Preamble

For your convenience I have listed other posts in this series below:

Chinese Calligraphy

European Illumination - Celtic Style

European Illumination - Gothic Style

European Illumination - Romanesque Style

European Illumination - Renaissance Style

The Illumination Art of South-East Asia [1]

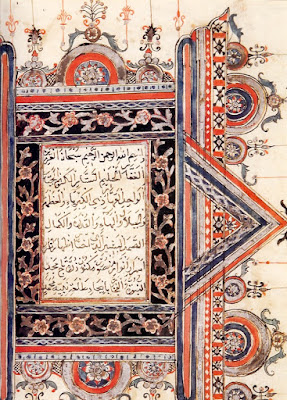

Calligraphy is esteemed as the highest form of all Islamic arts, since its prestige derives from its role as the vehicle for the Divine revelation contained in the Qur'an. Throughout the world Arabic script is seen as the symbol of Islam, serving to unite Muslims in a way that no other script does for any creed.

Qur'an 19th Century (detail).

Banten, Java, Indonesia.

National Library of Indonesia, Jakarta.

The associated art of illumination has never attracted and retained quite the same level of attention, even when charged with the noble task of beautifying copies of the Qur'an. Yet in view of advantages that paper and pen offer to the artist in the creation of abstract designs it has been suggested that illumination is a kind of "mother art" to other Islamic art forms, responsible for the most highly developed manifestation of patterns and design principles, which later found their way on to pottery, stone, metal, textiles and carpets.

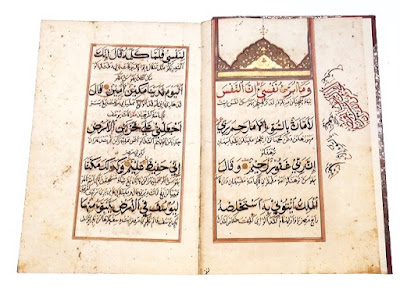

Qur'an 19th Century (detail).

Kitab Mawild, Indonesia.

National Library of Indonesia, Jakarta.

Islamic manuscript art from South-East Asia is still barely known either as a subset of Islamic art or as a distinctive South-East Asian art form. This is largely because, in the Malay world, the study of manuscripts has traditionally been the domain of philologists rather than art historians. It also reflects the uniquely private nature of manuscript art. Textiles and jewelery could be worn; ceramics were used as receptacles; wood carving formed an integral part of architectural structures in mosques, palaces and the houses of nobles; and finely carved tombstones (masonry) heralded the transience of earthly life. Hidden in the covers of manuscript volumes, illumination was only ever encountered and savoured by a very small elite - the readers, owners or patrons of the book.

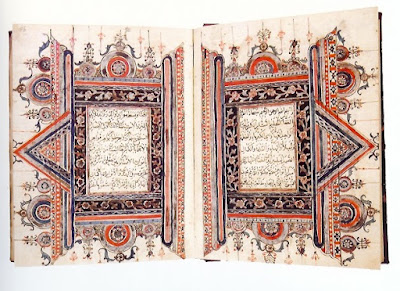

Below are the decorated frames marking the start of the 24th juz' of the Qur'an, chapter al-Zumar 39:32.

Aceh, North Sumatra, Qur'an 1841, National Library of Indonesia, Jakarta.

Aceh, North Sumatra, Qur'an 1841, National Library of Indonesia, Jakarta.

The number of surviving manuscripts illuminated in the Acehnese style runs into hundreds, and one of the finest is a Qur'an held in the National Library of Indonesia dated 1841 (see above image). An exceptional feature of this Qur'an is that each juz' is marked not merely with a marginal ornament, but with a full decorated double-page frame with elaborate corner pieces and a vertical calligraphic panel containing the juz' number, almost modernist in its dramatic angular presentation (see above two images). The Acehnese style exudes vigour, boldness and a robust graphic sensibility rooted in an unwavering sense of regional identity.

A completely different set of aesthetic attributes is evoked by the manuscript art of the North-East coast of the Malay peninsula. Here, in the present-day Malaysian states of Terengganu and Kelantan, and the Southern Thai region of Patani, magnificent examples of Islamic illumination in South-East Asia can be found, with designs of beauty and refinement, realized with craftsmanship of unsurpassed delicacy and breathtaking technique. The manuscript art of this region undoubtedly forms an integrated whole, but at the same time two distinct styles are evident within this East Coast School, one associated with Terengganu and the other with Patani.

East coast of the Malay peninsula, probably Patani, Thailand, Dala'il al-Khayrat.

19th Century.

National Library of Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur.

Terengganu or Kelantan, Malaysia, 'Aqidat al-awamm.

Terengganu style.

Late 19th Century.

National Library of Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur.

