Factory@Horst(The Netherlands)

Expressing Australia – Art in Parliament House

TextielLab & TextielMuseum – 2013

The Last Exhibition @ Galerie ’t Haentje te Paart

Paste Modernism 4 @ aMBUSH Gallery & The Living Mal

El Anatsui – Five Decades@Carriageworks

The Australian Museum of Clothing and Textiles

Louisiana Museum of Modern Art

Nordiska Museet (The Nordic Museum)

Tarndwarncoort (Tarndie)

Egyptian Museum Cairo - Part I

Egyptian Museum Cairo - Part II

Masterpieces of the Israel Museum

Introduction

Museum Lace Factory at Horst (The Netherlands) was the last lace making factory in North-West Europe. It closed its operation in 2006. It now serves as a constant reminder of a regional textile industry which spanned nearly eighty years of operation.

Creation of Growth and Bloom (2006).

Museum de Kantfabriek (Museum Lace Factory@Horst).

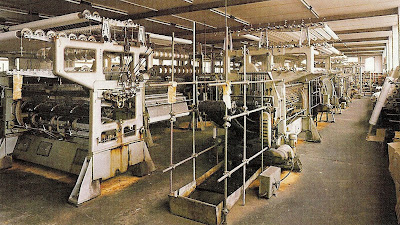

The Museum houses rattling machines in a factory setting, yielding a glimpse of the atmosphere of factory life from the 1930s onwards. The spinning machines provide a unique experience and insight into the making of lace as well as giving a glimpse of the textile industry that was once the base of the economy in the North Limburg region.

Exhibition: "Lace in North Limburg" (1995).

Resourceful farmers grew flax in order to produce linen, thereby creating a cottage weaving industry. Nowhere in the Netherlands was there such a significant concentration of home weavers. Hence a skill base of textile cottage workers was an important precedent in order to create a mechanised textile industry within the region.

Medieval dress with detachable sleeves, flax-linen gorget and wool hood - 13th Century.

The Museum mounts a number of local and international textile exhibitions as well as provides educational activities such as workshops, lectures and courses for the young and the elderly. All of the machines are operational and so they can still produce antique lace using thousands of gossamer threads. The Museum houses a shop in order to sell lace, books and other textile artefacts. It also houses a unique collection of old and contemporary textile art and crafts.

Helmie van der Riet's textile installation at Museum Lace Factory (2009).

Size: 5 x 5 x 4.5 m.

The Museum has the largest lending library in the Netherlands in the field of textile art and craft books. Its library houses more than 9000 books, which are available to borrow. It also features a special collection of ancient and modern objects that can be viewed via its permanent collection.

The Museum welcomes special purpose groups. It offers guided tours and has a public canteen for coffee or lunch. It provides special rooms so groups can engage in their own program of lectures or courses or workshops.

Lecture delivered to a sizeable group of visitors at the Museum.

Before we go into the history of the Museum - a must visit if your are in Limburg - I shall provide a brief history of the Netherlands.

A Brief History of The Netherlands[1]

In its early history, the Netherlands was mainly occupied by three Germanic tribes—the Frisians, the Saxons and the Franks. The borders of these tribes were not in line with today’s borders of the Netherlands. Frisians and Saxons were also found in England and Germany.

A 19th Century depiction of different Franks (AD 400-600).

Although the Dutch accepted one form of Dutch as their official language, that did not change the language as it was spoken among the locals. This is the reason why different names in The Netherlands can have the same literal meaning.

The English word "Dutch" derives from the German Deutsch ("German"). "Dutch" referred originally to both Germany and the Netherlands but came to be restricted to the people and language of The Netherlands when that country became independent in the seventeenth century. "Holland" and "The Netherlands" are often used as synonyms even though "Holland" refers only to the provinces of north and south Holland.

Girls in traditional Dutch outfits offering free cheese (Gouda) to sample in Gouda, The Netherlands.

Dutch national identity emerged during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, especially in the struggle for independence from Catholic Spain during the 'Eighty Year War' (1568–1648). The Dutch people received independence from the House of Habsburg in the Treaty of Munster in 1648. The Netherlands was temporarily unified with Belgium after the Congress of Vienna. The Catholic Belgium elite sought freedom from the Protestant Dutch, culminating in Belgium becoming independent in 1839.

