Preamble

For your convenience I have listed below other post in this series:

Silk Designs of the 18th Century

Woven Textile Designs In Britain (1750 to 1763)

Woven Textile Designs in Britain (1764 to 1789)

Woven Textile Designs in Britain (1790 to 1825)

19th Century Silk Shawls from Spitalfields

Silk Designs of Joseph Dandridge

Silk Designs of James Leman

Silk Designs of Christopher Baudouin

Introduction

There are a number of publications featuring the textile design collection held in the Victoria and Albert museum. Recently, Natalie Rothstein’s research into eighteenth century woven textile designs has resulted in a major publication. The images and information contained in this post have been procured from her great book – The Victoria & Albert Museums Textile Collection, N. Rothstein, Canopy Books, Paris (1994). Her research into the collection is comprehensive and insightful. The images and her analysis have been reproduced below.

Woven Textiles in Britain (1790 to 1825)[1]

The two decades from 1790 to 1810 were the worst that the European silk industry had experienced. Clearly the French revolution, which resulted in the loss of the French Court and so the loss in demand for finery in clothing, was certainly a factor, albeit not “the” factor. In fact, it was the devastating change in fashion modes that was the real determinant, which resulted in a dramatic slump in demand for silk clothing.

The slump hit London in 1792 when once more public subscriptions lists were opened for starving journeymen. The “throwsers” felt it in the following year when orders failed to come from London. Such a downturn was not evidenced from pattern books, since the master weavers had to prepare patterns for every season irrespective of the economic conditions. To complicate matters, England suffered a general economic recession, after which there was a slow recovery that lasted until the end of the century. Note: Silk throwing is the industrial process where silk that has been reeled into skeins, is cleaned, receives a twist and is wound onto bobbins. The people who do this are called “throwsers”.

From 1790 to 1797 pattern materials were still woven, although they were inferior in scope or originality compared to those from 1700 to 1770. From that period until 1805 there were hardly any patterns on fashionable silks, or on muslins, which had replaced them.

The dark grounds - popular in the 1780s - continued in popularity early in the 1790s, with colors such as Etruscan red and black being the order of the day, often graced with pseudo-Classical patterns. Fashionable ladies and men wore these as dresses and waistcoats, respectively. The lack of interest in woven patterns generally resulted in designs that were no longer needing to be developed season by season. In this period the beginnings of historicism is evident, which plagued British textile designs ever since.

Compare the two patterns below. Apart from skirt flounces, there was little opportunity for the designer. Also the styles in France and England continued to be the same. For example, Barbara Johnson has a dress like the pattern below, which she noted was French.

Sample from a silk weaver’s pattern book, Harvey, Ham & Perigal, Spitalfields, 1786.

Figured Satin.

Size: 23.5 cm (9.25 inches) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Sample from a silk weaver’s pattern book, Jourdain and John Ham, Spitalfields, 1802.

All woven with metal thread.

Size: 8.9 cm (3.5 inches).

Courtesy of reference[1].

The Neo-Classical motifs continued to be architectural. For example, the rosettes below would not have been out of place if they were mouldings around a door-frame.

Sample from a silk weaver’s pattern book, Harvey, Ham & Perigal, Spitalfields, Winter 1790.

Striped and figured satins.

Size: 13.3 cm (5.25 inches) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Public imagination was fired by campaigns in Egypt and so patterns contained pyramids and palms (see pattern below), but nothing as adventurous as the pseudo-Egyptian hieroglyphics, which were converted by Duddings in the early 19th Century into designs suitable for cotton furniture.

Sample from a silk weaver’s pattern book, probably from the firm of Jourdain and John, Ham, Spitalfields, ca. 1790-94.

Striped and figured satin.

Size: 30.5 cm (12 inches) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

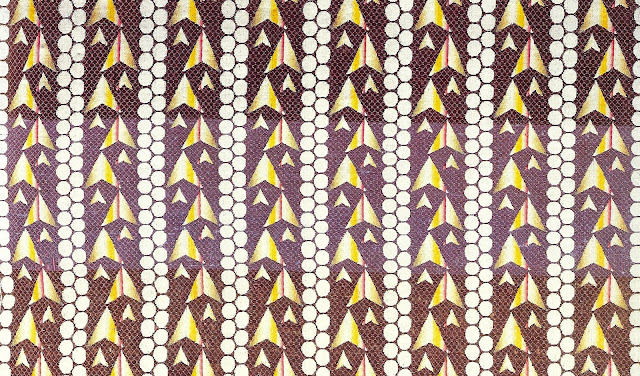

Chiné materials in bold colors, such as the yellow and black of the pattern below, were clearly very fashionable.

