Preamble

For your convenience I have listed below other post in this series:

Silk Designs of the 18th Century

Woven Textile Designs In Britain (1750 to 1763)

Woven Textile Designs in Britain (1764 to 1789)

Woven Textile Designs in Britain (1790 to 1825)

19th Century Silk Shawls from Spitalfields

Silk Designs of Joseph Dandridge

Silk Designs of James Leman

Silk Designs of Christopher Baudouin

Introduction

The period between 1764 to 1789 spanned the peak year (1764) for the export of English silks to the American colonies – the quantity of which was never surpassed. Eventually printed cotton became victorious and so the export decline of English silks became so drastic that it led to the demise of the silk industry in Britain.

The excellent essays of Natalie Rothstein’s about eighteenth century silks has resulted in two further major publications, namely, Barbara Johnson’s Album of Fashion and Fabrics (1987), and Silk Designs of the Eighteenth Century in the Collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum (1990).

The images and information contained in this post have been procured from a great book – The Victoria & Albert Museum Textile Collection, N, Rothstein, Canopy Books, Paris (1994). Her research on the collection is comprehensive and insightful. A “must have” for your ArtCloth library collection.

Today’s post will concentrate on the period from 1764 to 1789 in this on-going series.

Woven Textile Designs in Britain (1764 to 1789) [1]

The crisis of 1764-66 was compounded by several elements, namely:

(i) The public fashion tastes hit the silk industries all over Europe, eventually ensuring that printed cottons were considered by the public at large to be of high fashion, even though such opinions were not necessarily held by the elite.

(ii) The economic state of the London silk industry was such that it simply over produced and so the expensive price of silk products could not be sustained, since new markets could not be found for the product (lack of diversification) and old markets were shrinking.

Riots in Spitalfield.

A supply of good, cheap, raw silk could not be found, so that silks remained intrinsically expensive. The English industry blamed the import of French silks for the over supply. The unemployment amongst the English weavers was so bad, that a subscription list was published in order to assist them in these lean years. In the two years of unrest, demonstrations against their plight was peaceful, although Robert Carr, a well-known mercer had his windows smashed on suspicion that he was selling French silks and abuse was hurled at the John Russel (the Duke of Bedford) for remarks he had made about the weavers in the House of Lords.

John Russell - the fourth Duke of Bedford (painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds).

The London Gazette first came into print in 1665 and was originally called the Oxford Gazette - as it was decided that the King and his court should move to Oxford, along with the Gazette, in order to escape the plague. Once the plague dissipated, The Gazette returned to London. The copy (dated 1765) described the riots at Spitalfields as follows:

'Riots among the Spitalfields weavers, for many a century, were of frequent occurrence. The greatest riot was in 1765, when the weavers marched on parliament to protest against the defeat of a bill to tax imported silks.

They terrified the House of Lords into an adjournment, insulted several hostile members, and in the evening attacked Bedford House, and tried to pull down the walls, declaring that the duke had been bribed to make the treaty of Fontainebleau, which had brought French silks and poverty into the land.

The Riot Act was then read, and detachments of the Guards called out. The mob then fled, many being much hurt.'

The scale and organization of these popular protests frightened authorities. In 1763 the Journeymen issued their first list of "Prices" – wages to be accepted by both sides of the industry and in 1766 a law was passed making the formation of a trade union illegal. A period of bitter industrial dispute ensued.

The Spitalfields Act of 1773 onwards gave a half a century of industrial peace. A 'List of Prices' was agreed and 'new works' added as they became fashionable. The Spitalfields magistrates were given power to enforce them. The system worked until its repeal in 1826.

Silk Designs – 1764 to 1789

The quality of English silks remained excellent over the next few years (see image below).

Weaver’s sample, Spitalfields, ca. 1764.

Taffeta, brocaded in silver strip and thread, with a self-colored pattern in the ground.

Comment[1]: The sample is English and has an English inscription on the back, but has been inserted in a French order book.