The Sulawesi school has a very distinctive style of illuminated double frame (see below). In these frames, the text blocks on each of two facing pages are flanked by decorative vertical borders of the same height. These three vertical sections are in turn closed above and below by a series of densely layered concentric rectangular borders around calligraphic panels containing the surah headings, the whole composition being flanked on both sides by extended vertical borders. At the top and bottom, emerging from the rectangular panels, is a large semi- or partial circle with a smaller circle on either side, while from each of the outer vertical borders protrudes a triangular arch, flanked by two smaller pyramidal composition of three circles.

Sulawesi School - Qur'an February 1731.

Probably Ternate, North Maluku, Indonesia.

National Library of Indonesia, Jakarta.

Sulawesi School - Qur'an 19th Century.

Kitab Mawlid, Indonesia.

National Library of Indonesia, Jakarta.

Qur'an 19th Century.

Kitab Mawlid, Indonesia.

National Library of Indonesia, Jakarta.

The situation in Banten, situated on the Western end of Java and site of a famous Islamic kingdom founded in the late 16th Century, is rather different. Only a few illuminated manuscripts have been documented and they are linked by such common factors as: technical excellence, unusual color schemes and influence from other Islamic manuscript traditions.

Qur'an 19th Century.

Banten, Java, Indonesia.

National Library of Indonesia, Jakarta.

Qur'an, late 18th Century.

Banten Java, Indonesia.

National Library of Indonesia, Jakarta.

The triangle-rectangle structure can be seen in a very interesting Qur'an dated 1856, now held in Sumedang, near Criebon, in West Java. As is usual in Qur'ans from Java, illuminated double frames in the middle if the book are located at the beginning of Surat al-Kahf (18:1). The ornamentation of the triangular arches and rectangular borders is purely calligraphic, with portions of Muslim affirmation of faith, the shahadah, reserved in white against red or blue backgrounds.

Qur'an 1856.

Sumedang, West Java, Indonesia.

Collection of Prabu Geusan Ulun Museum, Sumedang.

All paths in Javanese manuscript art lead to Yogyakarta, where at the court of the Sultan and minor princely house of Pakualaman the nineteen century appears to have been a time for blossoming for the art of book production. Not only did this period witness the production of considerable numbers of richly illuminated and illustrated manuscripts, but uniquely in Islamic South-East Asia - and even in Java - some of the protagonists emerged from the shadows, revealing their working methods and technical vocabulary. A key figure was Prince Suryakusums (1822 - ca.1886), the youngest son of Sultan Hamengkubiwana IV of Yogykarta, who is linked with several manuals on Javanese manuscript illumination filled with examples of decorated frames and accompanying explanatory text on the significance of every constituent component of decoration.

Qur'an Serat Tajussalatin, 1799 - 1851.

Yogyakarta, Central Java, Indonesia.

Museum Sonobudoyo, Yogyakarta.

I love these art forms. As a scholar of traditional Art of South-East Asia, please enjoy it with me, even though my Art is modern, and Australian, as well as a depiction of art that is environmentally sensitive. My regional cultural heritage has always informed my Art!

Love the experience!

Marie-Therese Wisniowski.

Reference:

[1] A. T. Gallop, Chapter 5: Islamic Manuscript Art of South-East Asia, Crescent Moon, Gordon-Daring Foundation (2005).

For your convenience I have listed other posts in this series below:

Chinese Calligraphy

European Illumination - Celtic Style

European Illumination - Gothic Style

European Illumination - Romanesque Style

European Illumination - Renaissance Style

The Illumination Art of South-East Asia [1]

Calligraphy is esteemed as the highest form of all Islamic arts, since its prestige derives from its role as the vehicle for the Divine revelation contained in the Qur'an. Throughout the world Arabic script is seen as the symbol of Islam, serving to unite Muslims in a way that no other script does for any creed.

Qur'an 19th Century (detail).

Banten, Java, Indonesia.

National Library of Indonesia, Jakarta.

The associated art of illumination has never attracted and retained quite the same level of attention, even when charged with the noble task of beautifying copies of the Qur'an. Yet in view of advantages that paper and pen offer to the artist in the creation of abstract designs it has been suggested that illumination is a kind of "mother art" to other Islamic art forms, responsible for the most highly developed manifestation of patterns and design principles, which later found their way on to pottery, stone, metal, textiles and carpets.

Qur'an 19th Century (detail).

Kitab Mawild, Indonesia.

National Library of Indonesia, Jakarta.

Islamic manuscript art from South-East Asia is still barely known either as a subset of Islamic art or as a distinctive South-East Asian art form. This is largely because, in the Malay world, the study of manuscripts has traditionally been the domain of philologists rather than art historians. It also reflects the uniquely private nature of manuscript art. Textiles and jewelery could be worn; ceramics were used as receptacles; wood carving formed an integral part of architectural structures in mosques, palaces and the houses of nobles; and finely carved tombstones (masonry) heralded the transience of earthly life. Hidden in the covers of manuscript volumes, illumination was only ever encountered and savoured by a very small elite - the readers, owners or patrons of the book.

Below are the decorated frames marking the start of the 24th juz' of the Qur'an, chapter al-Zumar 39:32.