The official language of the Netherlands is “standard” Dutch. This language is used in all official matters, by the media and at schools and universities. Dutch closely resembles German in both syntax and spelling. It freely borrows words and technical terms from French and especially from English.

The Netherlands is divided into twelve provinces. Amsterdam (730,000 inhabitants) is the capital, but the government meets in The Hague (440,000 inhabitants). Utrecht (235,000 inhabitants) is the transportation hub, while the port city of Rotterdam (590,000 inhabitants) constitutes the economic heartland. These four cities, together with a string of interconnected towns, form the Randstad, which has a population of 6,100,000.

Spring in Amsterdam.

The Dutch distinguish between two major cultural subdivisions in their nation. The most important distinction is between the Randstad (Rim City) and non-Randstad cultures. Randstad culture is distinctly urban, located in the provinces of North Holland, South Holland, and Utrecht. The non-Randstad culture corresponds to the historical divide between the predominantly Protestant North and the Catholic South, separated by the Rhine River.

Significant local variations of Dutch culture include: the Friesian culture in the extreme North and the Brabant and Limburg cultures in the South. The Southern culture was subject to discriminatory policies until the nineteenth century. The Friesians prize that their language and descent are from the ancient Friesian people, while the Limburgers and Brabantines emphasize their Southern culture and Catholic heritage.

Farmer couple in North Limburg costume of ca. 1900.

The complex relationship of the Dutch people with the sea is notable. The sea has historically been both an adversary as well as an ally. In the past, the Dutch repelled foreign invaders by deliberately piercing river dykes. However, if not for the extensive waterworks, 65 percent of the Netherlands would be flooded permanently. The Dutch take great pride in their struggle against the sea and the reclaiming of land, which they view as their mastery over nature.

Afsluitdijk, The Netherlands.

Dykes make such convenient highways.

The rapid expansion of the Dutch merchant fleet in the 17th Century enabled the establishment of a worldwide network of trade routes that created naval dominance and increasing wealth for the Dutch merchant class. Handicapped by a small population (ca. 670,000 inhabitants in 1622) and besieged by growing English and French might, the Dutch dominance of sea-trade routes began to decline.

Dutch Tall Ship.

Its sea trade and domination of Indonesia - which became a Dutch colony - informed the Dutch about such art techniques as Batik, which the Dutch imported back to the Netherlands.

Harmen C. Veldhuisen, Batik Belanda (1840-1940). Dutch Influence in Batik from Java History and Sources (1993).

The clearest example of national symbolism is the Dutch royal family. The queen is regarded as the embodiment of the Dutch Nation, and a symbol of hope and unity in times of war, adversity, and natural disaster. Her popularity is manifested annually at the celebration of Queensday on 30th of April. In particular, the capital, Amsterdam, is transformed into a gigantic flea market and open-air festival.

Queensday parties in Amsterdam.

Horst is a village in the province of Limburg. It is located in the municipality of Horst aan de Maas. Although the municipality is named after the village, Horst itself is not named as “Horst aan Maas,” since it does not lie on the river “Maas”. In 2007 Horst had a population of some 12,000 people.

Oudheidkamer of Horst.

Timelines: Creation of the Museum Lace Factory@Horst

18th December 1974.

Objects found from the excavations of Castle Ter Horst (1890) were placed in the providence of the Regional Museum Foundation,which had an Old Room dedicated to these objects that could be viewed by the community at large. A number of volunteers enabled this initiative to occur and moreover, assisted to administer it.

ca. 1990.

With the success of the Regional Museum Foundation’s Old Room it became obvious there was a need to " ... grow a local museum in Horst which the community should be proud of.” The Old Room was adapted to house temporary exhibitions as well as to expand the library in order to contain a larger collection of its local history.

January 2002.

A report was published suggesting that: "... Old Room at Horst should be exhibiting contemporary art as well as to develop a historical setting for visitors and to provide tourist information of the cultural heritage of the municipality of Horst aan de Maas.”

January 2003.

The municipality wanted to examine the possibility that the existing South Dutch Kantfabriek (Lace Factory) in Horst be given additional income by providing factory visits, thereby giving the factory an additional museum function.

March 2005

The City of Horst aan de Maas decided to preserve the South Dutch Kantfabriek (Lace Factory) and establish the Museum Kantfabriek (Museum Lace Factory) in its historic building.

