Preamble

For your convenience, I have listed below posts that also focus on rugs.

Navajo Rugs

Persian Rugs

Caucasian Rugs

Turkish Rugs

Navajo Rugs of the Ganado, Crystal and Two Grey Hills Region

Navajo Rugs of Chinle, Wide Ruins and Teec Nos Pos Regions

Navajo Rugs of the Western Reservation

Introduction

The Navajo Indians called themselves – Taa dine - which is translated as The People. When the Spanish began penetrating the South West of America, Indian villages fell under Spanish rule, except for the Navajo. They survived the Spanish invasion by fading back into their Canyon lands.

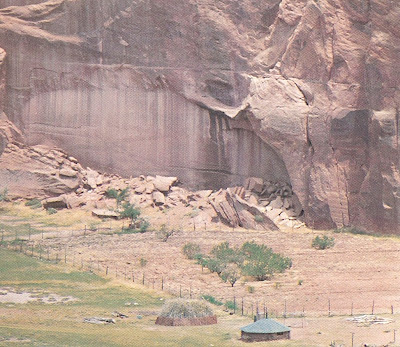

The homeland and spiritual sanctuary for the Navajo people is the Canyon de Chelly and its tributaries – Canyon del Muerto and Monument Canyon – where some still live and work in their traditional ways.

Courtesy reference[1].

Spain, Mexico nor the United States - during the first seventeen years of sovereignty in the South West – were unable to defeat or dominate the Navajo people. The Spaniards called them begrudgingly - “The Lords of the Earth”. It was only Colonel Kit Carson “scorched earth” strategy of burning their crops and homes, killing their sheep and horses that eventually forced them to submit to foreign rule.

Dating to the 1870s, the trading post of D. Lorenzo Hubbell at Ganado continues to serve the needs of the Navajo peoples.

Courtesy reference[1].

As with all indigenous peoples around the world the invasion of Europeans with their technical superiority quickly decimated indigenous governance structures and in most cases left them in a state of free-fall with respect to their existence. However, today the Navajo number ca. 200,000, with 50,000 under sixteen years of age. Twenty-five thousand go to school. However, only half of the Navajos speak and can write in English, but over 97% are fluent in their native language. The Navajo nation now governs itself by an elected tribal chairman and by regional representatives to council. Discovery of petroleum in the 1920s led to the formation of the first Navajo central government.

Schools are accessible to most Navajo families, but sometimes it is necessary that a family living many difficult miles away send the children to boarding school.

Navajo’s art meanders its course through many different art media but perhaps one of its most important distinct artistic voice rests with the unique designs of its rugs. Such tribal arts centers as the Tribal Arts and Craft Center at Willow Rock or the Museum of Northern Arizona both provide significant art outlets for the Navajo weavers.

Some Navajo weaves are displayed for sale at the Museum of Northern Arizona's annual Navajo Craftsman show.

Courtesy reference[1].

This post could not have been written nor the procured images displayed without accessing the tome – “Navajo Rugs” by Don Dedera[1] – a must read!

Navajo Women Weavers

By physique and language Navajo were related to Asia, by kinship with Athapaskan tribes of Western Canada and interior Alaska. Anthropologists believe that as nomadic hunters and gatherers they drifted in small bands from 1100 to 1500 AD to settle in America’s South West – now known as the Four Corners – where New Mexico, Colorado, Utah and Arizona join.

To survive in the land of little water, they became farmers, borrowing the techniques of their Pueblo neighbors. They took up sand painting and adopted the Puebloan religion and social structure. When the Spanish came, they obtained the domestic livestock from Spanish flocks. Farming became secondary to their primary role of following their flock of sheep across the vast tablelands - seeking water and food for their flocks. The Navajo initially saw sheep as a food stock rather than a source for textiles.

The "Lords of Earth" droving their sheep across their tablelands.

Courtesy reference[1].

Weaving artistic designs and textiles flowered among the Pueblo III peoples (1050 – 1300 AD). Their descendants continued to weave on unique vertical looms during the centuries that the Navajos were infiltrating Puebloan territory from the North. The Pueblo men grew cotton, and so learnt how to spin and wove cotton into textiles.

Typical Navajo/Puebloan vertical loom.

Courtesy reference[1].