Size: 14.25” x 21” (36.2 x 53.3 cm).

Courtesy of reference[1].

Manufacturers fell back on the formula they acquired from France; that is, a meander and garland facing one way, with a bunch of mixed roses and carnations facing the other. Increasingly a stripe was introduced as an additional motif, while the scale and size of patterns diminished. The less pattern there was, the cheaper it was to produce but this was offset by the decreased motivation that good artists had to design for the silk industry. There were plenty of pretty silk patterns as demonstrated by the four silk patterns displayed below.

Woven Silk, Spitalfields, ca. 1765-70.

Comment[1]: Tobine (cannel) ground, with green pattern wefts, brocaded with white silk and white silk fries.

Repeat Size: 3.5 x 1.75” (31.8 x 24.8 cm).

Courtesy of reference[1].

Nevertheless, if the market demanded large, original designs, then these would have been made. Below is a simple version of the meander and opposing sprig, and it is thus difficult to date.

Woven silk, Spitalfields ca. 1760-64.

Comment[1]: Tabby ground, with a white flushing warp.

Repeat Size: 7.5 x 4.67 “ (19 x 12.4 cm).

Courtesy of reference[1].

By 1770, the English silk industry had to adjust to a radical change in demand. There was now no market for furnishing silks - wallpapers, printed cottons and fine worsteds became much more important – and moreover, the market for dress silks was also changing. The modern softer, drape styles no longer required the heavy silks of the previous seventy years with their large-scale designs shown off on a sack-backed dress. The full length of a dress was no longer available to the designer since fashion now decreed deep flounces sometimes in contrasting materials. During the 1770s Neo-Classical taste began to affect both the patterns themselves and garments for which they were intended. The following two patterns from 1775 are typical.

Sample from silk weaver’s pattern book of Batchelor, Ham & Perigal, Splitalfield, ca. 1772 – 73.

Comment[1]: Satin and tobine (cannel) stripes with additional flush pattern.

Size: 6.75 (17.1 cm) high, together.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Woven silk, Spitalfields, ca. 1772-73.

Comment[1]: Tobine (cannel) ground, brocaded with colored silks and silk fries.

Repeat Size: 4.5 x 9.5” (11.4 x 24.1 cm).

Between 1770 and 1775 repeats were halved in length from 8 to 9 inches to as little as 3 or 4 inches in order to make woven silk more affordable. The two silk patterns below are typical of this design change.

Samples from silk weaver’s book of Batchelor, Ham & Perigal, Spitalfields, 1776, 1777.

Comment[1]: Brocaded taffeta.

size: 6” (15.2 cm) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Designers turned for inspiration to embroidery, printed cottons and the patterns of French silks (which were very similar in both style and coloring). The two silk patterns below from the pattern books of Batchelor, Ham and Perigal, supplement the evidence of surviving silks. Both demonstrate a leopard spot motif, which recurs until the early 19th Century, but is better carried out as a printed motif.

Woven silk, Spitalfields, ca. 1768-70.

Comment[1]: Tobine (cannel) ground with satin stripes, brocaded in colored silks, with additional flush pattern.

Repeat Size: 17 x 20” (38.1 x 48.9 cm).

Courtesy of reference[1].

Samples from silk weaver’s book of Batchelor, Ham & Perigal, Spitalfields, ca. 1772.

Size: 4.75” (12 cm) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

The wriggle and spot of the silk pattern below, dated 1777, is another seen more effectively in the background of a printed cotton fabric. It was originally a pattern effect used in quilting. By contrast, even the ribbon, stripe and garland, which belong to the silk designers, were now used effectively by the calico-printers. The quality, which is particular to woven silk – its texture – was of no importance in a marketing sense for nearly all the samples and many of the surviving dresses were made from taffeta – for Spring – and satin – for the Winter season. The contrast in weave and types of thread, so important in previous centuries, was now abandoned.

