Preamble

For your convenience I have listed below other posts in this series:

Diversity of African Textiles

African Textiles: West Africa

Stripweaves (West Africa) - Part I

Stripweaves (West Africa) - Part II

Stripweaves (West Africa) - Part III

Stripweaves (West Africa) - Part IV

Djerma Weaving of Niger and Burkina-Faso

Woolen Stripweaves of the Niger Bend

Nigerian Horizontal - Loom Weaving

Yoruba Lace Weave

Nigerian Women's Vertical Looms

The Supplementary Weft Cloths of Ijebu-Ode and Akwete

African Tie and Dye

Tie and Dye of the Dida, Ivory Coast

African Stitch Resist

Yoruba Stitch Resist

Yoruba: Machine-Stitched Resist Indigo-Dyed Cloth

Yoruba and Baulé Warp Ikat

Nigerian Starch-Resist (by hand)

Stencilled Starch-Resist

Wax Resistbr /> Mali Mud Cloths

Nigerian Horizontal - Loom Weaving [1]

Men weaving on the horizontal, double heddle treadle loom can be found in many parts of Nigeria. Two of the most important traditions are those of the Yoruba and the Hausa. According to recent research by textile scholar Duncan Clarke, there were approximately 15,000 weavers working on the horizontal narrow loom in Yorubaland in 2003.

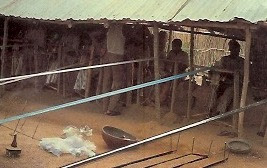

Yoruba stripweavers in their shed, Iseyin, South-West Nigeria.

They mainly produce women's cloths, aso oke, for which there is great demand in Ilorin and Iseyin. At weddings, the bride's and groom's party, each wear different sets of aso oke in particular colors to distinguish one from another. Both parties can use up to fifty mainly new cloths - a steady demand for the weavers' wares. Those who cannot afford new cloth will wear a similarly colored cloth if they have one.

Prestige cloth formerly woven by men in strips at Owo in Yorubaland, a great center of weaving. Known as elegheghe papa it incorporates red in the tapestry design and a lizard motif at the end of each strip.

The weavers work under a master weaver in his compound, up to ten weavers sitting side by side in the shade. The warps are tied to a drag stone mounted on wooden sledges stretched out in front of them. Until very recently, the weavers were male and apprenticed on payment of a fee for a number of years until they learned the trade (if they were immediate family, the fee was waived).

Prestige cloth woven by men in ther Benue valley, possibly by the Jukun, central eastern Nigeria. Each alternate strip incorporates motifs worked in the very rare supplementary-warp technique.

Most of the oso oke weavers are therefore boys aged between eight and fifteen years of age, who receive food, but no wages. Clarke states that in the normal course of events, these boys stop weaving and go on to forge another career, only to return to the textile business as master weavers when they have amassed sufficient capital.

A recent phenomenon is the introduction of female apprentices, who are taken on under the same terms as the boys, but at a slightly older age. The difference is that they tend to stay in the weaving business and set up as master weavers as soon as they can after serving their apprenticeship. They recruit fresh apprentices, who are often girls. In this way the traditional barriers between the two sexes and their spheres of work are gradually being broken down.

Aso oke stripwoven woman's warp, Ilorin. Each alternate strip incorporates weft-float motifs worked in imported silk. Koran boards are a popular motif.

Hausa weavers are to be found all over northern Nigeria. Different catagories of looms are used to weave different widths and quality of cloth. The Hausa weave the narrowist of strips turkudi (2.5 cm; one inch) and the widest (45-70 cm; 18 inches) in West Africa. The former is used to make the highly valued Tuareg veils and the latter is so wide that it is often confused with the products of the women's upright loom.

Woman's wrap woven on the Hausa horizontal loom, Sokoto, nothern Nigeria.

Yoruba weavers weave on a narrow-frame loom of carpentered parts very similar to those of the Ashanti and the Ewe. The basic system and framework of the loom is very similar to that of the Ghanaian weavers, but Nigerian weavers do not use twin pairs of heddles to alternate blocks of weft-face weaving in the same strip. The Yoruba employ a single pair of heddles and extra string heddles for floats. Yoruba aso oke are very varied in composition. One popular pattern involves weaving one long warp-striped strip. The other strip is woven in white cotton in plain weave.

Luru cotton stripwoven blanket woven by Hausa weaver in or around Kano.

All along this strip, motifs are introduced in floating weft. Recurring motifs are in an arrow surmounting a square, which symbolizes the Koran boards on which young boys learn to read and write. Red silk, called al-hareen, originally Tunisian, is the preferred thread for floating weft motifs, although black cotton is often used. Women's cloths are formed by cutting these two strips up into appropriate lengths and then sewing them, selvedge to selvedge, in alternate strips.

The Hausa loom is very portable, with the heddle and beater suspended from above and behind the weaver fixed to a wall or tree. The weaver, who sits on the ground with feet outstretched, operates the pedals that open and shut the shed. The warp is tensioned in the usual way, but the finished web is wound around a cloth beam below his legs.