Sheep were a catalyst for Navajo women to learn weaving techniques from the Pueblo men. The Navajo women tended the sheep as it was below the dignity of the Navajo men to care for such a tame flock in between seeking for water and food for their flock. The Navajo women learnt the Puebloan weaving techniques and applied it to woolen fiber (not cotton) in order to produce woolen textiles.

Pueblo style, all wool hand spun blanket was collected in 1871-72 during the exploration of the Colorado river by J.W. Powell.

Description: Natural white, indigo blue and natural black.

Courtesy San Diego Museum of Man.

The Navajo women had a passion for color. Today weavers restrict themselves to natural white, brown and black, or mixtures of these. Some use aniline dyes, but most draw upon a hundred or more natural dye recipes which utilize roots, barks, flowers, leaves and fruits of dried plants from their regions. Dyes were set with various chemicals, and sometimes they used their urine to do so.

Among the earliest dated Navajo weaves is this dress fragment recovered from Canyon del Muerto’s Massacre Cave, where Spaniards had slain a number of Indians in 1804-1805.

Courtesy reference[1].

Among the eight distinct Navajo weaves is the plain or basket weave, commonplace and possibly the oldest weave. Warp and weft are equally distinct in the finished fabric.

Plain or basket weave.

Courtesy reference[1].

Also quite common is the diamond twill, borrowed from Pueblo weavers. A relief pattern is created by arranging the heddles to elevate groups of warp.

Diamond weave.

Courtesy reference[1].

Another familiar pattern is the tapestry weave. The warp is covered by beating down the weft to compress the threads together. It is a plain but very effective weave.

Tapestry weave.

Courtesy reference[1].

Aside from the regular tapestry weaving on a standard loom arrangement, some Navajo women specialize in other long-standing techniques. Several variations of twill weaving went into saddle blankets and larger rugs. An array of as many of five heddles lets the weaver choose unequal sets of warps, such as under-three, over-one, to produce textured diamonds, terraces and zig-zags. In such rugs designs of the two faces of the fabric are the same, but the colors are opposed.

Weaver at Hubbell Trading Post works on a re-creation of an original 19th Century rug.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Navajo Artistry

Below is just a vignette of Navajo artistry that is available in reference[1].

Classic serae, ca. 1870. Tightly woven to the texture of the canvas, containing natural white handspun, indigo handspun, yellow, green and red Saxony and 5.5 inch bands of red bayeta near each end.

Size: 48.5 x 68 inches.

Courtesy reference[1].

The essence of Germantown in this serape entirely of commercial wool; yarn in ten colors on a cotton warp, ca. 1899-1900.

Size: 52/54 x 74 inches.

Courtesy reference[1].

The rich Germantown commercial wool colors are enhanced by outlining of the Teec Nos Pos style, bears serrated, overall diamond patterns and fringes sewn on after weaving.

Size: 34.5 x 155 inches.

Courtesy reference[1].

This table runner is a fringed textile of Germantown yarn in design dominated by a multi-hued, eight pointed star; ca. 1890.

Size: 25 x 39 inches.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Elongated central diamond of a typical red Ganado is captured in a modern weaving by Elizabeth and Helen Kirk; handspun native wool, and pre-dyed commercial “wool-top” – also handspun.

Size: 36 x 60 inches.

Courtesy reference[1].

An intermediate type of two Grey Hills, ca. 1945; in dyed black, natural white, and two shades of brown and gray by carding natural wools together.

Size: 46 x 63.5 inches.

Courtesy reference[1].

A two Grey Hills tapestry created in 1974 by Dorothy Mike, with threads spun as many as ten times to equal fineness of linen.

Size: 27 x 37 inches.

Courtesy reference[1].

Teec Nos Pos tapestry of commercial yarns by Ruth Yabany.

Size: 85 x 144 inches.

Courtesy reference[1].

Ella Yazzie Bia of white clay, Arizonia, was commissioned to copy a design in Read Mullan’s catalog. In six months the job was completed but with tiny variations in design.

Size: 39 x 63 inches.

Courtesy of reference[1].

The bird pictorial is by Rena Mountain.

Courtesy reference[1].

Reference:

[1] D. Dedera, Navajo Rugs, 3rd Edition, Northland Publishing, Flagstaff (1994).

For your convenience, I have listed below posts that also focus on rugs.