Samples from silk weaver’s book of Batchelor, Ham & Perigal, Spitalfields, ca. 1777.

Comment[1]: Satin with a flush pattern.

Size: 4” (10.2 cm) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Within their limited field, the silks of the 1770s were nevertheless charming. Soft pinks contrasted with deeper chenille, delicate shades of green abound, with miniature Neo-Classical devices made by flush patterns.

Samples from silk weaver’s book of Batchelor, Ham & Perigal, Spitalfields, ca. 1776, 1777.

Comment[1]: Lightweight taffeta with a flush pattern made on a “monture” (i.e. draw loom).

Size: 2.5” (6.3 cm) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Samples from silk weaver’s book of Batchelor, Ham & Perigal, Spitalfields, ca. 1776, 1777.

Comment[1]: Brocaded Taffeta.

Size: 6” (15.2 cm) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

The two above silk patterns are delightful but hardly exciting, except in a historical sense. The above silks were worn at the moment America was declaring its War of Independence, although from 1776 to 1783 hardly any silks were exported to America, which had been London’s major overseas customer. It was the merchant class on the eastern seaboard and their families who had bought fashionable silks. Many suffered politically in later years since they were loyalists. Even though the American market quickly recovered after the war, silks were no longer at the forefront of fashion and so the American market quickly downsized. Even though men’s silk waistcoats were becoming less expensive due to the fact that they shrank in scale and weight of decoration, fashionable men were now sporting embroidered waistcoats.

In the 1780s a marked decline in the use of flower designs in silk patterns became the order of the day. Stripes, zig-zags (on a minute scale compared with the 1750s), doodles, stars, and spots became the favorite motifs.

Samples from silk weaver’s book of Batchelor, Ham & Perigal, Spitalfields, ca. 1779.

Comment[1]: Satin. Zig-zags.

Size: 4.5” (11.4 cm) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Samples from silk weaver’s book of Batchelor, Ham & Perigal, Spitalfields, ca. 1781, 1782.

Comment[1]: Figured satin. Doodles.

Size: 2” (5 cm) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

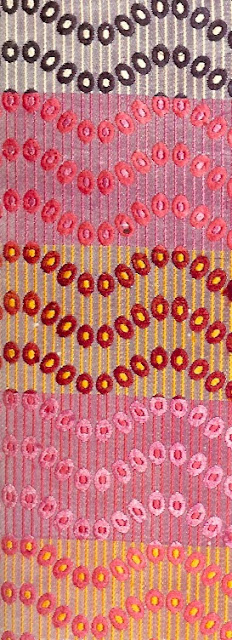

Samples from silk weaver’s book of Harvey, Ham & Perigal, Spitalfields, ca. 1786.

Comment[1]: Spots.

Size: 9.25” (23.5 cm) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

In addition there were some extraordinary optical effects worthy of the 20th Century, while belt buckles sold well in the 1770s. Dark grounds for the "Winter Season" became increasingly fashionable from the late 1770s, as they were in chintz. The Maze & Steer pattern book of 1786 to about 1791 highlights silk patterns of that era.

Samples from silk weaver’s book of Harvey, Ham & Perigal, Spitalfields, ca. 1786.

Comment[1]: Satin with figured stripes.

Size: 5” (12.7 cm) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Samples from silk weaver’s book intended for waistcoats. Maze & Steer, ca. 1786, 1787.

Comment[1]: Figured satins.

Size: 3” (7.6 cm) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

The above silk patterns were fundamentally embroidered designs adapted for another medium – for it was in these years that the Lyon Chambre de Commerce was bitterly complaining about the unfair competition from embroiderers. The vast majority of waistcoats surviving from the 1780s and 1790s were embroidered and whilst the silk waist coat patterns shown above are fair, they cannot compare with the splendid French embroidered rivals.

When Eden’s Free Trade Treaty was being negotiated with France in 1786, the silk industry in London was sufficiently strong and vigorous to secure exemption from its provisions, so that French silks remained excluded from England and vice versa.

