Preamble

For your convenience, I have listed below posts that also focus on rugs.

Navajo Rugs

Persian Rugs

Caucasian Rugs

Turkish Rugs

Navajo Rugs of the Ganado, Crystal and Two Grey Hills Region

Navajo Rugs of Chinle, Wide Ruins and Teec Nos Pos Regions

Navajo Rugs of the Western Reservation

Introduction

Rug designs are important with respect to art. They hold a place of pride as floor or wall coverings, but moreover they can also inspire other artwork such as miniature artwork using needlepoint - with no loom in sight! Such miniature rugs have been worked with needle and wool on a needlepoint canvas. Typically the miniature rugs have been worked in Paternayan wool yarn on a #18 canvas, using two different types of needlepoint stitches such as the Continental stitch and the Basketweave stitch [1].

Continental stitch is typically used to make outlines and single rows of design in needlepoint miniature rugs.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Basketweave stitch is used for the larger proportions of the design and background of needlepoint miniature rugs.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Typically the canvas size of needlepoint miniature rugs are larger than the stitched piece; that is, for a 9 x 12 inch miniature rug, the canvas size is 13 x 16 inches with the extra canvas turned under and fastened to the back of the rug when the stitching has been completed.

A needlework miniature rug based on an oriental rug design.

Courtesy of reference[1].

There is an excellent book written on oriental carpets[2] and another written on needlework miniature rugs[1]. Some of the latter have been donated to the Toy & Miniature Museum in Kansas City, Missouri (USA). There are no better books for you to purchase in both areas, respectively.

The post today will not deal with how to create needlework miniature rugs but rather deal with the design of Turkish rugs themselves. Nevertheless, the images of most designs are those reproduced by Frank M. Cooper using his needlepoint techniques[1].

Nomadic Weaving of Carpets

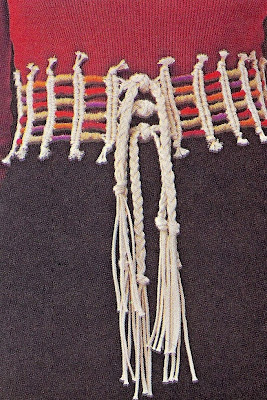

Nomad weavers had all the ingredients needed for rug making. For example, they had access to the design of a vertical loom for which the construction materials – straight branches – were easily obtainable. On a wooden frame, they tightly wound a continuous strand of yarn, from top to bottom, round both the top and bottom beams[1].

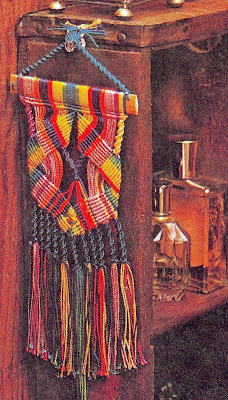

Nomadic weavers create colorful, richly patterned carpets on simple, portable looms, often constructed from long straight tree limbs.

Courtesy of reference[1].

The vertically wound thread is called the warp. In the process of weaving, horizontal threads called weft threads are passed in front of and behind alternate threads. To create the rug pile, the weaver ties yarn around two adjacent vertical warp threads. After a complete row of knots have been tied, the weaver passes a weft thread through the warp threads and, with a comb, pushes the knots and the weft threads down to the bottom of a loom. These continuous weft threads, passing back and forth across the warp, help keep the knots in place and give the rug its body [1].

A modern day weaver working in a rug factory in the Middle East.

Courtesy of reference[1].

The yarn was made from the wool of the weaver’s own sheep. Members of the family or tribe sheared the sheep and then the wool was carded, spun into yarn, and dyed in small vats. Due to the size of the vats, only limited quantities of yarn could be dyed at any point in time, which sometimes would lead to variations in color in the ancient carpets. The dyes were made according to “secret” formulas held for generations by each tribe but basically common threads existed in all dyed rugs; for example, the madder plant was used for reds, indigo for blues, roots of plants, bark of trees, and other natural materials for other colors. The quality of the color was affected by the quality of water (hard or soft) and also by mordants used in the dyeing process[1].

Madder Red: The roots of the madder plant yields the dye used for most red colors. Depending on both the age of the roots and the length of time they are boiled, the range of colors can vary from the deepest of reds to pinks and to purples. The color “red” generally signifies passion and is the color associated with happiness and success.

As early as the thirteenth century, Turkey developed a sea trade with Italy, and rugs depicted in the paintings of that period, notably by those of Italian artist, Lorenzo Lotto, and the German artist, Hans Holbein. Holbein often featured a double-medallion rug design. Rugs with this feature became known as “Holbein Rugs”.