Reference:

[1] J. Gillow, African Textiles, Thames & Hudson Ltd, London (2003).

For your convenience I have listed below other posts in this series:

Diversity of African Textiles

African Textiles: West Africa

Stripweaves (West Africa) - Part I

Stripweaves (West Africa) - Part II

Stripweaves (West Africa) - Part III

Stripweaves (West Africa) - Part IV

Djerma Weaving of Niger and Burkina-Faso

Woolen Stripweaves of the Niger Bend

Nigerian Horizontal - Loom Weaving

Yoruba Lace Weave

Nigerian Women's Vertical Looms

The Supplementary Weft Cloths of Ijebu-Ode and Akwete

African Tie and Dye

Tie and Dye of the Dida, Ivory Coast

African Stitch Resist

Yoruba Stitch Resist

Yoruba: Machine-Stitched Resist Indigo-Dyed Cloth

Yoruba and Baulé Warp Ikat

Nigerian Starch-Resist (by hand)

Stencilled Starch-Resist

Wax Resistbr /> Mali Mud Cloths

Nigerian Horizontal - Loom Weaving [1]

Men weaving on the horizontal, double heddle treadle loom can be found in many parts of Nigeria. Two of the most important traditions are those of the Yoruba and the Hausa. According to recent research by textile scholar Duncan Clarke, there were approximately 15,000 weavers working on the horizontal narrow loom in Yorubaland in 2003.

Yoruba stripweavers in their shed, Iseyin, South-West Nigeria.

They mainly produce women's cloths, aso oke, for which there is great demand in Ilorin and Iseyin. At weddings, the bride's and groom's party, each wear different sets of aso oke in particular colors to distinguish one from another. Both parties can use up to fifty mainly new cloths - a steady demand for the weavers' wares. Those who cannot afford new cloth will wear a similarly colored cloth if they have one.

Prestige cloth formerly woven by men in strips at Owo in Yorubaland, a great center of weaving. Known as elegheghe papa it incorporates red in the tapestry design and a lizard motif at the end of each strip.

The weavers work under a master weaver in his compound, up to ten weavers sitting side by side in the shade. The warps are tied to a drag stone mounted on wooden sledges stretched out in front of them. Until very recently, the weavers were male and apprenticed on payment of a fee for a number of years until they learned the trade (if they were immediate family, the fee was waived).

Prestige cloth woven by men in ther Benue valley, possibly by the Jukun, central eastern Nigeria. Each alternate strip incorporates motifs worked in the very rare supplementary-warp technique.

Most of the oso oke weavers are therefore boys aged between eight and fifteen years of age, who receive food, but no wages. Clarke states that in the normal course of events, these boys stop weaving and go on to forge another career, only to return to the textile business as master weavers when they have amassed sufficient capital.

A recent phenomenon is the introduction of female apprentices, who are taken on under the same terms as the boys, but at a slightly older age. The difference is that they tend to stay in the weaving business and set up as master weavers as soon as they can after serving their apprenticeship. They recruit fresh apprentices, who are often girls. In this way the traditional barriers between the two sexes and their spheres of work are gradually being broken down.

Aso oke stripwoven woman's warp, Ilorin. Each alternate strip incorporates weft-float motifs worked in imported silk. Koran boards are a popular motif.

Hausa weavers are to be found all over northern Nigeria. Different catagories of looms are used to weave different widths and quality of cloth. The Hausa weave the narrowist of strips turkudi (2.5 cm; one inch) and the widest (45-70 cm; 18 inches) in West Africa. The former is used to make the highly valued Tuareg veils and the latter is so wide that it is often confused with the products of the women's upright loom.

Woman's wrap woven on the Hausa horizontal loom, Sokoto, nothern Nigeria.

Yoruba weavers weave on a narrow-frame loom of carpentered parts very similar to those of the Ashanti and the Ewe. The basic system and framework of the loom is very similar to that of the Ghanaian weavers, but Nigerian weavers do not use twin pairs of heddles to alternate blocks of weft-face weaving in the same strip. The Yoruba employ a single pair of heddles and extra string heddles for floats. Yoruba aso oke are very varied in composition. One popular pattern involves weaving one long warp-striped strip. The other strip is woven in white cotton in plain weave.

Luru cotton stripwoven blanket woven by Hausa weaver in or around Kano.

All along this strip, motifs are introduced in floating weft. Recurring motifs are in an arrow surmounting a square, which symbolizes the Koran boards on which young boys learn to read and write. Red silk, called al-hareen, originally Tunisian, is the preferred thread for floating weft motifs, although black cotton is often used. Women's cloths are formed by cutting these two strips up into appropriate lengths and then sewing them, selvedge to selvedge, in alternate strips.

The Hausa loom is very portable, with the heddle and beater suspended from above and behind the weaver fixed to a wall or tree. The weaver, who sits on the ground with feet outstretched, operates the pedals that open and shut the shed. The warp is tensioned in the usual way, but the finished web is wound around a cloth beam below his legs.

Reference:

[1] J. Gillow, African Textiles, Thames & Hudson Ltd, London (2003).

No comments:

Post a Comment