The first attempts to set up a gauze industry in Paisley were apparently made by Spitalfields masters in the late 1780s and 1790s.

Reference:

[1] The Victoria & Albert Museum Textile Collection, N, Rothstein, Canopy Books, Paris (1994).

For your convenience I have listed below other post in this series:

Silk Designs of the 18th Century

Woven Textile Designs In Britain (1750 to 1763)

Woven Textile Designs in Britain (1764 to 1789)

Woven Textile Designs in Britain (1790 to 1825)

19th Century Silk Shawls from Spitalfields

Silk Designs of Joseph Dandridge

Silk Designs of James Leman

Silk Designs of Christopher Baudouin

Introduction

The period between 1764 to 1789 spanned the peak year (1764) for the export of English silks to the American colonies – the quantity of which was never surpassed. Eventually printed cotton became victorious and so the export decline of English silks became so drastic that it led to the demise of the silk industry in Britain.

The excellent essays of Natalie Rothstein’s about eighteenth century silks has resulted in two further major publications, namely, Barbara Johnson’s Album of Fashion and Fabrics (1987), and Silk Designs of the Eighteenth Century in the Collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum (1990).

The images and information contained in this post have been procured from a great book – The Victoria & Albert Museum Textile Collection, N, Rothstein, Canopy Books, Paris (1994). Her research on the collection is comprehensive and insightful. A “must have” for your ArtCloth library collection.

Today’s post will concentrate on the period from 1764 to 1789 in this on-going series.

Woven Textile Designs in Britain (1764 to 1789) [1]

The crisis of 1764-66 was compounded by several elements, namely:

(i) The public fashion tastes hit the silk industries all over Europe, eventually ensuring that printed cottons were considered by the public at large to be of high fashion, even though such opinions were not necessarily held by the elite.

(ii) The economic state of the London silk industry was such that it simply over produced and so the expensive price of silk products could not be sustained, since new markets could not be found for the product (lack of diversification) and old markets were shrinking.

Riots in Spitalfield.

A supply of good, cheap, raw silk could not be found, so that silks remained intrinsically expensive. The English industry blamed the import of French silks for the over supply. The unemployment amongst the English weavers was so bad, that a subscription list was published in order to assist them in these lean years. In the two years of unrest, demonstrations against their plight was peaceful, although Robert Carr, a well-known mercer had his windows smashed on suspicion that he was selling French silks and abuse was hurled at the John Russel (the Duke of Bedford) for remarks he had made about the weavers in the House of Lords.

John Russell - the fourth Duke of Bedford (painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds).

The London Gazette first came into print in 1665 and was originally called the Oxford Gazette - as it was decided that the King and his court should move to Oxford, along with the Gazette, in order to escape the plague. Once the plague dissipated, The Gazette returned to London. The copy (dated 1765) described the riots at Spitalfields as follows:

'Riots among the Spitalfields weavers, for many a century, were of frequent occurrence. The greatest riot was in 1765, when the weavers marched on parliament to protest against the defeat of a bill to tax imported silks.

They terrified the House of Lords into an adjournment, insulted several hostile members, and in the evening attacked Bedford House, and tried to pull down the walls, declaring that the duke had been bribed to make the treaty of Fontainebleau, which had brought French silks and poverty into the land.

The Riot Act was then read, and detachments of the Guards called out. The mob then fled, many being much hurt.'

The scale and organization of these popular protests frightened authorities. In 1763 the Journeymen issued their first list of "Prices" – wages to be accepted by both sides of the industry and in 1766 a law was passed making the formation of a trade union illegal. A period of bitter industrial dispute ensued.

The Spitalfields Act of 1773 onwards gave a half a century of industrial peace. A 'List of Prices' was agreed and 'new works' added as they became fashionable. The Spitalfields magistrates were given power to enforce them. The system worked until its repeal in 1826.

Silk Designs – 1764 to 1789

The quality of English silks remained excellent over the next few years (see image below).