Sample from a silk weaver’s pattern book, probably from the firm of Jourdain and John, Ham, Spitalfields, ca. 1790-94.

Striped and figured satin.

Size: 20.3 cm (8 inches) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

The conjunction of several colorways, as in the pattern below, makes the effect even more startling.

Sample from a silk weaver’s pattern book, Harvey, Ham & Perigal, Spitalfields, Winter 1790. Striped and figured satin.

Size: 17.8 cm (7 inches) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

By the end of the century all that remain were little patterns (see below) and these hardly changed for the next twenty years.

Sample from a silk weaver’s pattern book, probably from the firm of Jourdain and John, Ham, Spitalfields, ca. 1798-99.

Size: 29.2 cm (11.5 inches) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Certain motifs appeared consistently. For example, the leopard spot was very popular.

Sample from a silk weaver’s pattern book intended for waistcoats, Maze & Steer, Spitalfields, 1786.

Figured satins.

Size: 8.2 cm (3.25 inches) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Another perennial is the fan of plates.

Sample from a silk weaver’s pattern book, probably from the firm of Jourdain and John, Ham, Spitalfields, ca. 1792-94.

Striped and figured satins.

Size: 25.4 cm (10 inches) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

From the period between 1795-1800 there was no major change in style. Even when a pattern such as that given below was repeated, it was not transformed or combined with some other motif, but simply turned on its side. The one style new to silk – Strawberry Hill Gothick – started as an almost invisible device in a self-colored pattern of about 1798. This was not the way new trends had started in the past. From Heideloff’s Gallery of Fashion, which started in 1794, it was only too evident that the fashionable world was wearing linen or cotton and using silk chiefly in ribbons for millinery. Dresses used decreasing amounts of silk materials – 10 yards of silk compared with 14 of a sack-back, while light weight satins and sarcenets used intrinsically less silk, since they were more loosely woven. Only ribbons and shawls remained and many of the latter were plain, edged with embroidery or imported from Kashmir.

From 1800 until about 1810 silks were lightweight, pale and most plain. Only the ribbons woven in Coventry have lively patterns. When there were any patterns on dress silks they tended to be small, self-colored, isolated sprigs very similar to those of the 1790s. Although the jacquard mechanism was invented in 1801, the first attempts to use it in England were not made until 1820-25, for these small patterns on silk seldom needed a draw loom, let alone its more expensive successor. The years from 1810 to 1825 were prosperous for Spitalfields. The industry was largely unaffected by distress and discontent which followed the end of the Napoleonic wars, for the journey men were protected by the Spitalfields Acts and the industry was not yet facing fierce competition from other centers in England or abroad.

The first stylistic changes are discernible from about 1811. There is a slightly different feel in the stripe of the pattern below, and as Ackermann’s Repository informs us, that gauze was becoming a very fashionable material.

Sample from a silk weaver’s pattern book, from the firm of Jourdain and John, Ham, Spitalfields, ca. 1811.

Size: 6.3 cm (2.5 inches) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

From 1816 the first tentative revival of interest in texture for nearly forty years becomes evident, which is illustrated in the pattern below.

Sample from a silk weaver’s pattern book, probably from the firm of Jourdain and John, Ham, Spitalfields, ca. 1816.

Figured satins.

Size: 10.8 cm (4.25 inches) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

The patterns of these years were still, however, the stripes of the 1790s, with a plain stripe alternating with a figured one of equal width – containing once more a floral motif. The shadow effects seen in the pattern below were new.

Sample from a silk weaver’s pattern book, probably from the firm of Jourdain and John, Ham, Spitalfields, ca. 1822.

Figured satins.

Size: 13.3 cm (5.25 inches) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

The sample given below dating from 1825 could have been the beginning of a new era, for this is one of the earliest surviving English jacquard-woven material.