23rd February 2006

The Foundation - Museum Lace Factory - was founded with the aim to collect, preserve and exhibit objects of interest for the history of the municipality of Horst aan de Maas and its surroundings in general, and moreover, in particular to display the Southern Dutch textile history. The new museum will showcase exhibitions, give lectures and courses as well as workshops. The artefacts and collections of the 'Old Room' to be included in the new museum’s collections.

Mid- 2006

Fund raising began and the inventory of the museum quickly increased in scope and size. The South Dutch Kantfabriek (Lace Factory) was purchased by the National Society of Maintenance, Development and Exploitation of Industrial Heritage.

2007

The permit for the museum was signed and extensive remodelling of the factory occurred in order to make it more suitable for its museum functions. South Dutch Kantfabriek (Lace Factory) was opened to the public in its new role as the Museum Lace Factory.

History of the South Dutch Kantfabriek (Lace Factory)

Andreas Hubert (Hub) Coumans was born in Nederweert on 6th November 1874. He was the son of Peter Joseph Coumans and Mary Agnes PoeII. On the 8th June 1909 he married Hendrika Hubertina Vossen. She was the daughter of John and Elisabeth Vossen and was born on the 3rd January 1882.

Miki, Hub Coumans Sr., Bep, Fien, Hub Jr., Maria Coumans.

The couple settled in Blerick, where they had three daughters (Fien, Bep and Miki) and a son who died a few weeks after birth. Hub was an accountant in a cigar factory. At the end of November 1920 the family moved to Tiling. On the 22nd of December 1921 Hendrika gave birth to their son - Hub Jr. In Tiling Hub Coumans was registered as a tobacco manufacturer being co-owner of a cigar factory in Tegelen.

In 1927 Hub Coumans was bought out of the business. His Bank advised him to invest his money in another company. Precisely at that time a company in Blerickse - "Maatschappij NV” – became bankrupt. Coumans came up with the idea to create a lace factory. He bought the lace machines from the bankrupt factory and searched for a building that was suitable to house lace making machines. He found a suitable building in Horst that was empty, but which had previously been a silk factory. Coumans rented this factory and together with his partner Gerard van der Star from Blerick, began in mid-1928 to manufacture lace. On the 12th of June, 1928 Coumans moved his family to Horst.

Coumans’ children enjoyed a good education. The three girls: Fien, Bep and Miki studied at a boarding school in Stein. Fien was an "urban" lady and felt that Horst was too provincial. She worked at various jobs, but mostly as a governess to "middle class" families. Before the war she worked in Liège, Amsterdam and Haarlem. During the war years she stayed in Horst and in 1946 she became a director of the lace factory. In 1947 her mother took over the management function from Fien and so once again Fien left Horst to became governess in Rosmalen and Haarlem.

Fien.

Bep studied to become a teacher. That was her profession until she married. In 1949 Bep with her husband Mathieu Kuijpers went to live in Venlo. In 1951 they moved back to Horst when Mathieu Kuijpers took on a co-directorship of the lace factory.

Bep.

Miki graduated in accounting and so she managed the accounts of the factory. From 1939 she was co-director of the lace factory. In 1946 she married Harry Peters and in 1951 she moved to the Randstad.

Miki.

Hub Jr. went to the textile school in Eindhoven. After the unexpected death of his father in 1943, Hub Jr. was appointed co-director lace factory. On 12th of October 1944 he died in an allied bombing raid on Horst.

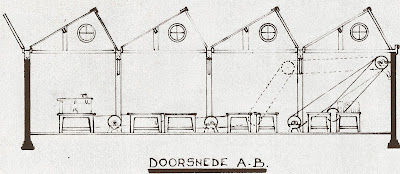

On the 31st of March, 1928 South Dutch Kantfabriek (Lace Factory) Horst was officially founded by Andreas Hubertus Coumans, and Gerard van der Star. On the 2nd April, they sought for planning permission to establish a lace factory at Horst at Americaamseweg. The factory would be 16 m long, 15 m wide and 4 m high. The building was equipped with electric lights and the machines would be set in motion by an electric motor of 20 hp. The factory would specialize in the production of lace and rubber bands. It was envisaged there would be six employees. The architect for construction of the building would be HPJ Duijf of Horst. On the 27th of April, 1928 planning was approved, provided that the factory would be operational prior to the 1st of January, 1929.