Navajo Rugs

Persian Rugs

Caucasian Rugs

Turkish Rugs

Navajo Rugs of the Ganado, Crystal and Two Grey Hills Region

Navajo Rugs of Chinle, Wide Ruins and Teec Nos Pos Regions

Navajo Rugs of the Western Reservation

Introduction

The Navajo Indians called themselves – Taa dine - which is translated as The People. When the Spanish began penetrating the South West of America, Indian villages fell under Spanish rule, except for the Navajo. They survived the Spanish invasion by fading back into their Canyon lands.

The homeland and spiritual sanctuary for the Navajo people is the Canyon de Chelly and its tributaries – Canyon del Muerto and Monument Canyon – where some still live and work in their traditional ways.

Courtesy reference[1].

Spain, Mexico nor the United States - during the first seventeen years of sovereignty in the South West – were unable to defeat or dominate the Navajo people. The Spaniards called them begrudgingly - “The Lords of the Earth”. It was only Colonel Kit Carson “scorched earth” strategy of burning their crops and homes, killing their sheep and horses that eventually forced them to submit to foreign rule.

Dating to the 1870s, the trading post of D. Lorenzo Hubbell at Ganado continues to serve the needs of the Navajo peoples.

Courtesy reference[1].

As with all indigenous peoples around the world the invasion of Europeans with their technical superiority quickly decimated indigenous governance structures and in most cases left them in a state of free-fall with respect to their existence. However, today the Navajo number ca. 200,000, with 50,000 under sixteen years of age. Twenty-five thousand go to school. However, only half of the Navajos speak and can write in English, but over 97% are fluent in their native language. The Navajo nation now governs itself by an elected tribal chairman and by regional representatives to council. Discovery of petroleum in the 1920s led to the formation of the first Navajo central government.

Schools are accessible to most Navajo families, but sometimes it is necessary that a family living many difficult miles away send the children to boarding school.

Navajo’s art meanders its course through many different art media but perhaps one of its most important distinct artistic voice rests with the unique designs of its rugs. Such tribal arts centers as the Tribal Arts and Craft Center at Willow Rock or the Museum of Northern Arizona both provide significant art outlets for the Navajo weavers.

Some Navajo weaves are displayed for sale at the Museum of Northern Arizona's annual Navajo Craftsman show.

Courtesy reference[1].

This post could not have been written nor the procured images displayed without accessing the tome – “Navajo Rugs” by Don Dedera[1] – a must read!

Navajo Women Weavers

By physique and language Navajo were related to Asia, by kinship with Athapaskan tribes of Western Canada and interior Alaska. Anthropologists believe that as nomadic hunters and gatherers they drifted in small bands from 1100 to 1500 AD to settle in America’s South West – now known as the Four Corners – where New Mexico, Colorado, Utah and Arizona join.

To survive in the land of little water, they became farmers, borrowing the techniques of their Pueblo neighbors. They took up sand painting and adopted the Puebloan religion and social structure. When the Spanish came, they obtained the domestic livestock from Spanish flocks. Farming became secondary to their primary role of following their flock of sheep across the vast tablelands - seeking water and food for their flocks. The Navajo initially saw sheep as a food stock rather than a source for textiles.

The "Lords of Earth" droving their sheep across their tablelands.

Courtesy reference[1].

Weaving artistic designs and textiles flowered among the Pueblo III peoples (1050 – 1300 AD). Their descendants continued to weave on unique vertical looms during the centuries that the Navajos were infiltrating Puebloan territory from the North. The Pueblo men grew cotton, and so learnt how to spin and wove cotton into textiles.

Typical Navajo/Puebloan vertical loom.

Courtesy reference[1].

Sheep were a catalyst for Navajo women to learn weaving techniques from the Pueblo men. The Navajo women tended the sheep as it was below the dignity of the Navajo men to care for such a tame flock in between seeking for water and food for their flock. The Navajo women learnt the Puebloan weaving techniques and applied it to woolen fiber (not cotton) in order to produce woolen textiles.

Pueblo style, all wool hand spun blanket was collected in 1871-72 during the exploration of the Colorado river by J.W. Powell.

Description: Natural white, indigo blue and natural black.

Courtesy San Diego Museum of Man.

The Navajo women had a passion for color. Today weavers restrict themselves to natural white, brown and black, or mixtures of these. Some use aniline dyes, but most draw upon a hundred or more natural dye recipes which utilize roots, barks, flowers, leaves and fruits of dried plants from their regions. Dyes were set with various chemicals, and sometimes they used their urine to do so.