Sample from a silk weaver’s pattern book, Spitalfields, ca. 1825.

Jacquard woven; one of the earliest dated sample of English jacquard woven material.

Size: 5.7 cm (2.25 inches) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Unfortunately for the silk industry, the revival in the demand for pattern silks came too late for the industry to survive in England.

Reference:

[1] The Victoria & Albert Museum Textile Collection, N. Rothstein, Canopy Books, Paris (1994).

For your convenience I have listed below other post in this series:

Silk Designs of the 18th Century

Woven Textile Designs In Britain (1750 to 1763)

Woven Textile Designs in Britain (1764 to 1789)

Woven Textile Designs in Britain (1790 to 1825)

19th Century Silk Shawls from Spitalfields

Silk Designs of Joseph Dandridge

Silk Designs of James Leman

Silk Designs of Christopher Baudouin

Introduction

There are a number of publications featuring the textile design collection held in the Victoria and Albert museum. Recently, Natalie Rothstein’s research into eighteenth century woven textile designs has resulted in a major publication. The images and information contained in this post have been procured from her great book – The Victoria & Albert Museums Textile Collection, N. Rothstein, Canopy Books, Paris (1994). Her research into the collection is comprehensive and insightful. The images and her analysis have been reproduced below.

Woven Textiles in Britain (1790 to 1825)[1]

The two decades from 1790 to 1810 were the worst that the European silk industry had experienced. Clearly the French revolution, which resulted in the loss of the French Court and so the loss in demand for finery in clothing, was certainly a factor, albeit not “the” factor. In fact, it was the devastating change in fashion modes that was the real determinant, which resulted in a dramatic slump in demand for silk clothing.

The slump hit London in 1792 when once more public subscriptions lists were opened for starving journeymen. The “throwsers” felt it in the following year when orders failed to come from London. Such a downturn was not evidenced from pattern books, since the master weavers had to prepare patterns for every season irrespective of the economic conditions. To complicate matters, England suffered a general economic recession, after which there was a slow recovery that lasted until the end of the century. Note: Silk throwing is the industrial process where silk that has been reeled into skeins, is cleaned, receives a twist and is wound onto bobbins. The people who do this are called “throwsers”.

From 1790 to 1797 pattern materials were still woven, although they were inferior in scope or originality compared to those from 1700 to 1770. From that period until 1805 there were hardly any patterns on fashionable silks, or on muslins, which had replaced them.

The dark grounds - popular in the 1780s - continued in popularity early in the 1790s, with colors such as Etruscan red and black being the order of the day, often graced with pseudo-Classical patterns. Fashionable ladies and men wore these as dresses and waistcoats, respectively. The lack of interest in woven patterns generally resulted in designs that were no longer needing to be developed season by season. In this period the beginnings of historicism is evident, which plagued British textile designs ever since.

Compare the two patterns below. Apart from skirt flounces, there was little opportunity for the designer. Also the styles in France and England continued to be the same. For example, Barbara Johnson has a dress like the pattern below, which she noted was French.

Sample from a silk weaver’s pattern book, Harvey, Ham & Perigal, Spitalfields, 1786.

Figured Satin.

Size: 23.5 cm (9.25 inches) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Sample from a silk weaver’s pattern book, Jourdain and John Ham, Spitalfields, 1802.

All woven with metal thread.

Size: 8.9 cm (3.5 inches).

Courtesy of reference[1].

The Neo-Classical motifs continued to be architectural. For example, the rosettes below would not have been out of place if they were mouldings around a door-frame.

Sample from a silk weaver’s pattern book, Harvey, Ham & Perigal, Spitalfields, Winter 1790.

Striped and figured satins.

Size: 13.3 cm (5.25 inches) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Public imagination was fired by campaigns in Egypt and so patterns contained pyramids and palms (see pattern below), but nothing as adventurous as the pseudo-Egyptian hieroglyphics, which were converted by Duddings in the early 19th Century into designs suitable for cotton furniture.

Sample from a silk weaver’s pattern book, probably from the firm of Jourdain and John, Ham, Spitalfields, ca. 1790-94.

Striped and figured satin.

Size: 30.5 cm (12 inches) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Chiné materials in bold colors, such as the yellow and black of the pattern below, were clearly very fashionable.