One of Holbein’s paintings featuring a Turkish rug in the foreground.

As a result of trade with Italy and other European countries, the demand for rugs became so great that a cottage industry quickly developed. However, the industry could not keep up with demand and so carpet-weaving workshops were set up in which many rugs could be produced at the same time. Typically an overseer, referring to sketches furnished by the workshop owner, would call out the design and colors to the weaver. Many of the weavers were pre-teen children, who with their supple fingers could tie as many as 10,000 knots a day.

A child weaver in modern day Pakistan.

All of the supplies were furnished by the workshops, and sometimes were provided to the cottage industries as well. No longer were tribal designs and colors used – instead colors and patterns were determined by fashion as is the case in today’s world.

Fashionable modern-day designed carpet.

Turkish Carpets

Turkish carpets were commented on by Marco Polo who wrote about their beauty and artistry in the 13th century. A number of carpets from this period - known as the Seljuk carpets - were discovered in several Mosques in central Anatolia, underneath many layers of subsequently placed carpets. The Seljuk carpets are today in the museums in Konya and Istanbul.

Carpet fragment from Esrefoglu Mosque, Beysehir. Seljuk period, 13th century.

Mosques are considered the common house in a Muslim community. In addition, since the praying ritual requires one to kneel and touch the ground with one’s forehead, the Mosques are covered from wall to wall with several layers of carpets contributed by the faithful as an act of piety.

Alaeddin inside Aslanapa.

The art of weaving was introduced to Anatolia by the Seljuks toward the end of the 11th and the beginning of 12th centuries when Seljuk sovereignty was at its height. In addition to numerous carpet fragments, many of which are yet to be documented, there are 18 carpets and fragments, which are known to be of Seljuk origin. The technical aspects and vast variety of designs used proves the resourcefulness and the splendor of Seljuk rug weaving. The oldest surviving Seljuk carpets are dated from the 13th to 14th centuries. Eight of these carpets were discovered in the Alaeddin Mosque in Konya (capital of Anatolian Seljuks) in 1905 by Loytred, a member of German consulate staff, and were woven at some time between the years 1220 and 1250 - at the pinnacle of Seljuks reign.

Modern-day Turkey

When the Seljuks of Turkestan overran the Near East in the eleventh century, they captured the city of Konya. They established one of their Sultanates there, which became known for its opulence and culture. In recent years, these rugs were sought after and so the Vakiflar Hali Muzesi in Istanbul collected and saved many of the rugs from Konya for prosperity[1].

Cooper’s miniature needlepoint rug based on a Konya rug held in the collection of the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art (Istanbul, Turkey).

Courtesy of reference[1].

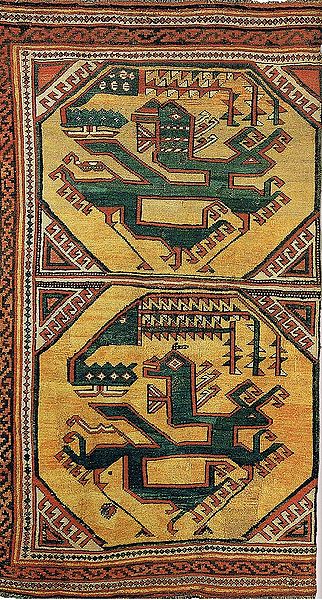

The Anatolian rug (see below) uses a dragon and phoenix design. It can be dated from the fifteen century. A very similar design is depicted in a fresco by Domenico di Bartolo, entitled “The Wedding of the Foundlings” (dated 1440 and 1444)[1].

Wilhelm von Bode, a German scholar, found the rug in Italy and acquired it in 1886. It now hangs in Berlin Museum. The subject matter and the yellow background suggest a Chinese influence. It measures 35 x 38 inches [1].

Anatolian Berlin Rug.

Collection: Berlin: Museum fur Islamische Kunst.

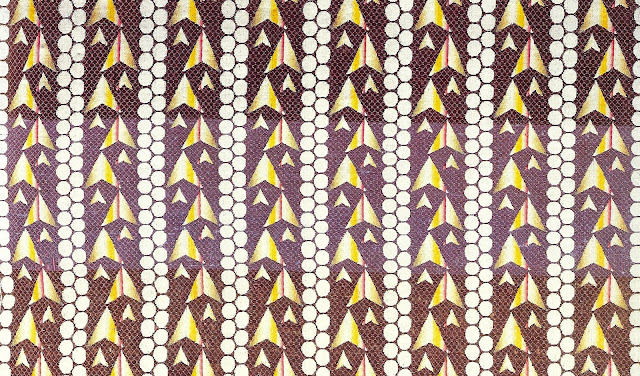

Cooper’s needlepoint miniature rug of the Anatolian Berlin Rug (see above).