Hub Jr.

Two weeks later it was reported that the lace factory was still not fully operational, but the factory housed some fifty lace machines. The majority of machines were in operation and manufactured various types of lace producing up to of 70 meters of lace per hour. The machines were driven by electromotive force and they contained a large number of bobbins, which artfully swung together. If any thread broke the machines would be made to stop until the broken thread was repaired by a lace worker.

Lace Factory, Horst (1928).

The lace factory made sizeable profits in the 1920s to 1930s judging by Hub Coumans other business ventures. Moreover, the Kantfabriek Horst had already become known outside the municipal boundaries, and even in Dutch East Indies. For example, there was a sizeable article in the weekly magazine "Panorama/Our South" on the 27th January, 1938 about the company.

In 1938 Coumans had decided to focus his business interest entirely on the manufacturing of lace. To this end Coumans bought the entire inventory of lace factory Tebake Borne comprising of numerous machines and tools. These items were temporarily stored in the former cigar factory, which was next to the lace factory. In December 1938 he applied to the municipality permission to the convert the neighboring cigar factory into a lace factory. The 24 and 36 lace machines would be placed on the ground floor and first floor of this building, respectively.

Diameter of the Lace factory.

On the 11th of September, 1939 Coumans bought all the shares (20 shares) of his partner Gerard van der Sterren. Miki was then appointed a co-director at the tender age of 23 years old. In May 1940 the new factory was ready. The machines from the former old, rented premises were transferred to the new building. A piece of wall had to be removed in order to install the machines from the old building. The new plant was operational in June 1940. However, World War II intervened.

Cigar Factory Arsifa converted to manufacturing lace (1930).

From 10th May 1940 Horst was occupied by the Germans. The lace production fell to very low levels, because demand for lace drastically fell in the Dutch East Indies (which was occupied by the Japanese). The production of lace was discontinued and production of rayon products was initiated using a vastly reduced workforce.

On the 7th of November, 1942, Andreas Hubertus Coumans, founder of the South Dutch Kantfabriek (Lace Factory) died at the age of 68 years old. His daughter Miki was the only director of the Kantfabriek. On May 31, 1943, the 21 year-old Hub Coumans Jr., brother of Miki, became a co-director of the South Dutch Kantfabriek (Lace Factory).

On the 12th October, 1944 the allies dropped some forty bombs on Horst. Many people were killed in the raid. Hub Coumans Jr. and his fiancée Rikie Peeters were among the victims. Thirty-three victims of the bombing (including Hub Coumans Jr.) were buried on the 14th October,1944.

The butchery and restaurant - Gerade Peeters - was demolished by the bomb explosion. Far right of the picture is Coumans demolished home.

Hub Coumans Jr.

On the 22nd November, 1944 the first British tank entered Horst. The English army took up shelter in the attic of the lace factory. After the liberation of Horst production of lace slowly reappeared using the cotton that was held in stock. The Coumans family had meanwhile moved to the house next to the factory. The Dutch textile industry came back to life due to the increase demand for clothing. New markets were found.

The Lace Factory (1946).

On the 24th of April, 1946 Miki married Harry Peters and she resigned as director of the lace factory. Her sister Fien took over the directorship. She was only eighteen years old. In December, 1947, she was succeeded by her mother - Ms. Coumans. The reasons why Fien relinquished her directorship is not known.

Mother and daughters (Bep, Miki and Fien) (1945).

Since the death of her husband in 1942 Mrs Coumans was the only owner of the lace factory. From December 1947 she also took over the management of the company. The upstairs was used as a warehouse.

In 1948 the lace factory had a total of 68 employees, which signifies that the factory was extremely profitable. Mrs Coumans nor her daughters were technically minded and so had little knowledge about technical aspects of the machines. They turned to their foreman, Kenn Jeu Kleeven, to oversight all technical aspects of the business, including the training of employees on the machines.

Mrs Coumans lived alone in the house next door to the lace factory. She was still the sole shareholder of the factory, but in October 1950 she decided to donate four shares to each of her three daughters. She had a total of 28 shares in December 1953, and in December 1954 gave her daughters a further two shares. Hence each daughter was therefore in possession of six shares and as Mrs Coumans had 22 shares, she was still the largest shareholder in the company.