Sample from a silk weaver’s pattern book, probably from the firm of Jourdain and John, Ham, Spitalfields, ca. 1790-94.

Striped and figured satin.

Size: 20.3 cm (8 inches) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

The conjunction of several colorways, as in the pattern below, makes the effect even more startling.

Sample from a silk weaver’s pattern book, Harvey, Ham & Perigal, Spitalfields, Winter 1790. Striped and figured satin.

Size: 17.8 cm (7 inches) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

By the end of the century all that remain were little patterns (see below) and these hardly changed for the next twenty years.

Sample from a silk weaver’s pattern book, probably from the firm of Jourdain and John, Ham, Spitalfields, ca. 1798-99.

Size: 29.2 cm (11.5 inches) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Certain motifs appeared consistently. For example, the leopard spot was very popular.

Sample from a silk weaver’s pattern book intended for waistcoats, Maze & Steer, Spitalfields, 1786.

Figured satins.

Size: 8.2 cm (3.25 inches) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Another perennial is the fan of plates.

Sample from a silk weaver’s pattern book, probably from the firm of Jourdain and John, Ham, Spitalfields, ca. 1792-94.

Striped and figured satins.

Size: 25.4 cm (10 inches) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

From the period between 1795-1800 there was no major change in style. Even when a pattern such as that given below was repeated, it was not transformed or combined with some other motif, but simply turned on its side. The one style new to silk – Strawberry Hill Gothick – started as an almost invisible device in a self-colored pattern of about 1798. This was not the way new trends had started in the past. From Heideloff’s Gallery of Fashion, which started in 1794, it was only too evident that the fashionable world was wearing linen or cotton and using silk chiefly in ribbons for millinery. Dresses used decreasing amounts of silk materials – 10 yards of silk compared with 14 of a sack-back, while light weight satins and sarcenets used intrinsically less silk, since they were more loosely woven. Only ribbons and shawls remained and many of the latter were plain, edged with embroidery or imported from Kashmir.

From 1800 until about 1810 silks were lightweight, pale and most plain. Only the ribbons woven in Coventry have lively patterns. When there were any patterns on dress silks they tended to be small, self-colored, isolated sprigs very similar to those of the 1790s. Although the jacquard mechanism was invented in 1801, the first attempts to use it in England were not made until 1820-25, for these small patterns on silk seldom needed a draw loom, let alone its more expensive successor. The years from 1810 to 1825 were prosperous for Spitalfields. The industry was largely unaffected by distress and discontent which followed the end of the Napoleonic wars, for the journey men were protected by the Spitalfields Acts and the industry was not yet facing fierce competition from other centers in England or abroad.

The first stylistic changes are discernible from about 1811. There is a slightly different feel in the stripe of the pattern below, and as Ackermann’s Repository informs us, that gauze was becoming a very fashionable material.

Sample from a silk weaver’s pattern book, from the firm of Jourdain and John, Ham, Spitalfields, ca. 1811.

Size: 6.3 cm (2.5 inches) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

From 1816 the first tentative revival of interest in texture for nearly forty years becomes evident, which is illustrated in the pattern below.

Sample from a silk weaver’s pattern book, probably from the firm of Jourdain and John, Ham, Spitalfields, ca. 1816.

Figured satins.

Size: 10.8 cm (4.25 inches) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

The patterns of these years were still, however, the stripes of the 1790s, with a plain stripe alternating with a figured one of equal width – containing once more a floral motif. The shadow effects seen in the pattern below were new.

Sample from a silk weaver’s pattern book, probably from the firm of Jourdain and John, Ham, Spitalfields, ca. 1822.

Figured satins.

Size: 13.3 cm (5.25 inches) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

The sample given below dating from 1825 could have been the beginning of a new era, for this is one of the earliest surviving English jacquard-woven material.

Sample from a silk weaver’s pattern book, Spitalfields, ca. 1825.

Jacquard woven; one of the earliest dated sample of English jacquard woven material.

Size: 5.7 cm (2.25 inches) high.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Unfortunately for the silk industry, the revival in the demand for pattern silks came too late for the industry to survive in England.

Reference:

[1] The Victoria & Albert Museum Textile Collection, N. Rothstein, Canopy Books, Paris (1994).

No comments:

Post a Comment