Among the earliest dated Navajo weaves is this dress fragment recovered from Canyon del Muerto’s Massacre Cave, where Spaniards had slain a number of Indians in 1804-1805.

Courtesy reference[1].

Among the eight distinct Navajo weaves is the plain or basket weave, commonplace and possibly the oldest weave. Warp and weft are equally distinct in the finished fabric.

Plain or basket weave.

Courtesy reference[1].

Also quite common is the diamond twill, borrowed from Pueblo weavers. A relief pattern is created by arranging the heddles to elevate groups of warp.

Diamond weave.

Courtesy reference[1].

Another familiar pattern is the tapestry weave. The warp is covered by beating down the weft to compress the threads together. It is a plain but very effective weave.

Tapestry weave.

Courtesy reference[1].

Aside from the regular tapestry weaving on a standard loom arrangement, some Navajo women specialize in other long-standing techniques. Several variations of twill weaving went into saddle blankets and larger rugs. An array of as many of five heddles lets the weaver choose unequal sets of warps, such as under-three, over-one, to produce textured diamonds, terraces and zig-zags. In such rugs designs of the two faces of the fabric are the same, but the colors are opposed.

Weaver at Hubbell Trading Post works on a re-creation of an original 19th Century rug.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Navajo Artistry

Below is just a vignette of Navajo artistry that is available in reference[1].

Classic serae, ca. 1870. Tightly woven to the texture of the canvas, containing natural white handspun, indigo handspun, yellow, green and red Saxony and 5.5 inch bands of red bayeta near each end.

Size: 48.5 x 68 inches.

Courtesy reference[1].

The essence of Germantown in this serape entirely of commercial wool; yarn in ten colors on a cotton warp, ca. 1899-1900.

Size: 52/54 x 74 inches.

Courtesy reference[1].

The rich Germantown commercial wool colors are enhanced by outlining of the Teec Nos Pos style, bears serrated, overall diamond patterns and fringes sewn on after weaving.

Size: 34.5 x 155 inches.

Courtesy reference[1].

This table runner is a fringed textile of Germantown yarn in design dominated by a multi-hued, eight pointed star; ca. 1890.

Size: 25 x 39 inches.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Elongated central diamond of a typical red Ganado is captured in a modern weaving by Elizabeth and Helen Kirk; handspun native wool, and pre-dyed commercial “wool-top” – also handspun.

Size: 36 x 60 inches.

Courtesy reference[1].

An intermediate type of two Grey Hills, ca. 1945; in dyed black, natural white, and two shades of brown and gray by carding natural wools together.

Size: 46 x 63.5 inches.

Courtesy reference[1].

A two Grey Hills tapestry created in 1974 by Dorothy Mike, with threads spun as many as ten times to equal fineness of linen.

Size: 27 x 37 inches.

Courtesy reference[1].

Teec Nos Pos tapestry of commercial yarns by Ruth Yabany.

Size: 85 x 144 inches.

Courtesy reference[1].

Ella Yazzie Bia of white clay, Arizonia, was commissioned to copy a design in Read Mullan’s catalog. In six months the job was completed but with tiny variations in design.

Size: 39 x 63 inches.

Courtesy of reference[1].

The bird pictorial is by Rena Mountain.

Courtesy reference[1].

Reference:

[1] D. Dedera, Navajo Rugs, 3rd Edition, Northland Publishing, Flagstaff (1994).

2 comments:

Well, once again thank you, Marie! Currently have students writing short essays with thesis concerning cultural appropriation in textiles and design!! Great background knowledge as one focus is the head dress used in the Victoria Secrets Fashion Parade, given Navajo perspectives of women and modesty. Would you ever post any of your academic teachings on this topic? We are also looking at Rodarte's use of ABTSI mark making in latest collection. :) much appreciation. X

Hello Flora,

Thank you for your kind comments !

You may like to see my blog post on Aboriginal Art Appropriated by Non-Aboriginal Artists art essay. It doesn't specifically talk about textiles and design but does talk about cultural appropriation and issues about that topic. It may be of interest to some of your students - please click on the following link to read the essay http://artquill.blogspot.com.au/2012/08/aboriginal-art-appropriated-by-non.html

Marie-Therese x

Post a Comment