On the 2nd May, 1951, Mathieu Kuijpers - husband of Bep Coumans - was appointed co-director of the lace factory. Mrs Coumans was now 69 years old and she thought it was time for her to ease up on running the company. In her old age she was found daily at the factory, even just to have a chat with the staff. Mathieu Kuijpers was a salesman. He was responsible for the purchase, sales and orders for shipment. Mathieu Kuijpers also had no knowledge of the technical aspects of the factory.

A much older Mathieu Kuipers.

On the 19th of June, 1952 the company was granted a building application to alter the layout of the factory. The factory was divided into six areas, each with a different operation: winding, yarn warehouse, room layout, jacquard machinery and two hallways.

In the 1950s, fashion changed very quickly. Synthetic fibers (nylon, rayon etc.) were increasingly preferred over natural products such as cotton and linen. New machines were needed (e.g. raschel) in which nylon lace could be knitted. A number of factories were closed because of the emerging nylon/rayon industry. Forced redundancies occurred at the lace factory because of these changing trends.

The raschel machines were made by Mayer in Germany, which is near Frankfurt am Main. A representative of the lace factory visited Mayer in order to assess whether the South Dutch Kantfabriek should invest in these new machines. The directors of the company decided to continue operations since it was the only lace factory in the Netherlands that could produce both nylon raschel lace and cotton bobbin lace. The company had old machines that were made in the twenties and thirties. Therefore, the company decided to sell some of these old machines, refurbished others, sent some of the more dilapidated machines to a scrap merchant and purchase some new raschel machines.

In 1958 Sef Kellenaers, who worked in the lace factory for ten years, was asked by the director Kuijpers to go to the Mayer Factories in Germany in order to become acquainted with the new raschel machines. Sef was a father for the first time and so was reluctant to go. However, he capitulated and went to Germany by train and stayed in a guesthouse in Obertshausen. He would travel once a fortnight to visit his family in Horst over two days. For the rest of the time he was in the Mayer factory learning about the operational and technical aspects of raschel machines from top to bottom. A thorough knowledge was necessary because for each new pattern that would be knitted on these machines, the machine would have to be completely rebuilt. Raschel lace was a surface of hexagonal mesh (tulle), in which the pattern of the lace was knitted simultaneously. The lace was knitted with a width of approximately 1.80 meter.

In 1958 the first raschel machine arrived in Horst. Sef accompanied the journey of the machine personally. A number of machines were purchased in the following years, yielding a total of eight raschel machines, including two very large machines (twice as wide). A further two machines were purchase from a bankrupt factory.

The first raschel machine with Sef Kellenaers in Horst (1958).

Sef Kellenaers was sent back for two weeks to Mayer factories to learn how to convert the pattern chains in order to create new patterns. The entire conversion of a raschel machine (chain pattern and the correct number of needles in the right place settings) still took 2 to 3 weeks. As the lace factory got more raschel machines, it was worthwhile to purchase additional links and metal rods in order that new patterns could be quickly manufactured. Hence the machines would not have to stand idle for large slabs of time. Sef was for years the only person in the lace factory who knew the raschel machine inside out. He could not afford to be sick even for a single day. Director Kuijpers appreciated this and so every morning when he toured the factory, he would leave Sef a packet of cigarettes.

Pattern Necklace from a Raschel machine.

Note: Chain belts and needles of the raschel machines needed to be reset for each different pattern.

Raschel machines could knit lace cloth for bridal gowns, blouses and for the lingerie industry. The machines could produce a lace role in the day, which consisted of 100 meters of lace. Lace cloth could be knitted (or bridal gowns) ladies blouses and lingerie industry with 50 to 136 edges at once. Nylon lace edges were a versatile product finding their way into the lingerie industry, festive and carnival clothing, and in the lining of coffins. On the other hand, cotton bobbin lace was mainly manufactured for the more prestigious clothing industry, but was also used as closet lining.

Portion of a sample book of raschel lace.

On the 12th May, 1965 Mrs Coumans died at the age of 83-years-old. From that moment Mathieu Kuijpers was the sole director.

Mrs Coumans in old age.