Courtesy reference[1]. Note: Cooper substituted brown in place of blue stripes and added a right border.

Mudjar is a town in Turkey. The colors of their rugs are more varied than those of Anatolian origin. This design has colors of mauve, pink, blue, green and shades of yellow, which are usually not found in other rugs from even this area. The original rug dates from the first part of the nineteenth century and is in a private collection. The original rug measures 42.25 x 59.75 inches[1].

Cooper’s needlework miniature rug version adapted from an illustration in the book “Oriental Carpets” by Ulrich Schurmann [2].

Courtesy of reference[1].

In the Western part of Turkey, almost on the Aegean Sea, there is a small city called Bergama. The image of the rug below appears in a painting by Hans Memling, a fifteenth-century Flemish painter. The painting is now in the collection of Baron Thyssen-Bornemisza. There is no assurance that this is a Bergama rug, but it is consistent with the designs of rugs from that region[1].

Cooper’s needlepoint miniature rug version of Bornemisza’s Bergama rug.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Romans, Persian, Greek and other civilizations conquered the Turkish city of Bergama. Although nearly destroyed during the Turkish Wars, today it is a city of almost 20,000 people.

The rugs made in Bergama are usually almost square, with one or two medallions occupying the center field. These medallions are sometimes defined very clearly by surrounding lines of white or ivory. Although the reasons are not understood, the bold designs of these rugs are similar to Caucasian rugs rather than being similar to other Turkish rugs[1].

Cooper’s needlepoint miniature rug version of a rug that dates from 1800 and illustrated in “Oriental Carpets” by Ulrich Schurmann[2]. The original rug measures 56 x 72 inches. Cooper added the archaic S-forms in the border of the above needlepoint miniature rug.

Ushak rug (see below) was listed in “Oriental Carpets”[2] as a seventeenth century rug. Wilhelm von Bode argued it should be placed ahead of all other Ushak prayer rugs, some of which are known to be from the sixteenth century. The rug is in the collection of the Islamic Museum in Berlin.

Cooper’s needlepoint miniature rug version of an Ushak rug. In the original design the outer border was chartered red and gold, but Cooper changed it to red and white in his depiction.

Postscript

Today marks the 100th anniversary of the Anzac (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) landing on the Gallipoli peninsula (Turkey) in 1915 (World War I). It is the day on which Australians and New Zealanders reflect on those who served their respective countries and died in all wars, conflicts, and peacekeeping operations. The spirit of Anzac, with its human qualities of courage, mateship, and sacrifice, continues to have meaning and relevance to a sense of national identity for citizens of these two countries - "Lest we forget".

References:

[1] F. M. Cooper, Oriental Carpets in Miniature, Interweave Press, Colorado (1994).

[2] Ulrich Schurmann, Oriental Carpets, Hamlyn Publishing, London (1966).

For your convenience, I have listed below posts that also focus on rugs.

Navajo Rugs

Persian Rugs

Caucasian Rugs

Turkish Rugs

Navajo Rugs of the Ganado, Crystal and Two Grey Hills Region

Navajo Rugs of Chinle, Wide Ruins and Teec Nos Pos Regions

Navajo Rugs of the Western Reservation

Introduction

Rug designs are important with respect to art. They hold a place of pride as floor or wall coverings, but moreover they can also inspire other artwork such as miniature artwork using needlepoint - with no loom in sight! Such miniature rugs have been worked with needle and wool on a needlepoint canvas. Typically the miniature rugs have been worked in Paternayan wool yarn on a #18 canvas, using two different types of needlepoint stitches such as the Continental stitch and the Basketweave stitch [1].

Continental stitch is typically used to make outlines and single rows of design in needlepoint miniature rugs.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Basketweave stitch is used for the larger proportions of the design and background of needlepoint miniature rugs.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Typically the canvas size of needlepoint miniature rugs are larger than the stitched piece; that is, for a 9 x 12 inch miniature rug, the canvas size is 13 x 16 inches with the extra canvas turned under and fastened to the back of the rug when the stitching has been completed.

A needlework miniature rug based on an oriental rug design.

Courtesy of reference[1].