Weaver’s sample, Spitalfields, ca. 1764.

Taffeta, brocaded in silver strip and thread, with a self-colored pattern in the ground.

Comment[1]: The sample is English and has an English inscription on the back, but has been inserted in a French order book.

Size: 14.25” x 21” (36.2 x 53.3 cm).

Courtesy of reference[1].

Manufacturers fell back on the formula they acquired from France; that is, a meander and garland facing one way, with a bunch of mixed roses and carnations facing the other. Increasingly a stripe was introduced as an additional motif, while the scale and size of patterns diminished. The less pattern there was, the cheaper it was to produce but this was offset by the decreased motivation that good artists had to design for the silk industry. There were plenty of pretty silk patterns as demonstrated by the four silk patterns displayed below.

Woven Silk, Spitalfields, ca. 1765-70.

Comment[1]: Tobine (cannel) ground, with green pattern wefts, brocaded with white silk and white silk fries.

Repeat Size: 3.5 x 1.75” (31.8 x 24.8 cm).

Courtesy of reference[1].

Nevertheless, if the market demanded large, original designs, then these would have been made. Below is a simple version of the meander and opposing sprig, and it is thus difficult to date.

Woven silk, Spitalfields ca. 1760-64.

Comment[1]: Tabby ground, with a white flushing warp.

Repeat Size: 7.5 x 4.67 “ (19 x 12.4 cm).

Courtesy of reference[1].

By 1770, the English silk industry had to adjust to a radical change in demand. There was now no market for furnishing silks - wallpapers, printed cottons and fine worsteds became much more important – and moreover, the market for dress silks was also changing. The modern softer, drape styles no longer required the heavy silks of the previous seventy years with their large-scale designs shown off on a sack-backed dress. The full length of a dress was no longer available to the designer since fashion now decreed deep flounces sometimes in contrasting materials. During the 1770s Neo-Classical taste began to affect both the patterns themselves and garments for which they were intended. The following two patterns from 1775 are typical.

Sample from silk weaver’s pattern book of Batchelor, Ham & Perigal, Splitalfield, ca. 1772 – 73.

Comment[1]: Satin and tobine (cannel) stripes with additional flush pattern.

Size: 6.75 (17.1 cm) high, together.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Woven silk, Spitalfields, ca. 1772-73.

Comment[1]: Tobine (cannel) ground, brocaded with colored silks and silk fries.

Repeat Size: 4.5 x 9.5” (11.4 x 24.1 cm).

Between 1770 and 1775 repeats were halved in length from 8 to 9 inches to as little as 3 or 4 inches in order to make woven silk more affordable. The two silk patterns below are typical of this design change.

Samples from silk weaver’s book of Batchelor, Ham & Perigal, Spitalfields, 1776, 1777.

Comment[1]: Brocaded taffeta.

size: 6” (15.2 cm) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Designers turned for inspiration to embroidery, printed cottons and the patterns of French silks (which were very similar in both style and coloring). The two silk patterns below from the pattern books of Batchelor, Ham and Perigal, supplement the evidence of surviving silks. Both demonstrate a leopard spot motif, which recurs until the early 19th Century, but is better carried out as a printed motif.

Woven silk, Spitalfields, ca. 1768-70.

Comment[1]: Tobine (cannel) ground with satin stripes, brocaded in colored silks, with additional flush pattern.

Repeat Size: 17 x 20” (38.1 x 48.9 cm).

Courtesy of reference[1].

Samples from silk weaver’s book of Batchelor, Ham & Perigal, Spitalfields, ca. 1772.

Size: 4.75” (12 cm) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

The wriggle and spot of the silk pattern below, dated 1777, is another seen more effectively in the background of a printed cotton fabric. It was originally a pattern effect used in quilting. By contrast, even the ribbon, stripe and garland, which belong to the silk designers, were now used effectively by the calico-printers. The quality, which is particular to woven silk – its texture – was of no importance in a marketing sense for nearly all the samples and many of the surviving dresses were made from taffeta – for Spring – and satin – for the Winter season. The contrast in weave and types of thread, so important in previous centuries, was now abandoned.