In the late sixties, the orders for nylon lace declined and there was also less demand for cotton bobbin lace. The Southern Dutch Kantfabriek started to manufacture "hair curl stockings". These were plastic thread on the bobbin machines, which yielded braided sleeves that were used in the manufacture of hair curlers. Each size hair curlers had its own color: red, blue, yellow, etc. The machines could produce approximately 30 meters per hour. The hair curl stockings were sold per kg at home and abroad (e.g., Belgium). In the late sixties a large part of the clothing industry disappeared in the Netherlands because of competition from low-wage countries.

The lace industry was profitable and so the Southern Dutch Kantfabriek flourished. A building permit was tendered on the 11th March, 1970 that applied for the establishment of a warehouse, on the flat roof of the rear building of the former house of Mrs. Coumans, and above it the establishment of a canteen/kitchen and corridor. Meanwhile, all factories in the Netherlands that only made cotton bobbin lace became unprofitable and were closed. There were several new lace factories that were established that only made nylon lace. Southern Dutch Kantfabriek invested well and sold their four or five year old machines.

Nylon raschel lace machines (2001).

After 1970 the demand for environmentally friendly and natural products increased again. The demand for nyIon lace decreased and the demand for cotton bobbin lace resurged. In the late seventies the demand for cotton bobbin lace was so great that a large investment was made in new kIosmachines. Factories that only made nylon lace went through a deep depression and some did not survive. South Dutch Kantfabriek continued to be profitable.

The family did not want the company to fall into foreign hands. However, Fien was unmarried, her sister Bep was married to Mathieu Kuijpers (sole director) but they were childless, but Miki had two children. She lived with her husband Harry Peters, and her daughter Erica and son Aart in Den Bosch. Mathieu Kuijpers went to Den Bosch to ask if Aart might be interested to come and work in the family business, with the aim of him eventually taking over the management of the company. However, Aart had very different plans. Aart, during his studies, worked in MTS electronics in an auto shop and he was often present in car race environments. Meanwhile he was trying to get his hospitality diplomas, because he and his two friends wished to take over a catering company. After much deliberation, Aart decided to go to Horst and join the company. He was looking for a room in Venlo and on the 1st of January, 1978 began his career in the lace factory. He was 22 years old. Aart had to learn the entire production process. His technical insight came in handy. Gradually he learned the whole process from the rinsing of yarn to the finishing of lace. He was trained with the help of the company staff. He had a rounded knowledge of the production of lace and trims. He also learned how to operate the machines and to repair them. Aart concluded that there had been little investment in modernizing machinery. Most machines were old and some were in very bad condition.

50th Anniversary in Mrs van Helden's home: Fien, Fried van Helden, Aart Peters, Mrs. Helden and children (1985).

On the 17th November 1980, the shareholders decided that Fien Coumans should return to help with the management of the company. On the 11th November 1983 Aart Peters was appointed as a co-director. In 1983 the management of the company relied on these three people. Director Kuijpers slowly retreated from the management of the company and on the 18th July, 1984 he suspended himself as director. He died on 9th April, 1986 at the age of 76.

Fien who was 76 years old lived next to the lace factory. Aart was married in 1981 to Gerry Geerts. They lived in Horst not far from the lace factory. Gerry, if the housework allowed, was increasingly helpful in the operations of the lace factory.

Lace Factory (2001).

In the eighties, the lace factory had good times and bad times. The interest in lace remained strong as lace remained a sensitive fashion article. However, major customers purchased lace from cheaper countries in Eastern Europe. Furthermore, illegal sewing workshops in Amsterdam also competed with sales. In 1984 the Dutch government swept away most of the illegal sweatshops. The market for lace collapsed. The Southern Dutch Kantfabriek went through a deep recession. Most of the staff were retired or fired. The factory was left with only a handful of employees.

On the 9th June, 1990 director Fien Coumans died and from that time on Aart Peters was only the director of the South Dutch Kantfabriek. Together with his wife Gerry, he continued to be responsible for the overall management of the company. The company that his grandfather founded in 1928 remained financially viable through hard work, and employing as few staff as possible.

Gerry and Aart Peters (2009).

In the eearly nineties came another heyday for lace manufacture. Pop star Madonna wore lots of lace and the fashion industry hooked onto her clarion call. Additional staff had to be employed in order to keep up with the demand. However, the heyday for lace demand did not last long. The fashion industry is fickle at the best of times and so within a short period lace was no longer in demand. The demand for lace ebbed and flowed for years, but the valleys became much deeper and the peaks less high.