Aceh, North Sumatra, Qur'an 1841, National Library of Indonesia, Jakarta.

Aceh, North Sumatra, Qur'an 1841, National Library of Indonesia, Jakarta.

The number of surviving manuscripts illuminated in the Acehnese style runs into hundreds, and one of the finest is a Qur'an held in the National Library of Indonesia dated 1841 (see above image). An exceptional feature of this Qur'an is that each juz' is marked not merely with a marginal ornament, but with a full decorated double-page frame with elaborate corner pieces and a vertical calligraphic panel containing the juz' number, almost modernist in its dramatic angular presentation (see above two images). The Acehnese style exudes vigour, boldness and a robust graphic sensibility rooted in an unwavering sense of regional identity.

A completely different set of aesthetic attributes is evoked by the manuscript art of the North-East coast of the Malay peninsula. Here, in the present-day Malaysian states of Terengganu and Kelantan, and the Southern Thai region of Patani, magnificent examples of Islamic illumination in South-East Asia can be found, with designs of beauty and refinement, realized with craftsmanship of unsurpassed delicacy and breathtaking technique. The manuscript art of this region undoubtedly forms an integrated whole, but at the same time two distinct styles are evident within this East Coast School, one associated with Terengganu and the other with Patani.

East coast of the Malay peninsula, probably Patani, Thailand, Dala'il al-Khayrat.

19th Century.

National Library of Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur.

Terengganu or Kelantan, Malaysia, 'Aqidat al-awamm.

Terengganu style.

Late 19th Century.

National Library of Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur.

The Sulawesi school has a very distinctive style of illuminated double frame (see below). In these frames, the text blocks on each of two facing pages are flanked by decorative vertical borders of the same height. These three vertical sections are in turn closed above and below by a series of densely layered concentric rectangular borders around calligraphic panels containing the surah headings, the whole composition being flanked on both sides by extended vertical borders. At the top and bottom, emerging from the rectangular panels, is a large semi- or partial circle with a smaller circle on either side, while from each of the outer vertical borders protrudes a triangular arch, flanked by two smaller pyramidal composition of three circles.

Sulawesi School - Qur'an February 1731.

Probably Ternate, North Maluku, Indonesia.

National Library of Indonesia, Jakarta.

Sulawesi School - Qur'an 19th Century.

Kitab Mawlid, Indonesia.

National Library of Indonesia, Jakarta.

Qur'an 19th Century.

Kitab Mawlid, Indonesia.

National Library of Indonesia, Jakarta.

The situation in Banten, situated on the Western end of Java and site of a famous Islamic kingdom founded in the late 16th Century, is rather different. Only a few illuminated manuscripts have been documented and they are linked by such common factors as: technical excellence, unusual color schemes and influence from other Islamic manuscript traditions.

Qur'an 19th Century.

Banten, Java, Indonesia.

National Library of Indonesia, Jakarta.

Qur'an, late 18th Century.

Banten Java, Indonesia.

National Library of Indonesia, Jakarta.

The triangle-rectangle structure can be seen in a very interesting Qur'an dated 1856, now held in Sumedang, near Criebon, in West Java. As is usual in Qur'ans from Java, illuminated double frames in the middle if the book are located at the beginning of Surat al-Kahf (18:1). The ornamentation of the triangular arches and rectangular borders is purely calligraphic, with portions of Muslim affirmation of faith, the shahadah, reserved in white against red or blue backgrounds.

Qur'an 1856.

Sumedang, West Java, Indonesia.

Collection of Prabu Geusan Ulun Museum, Sumedang.

All paths in Javanese manuscript art lead to Yogyakarta, where at the court of the Sultan and minor princely house of Pakualaman the nineteen century appears to have been a time for blossoming for the art of book production. Not only did this period witness the production of considerable numbers of richly illuminated and illustrated manuscripts, but uniquely in Islamic South-East Asia - and even in Java - some of the protagonists emerged from the shadows, revealing their working methods and technical vocabulary. A key figure was Prince Suryakusums (1822 - ca.1886), the youngest son of Sultan Hamengkubiwana IV of Yogykarta, who is linked with several manuals on Javanese manuscript illumination filled with examples of decorated frames and accompanying explanatory text on the significance of every constituent component of decoration.

Qur'an Serat Tajussalatin, 1799 - 1851.

Yogyakarta, Central Java, Indonesia.

Museum Sonobudoyo, Yogyakarta.

I love these art forms. As a scholar of traditional Art of South-East Asia, please enjoy it with me, even though my Art is modern, and Australian, as well as a depiction of art that is environmentally sensitive. My regional cultural heritage has always informed my Art!

Love the experience!

Marie-Therese Wisniowski.

Reference:

[1] A. T. Gallop, Chapter 5: Islamic Manuscript Art of South-East Asia, Crescent Moon, Gordon-Daring Foundation (2005).

No comments:

Post a Comment