Samples from silk weaver’s book of Batchelor, Ham & Perigal, Spitalfields, ca. 1777.

Comment[1]: Satin with a flush pattern.

Size: 4” (10.2 cm) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Within their limited field, the silks of the 1770s were nevertheless charming. Soft pinks contrasted with deeper chenille, delicate shades of green abound, with miniature Neo-Classical devices made by flush patterns.

Samples from silk weaver’s book of Batchelor, Ham & Perigal, Spitalfields, ca. 1776, 1777.

Comment[1]: Lightweight taffeta with a flush pattern made on a “monture” (i.e. draw loom).

Size: 2.5” (6.3 cm) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Samples from silk weaver’s book of Batchelor, Ham & Perigal, Spitalfields, ca. 1776, 1777.

Comment[1]: Brocaded Taffeta.

Size: 6” (15.2 cm) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

The two above silk patterns are delightful but hardly exciting, except in a historical sense. The above silks were worn at the moment America was declaring its War of Independence, although from 1776 to 1783 hardly any silks were exported to America, which had been London’s major overseas customer. It was the merchant class on the eastern seaboard and their families who had bought fashionable silks. Many suffered politically in later years since they were loyalists. Even though the American market quickly recovered after the war, silks were no longer at the forefront of fashion and so the American market quickly downsized. Even though men’s silk waistcoats were becoming less expensive due to the fact that they shrank in scale and weight of decoration, fashionable men were now sporting embroidered waistcoats.

In the 1780s a marked decline in the use of flower designs in silk patterns became the order of the day. Stripes, zig-zags (on a minute scale compared with the 1750s), doodles, stars, and spots became the favorite motifs.

Samples from silk weaver’s book of Batchelor, Ham & Perigal, Spitalfields, ca. 1779.

Comment[1]: Satin. Zig-zags.

Size: 4.5” (11.4 cm) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Samples from silk weaver’s book of Batchelor, Ham & Perigal, Spitalfields, ca. 1781, 1782.

Comment[1]: Figured satin. Doodles.

Size: 2” (5 cm) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Samples from silk weaver’s book of Harvey, Ham & Perigal, Spitalfields, ca. 1786.

Comment[1]: Spots.

Size: 9.25” (23.5 cm) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

In addition there were some extraordinary optical effects worthy of the 20th Century, while belt buckles sold well in the 1770s. Dark grounds for the "Winter Season" became increasingly fashionable from the late 1770s, as they were in chintz. The Maze & Steer pattern book of 1786 to about 1791 highlights silk patterns of that era.

Samples from silk weaver’s book of Harvey, Ham & Perigal, Spitalfields, ca. 1786.

Comment[1]: Satin with figured stripes.

Size: 5” (12.7 cm) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Samples from silk weaver’s book intended for waistcoats. Maze & Steer, ca. 1786, 1787.

Comment[1]: Figured satins.

Size: 3” (7.6 cm) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

The above silk patterns were fundamentally embroidered designs adapted for another medium – for it was in these years that the Lyon Chambre de Commerce was bitterly complaining about the unfair competition from embroiderers. The vast majority of waistcoats surviving from the 1780s and 1790s were embroidered and whilst the silk waist coat patterns shown above are fair, they cannot compare with the splendid French embroidered rivals.

When Eden’s Free Trade Treaty was being negotiated with France in 1786, the silk industry in London was sufficiently strong and vigorous to secure exemption from its provisions, so that French silks remained excluded from England and vice versa.

The first attempts to set up a gauze industry in Paisley were apparently made by Spitalfields masters in the late 1780s and 1790s.

Reference:

[1] The Victoria & Albert Museum Textile Collection, N, Rothstein, Canopy Books, Paris (1994).

No comments:

Post a Comment