Madonna wearing lace gloves.

Stg. Oudheidkamer Horst and Kant Kring 't Klaske came to the South Dutch Kantfabriek stand. Because of regional interest in 1995 they organized - "Lace in North -Limburg" and in 2000 - "The Other Lace of 2000". Both times visitors come to the Old Room to see an exhibition of hand bobbin lace pieces. The lace club gave demonstrations in the Old Room of lacemaking and the couple Aart and Gerry Peters gave tours around the lace factory. Thousands of visitors used the opportunity to take a look at the last lace factory in the Netherlands. Many were not even aware of the existence of this factory. It was felt that this plant, its craftsmanship was truly unique and should certainly be preserved for the future. The government also shared that opinion. In 2000, the Kantfabriek was one of the Horster buildings that were nominated to be added to the monument list. During "Heritage" on Sunday, 10th September, 2000 the South Dutch Kantfabriek was one of the five Horster historic buildings that were opened to the public.

In 2002 the Department for Conservation stated:

"The former cigar factory has become a rare example of austere industrial construction in tight brick architecture. The exterior is largely intact and original. The most important values, however, lies in the fact that this multi-stage complex houses a production that cannot be traced elsewhere in the Netherlands. The various machines are important as part of the inventory, and as an essential link in the production. They are also rare. The complex is of local urban importance as an example of the then - historic characteristic spatial location of emerging activity along a road out of Horst.”

Around the 75th anniversary of the plant (in 2003) the manufacturing of lace was once again profitable. Lace was back in fashion. The old machines were still in business. They were rock solid devices that rarely broke down. Nevertheless, they made a lot of noise. Hence the machines were only run during business hours. Sometimes the lace factory got such large orders that it would have to work in two shifts but because of the limits placed on running the machines it was not possible to do so. The couple Peters never considered switching to more modern, computer-controlled machines. That move would have meant a huge investment and the factory was not that profitable.

Gerry Peters was asked regularly whether visitors could tour the factory. This was not always possible for O H & S requirements. Sometimes tours were arranged on a Friday afternoon when production ceased. Guided tours nevertheless became a welcome financial addition, since the demand for lace was still not strong.

The Old Room of Horst had a large collection of the textile history of Horst and was faced with space problems. The group saw some possibilities to organize a portion of the lace factory as a museum, thereby bringing their collection into the building. The municipality of Horst aan de Maas supported this plan. It was reasoned that it would be great for the tourist trade if visitors could view old techniques of lace making. The couple Peters was also excited by this idea. However, a lot of planning needed to be put in place before such an idea could become reality.

Early in 2003 the municipality commissioned Monument House Limburg to conduct a study into the feasibility of a museum in the historical lace factory. The feasibility study showed that after only a few years the museum would even make a profit. Enthusiastically they started fundraising, but financing the renovation of the building would be costly and so the plans for it to become a museum went on the back burner.

Early in 2005 Mr. Peters - owner of the lace factory - stopped the manufacture of lace. The number of the factory’s customers of lace was drastically reduced because of competition from abroad. Despite the fact that the building was listed as a national monument it was not eligible for a municipal subsidy in order to renovate the building. Hence Mr. Peters was considering selling the machines to manufacturers and selling the building to a developer. Discussions were initiated again with Textile Associations who argued for the preservation of this unique industrial heritage. At the end of 2005 the Society for the Preservation of Industrial Heritage wanted the lace factory restored. On the 15th of September 2006 the Society purchased the South Dutch Kantfabriek. Six cotton lace machines, a raschel machine for nylon lace and some auxiliary machinery were taken over by a new foundation - "Museum Lace Factory" Horst. The other spindle machines (about 30 pieces) and auxiliary machinery were sold and transported to India. The older raschel machines were sold to a trader for scrap. Kantfabriek had now become a part of the rich textile history of the Netherlands.

Exhibition at Museum Lace Factory - Grow and Bloom (2006) - Lace Outfit.

References:

[1] Geschiedenis van de N.V. Zuid Nederlandsche Kantfabriek.

[2] https://www.everyculture.com/Ma-Ni/The-Netherlands.html