There is an excellent book written on oriental carpets[2] and another written on needlework miniature rugs[1]. Some of the latter have been donated to the Toy & Miniature Museum in Kansas City, Missouri (USA). There are no better books for you to purchase in both areas, respectively.

The post today will not deal with how to create needlework miniature rugs but rather deal with the design of Turkish rugs themselves. Nevertheless, the images of most designs are those reproduced by Frank M. Cooper using his needlepoint techniques[1].

Nomadic Weaving of Carpets

Nomad weavers had all the ingredients needed for rug making. For example, they had access to the design of a vertical loom for which the construction materials – straight branches – were easily obtainable. On a wooden frame, they tightly wound a continuous strand of yarn, from top to bottom, round both the top and bottom beams[1].

Nomadic weavers create colorful, richly patterned carpets on simple, portable looms, often constructed from long straight tree limbs.

Courtesy of reference[1].

The vertically wound thread is called the warp. In the process of weaving, horizontal threads called weft threads are passed in front of and behind alternate threads. To create the rug pile, the weaver ties yarn around two adjacent vertical warp threads. After a complete row of knots have been tied, the weaver passes a weft thread through the warp threads and, with a comb, pushes the knots and the weft threads down to the bottom of a loom. These continuous weft threads, passing back and forth across the warp, help keep the knots in place and give the rug its body [1].

A modern day weaver working in a rug factory in the Middle East.

Courtesy of reference[1].

The yarn was made from the wool of the weaver’s own sheep. Members of the family or tribe sheared the sheep and then the wool was carded, spun into yarn, and dyed in small vats. Due to the size of the vats, only limited quantities of yarn could be dyed at any point in time, which sometimes would lead to variations in color in the ancient carpets. The dyes were made according to “secret” formulas held for generations by each tribe but basically common threads existed in all dyed rugs; for example, the madder plant was used for reds, indigo for blues, roots of plants, bark of trees, and other natural materials for other colors. The quality of the color was affected by the quality of water (hard or soft) and also by mordants used in the dyeing process[1].

Madder Red: The roots of the madder plant yields the dye used for most red colors. Depending on both the age of the roots and the length of time they are boiled, the range of colors can vary from the deepest of reds to pinks and to purples. The color “red” generally signifies passion and is the color associated with happiness and success.

As early as the thirteenth century, Turkey developed a sea trade with Italy, and rugs depicted in the paintings of that period, notably by those of Italian artist, Lorenzo Lotto, and the German artist, Hans Holbein. Holbein often featured a double-medallion rug design. Rugs with this feature became known as “Holbein Rugs”.

One of Holbein’s paintings featuring a Turkish rug in the foreground.

As a result of trade with Italy and other European countries, the demand for rugs became so great that a cottage industry quickly developed. However, the industry could not keep up with demand and so carpet-weaving workshops were set up in which many rugs could be produced at the same time. Typically an overseer, referring to sketches furnished by the workshop owner, would call out the design and colors to the weaver. Many of the weavers were pre-teen children, who with their supple fingers could tie as many as 10,000 knots a day.

A child weaver in modern day Pakistan.

All of the supplies were furnished by the workshops, and sometimes were provided to the cottage industries as well. No longer were tribal designs and colors used – instead colors and patterns were determined by fashion as is the case in today’s world.

Fashionable modern-day designed carpet.

Turkish Carpets

Turkish carpets were commented on by Marco Polo who wrote about their beauty and artistry in the 13th century. A number of carpets from this period - known as the Seljuk carpets - were discovered in several Mosques in central Anatolia, underneath many layers of subsequently placed carpets. The Seljuk carpets are today in the museums in Konya and Istanbul.

Carpet fragment from Esrefoglu Mosque, Beysehir. Seljuk period, 13th century.

Mosques are considered the common house in a Muslim community. In addition, since the praying ritual requires one to kneel and touch the ground with one’s forehead, the Mosques are covered from wall to wall with several layers of carpets contributed by the faithful as an act of piety.

Alaeddin inside Aslanapa.

The art of weaving was introduced to Anatolia by the Seljuks toward the end of the 11th and the beginning of 12th centuries when Seljuk sovereignty was at its height. In addition to numerous carpet fragments, many of which are yet to be documented, there are 18 carpets and fragments, which are known to be of Seljuk origin. The technical aspects and vast variety of designs used proves the resourcefulness and the splendor of Seljuk rug weaving. The oldest surviving Seljuk carpets are dated from the 13th to 14th centuries. Eight of these carpets were discovered in the Alaeddin Mosque in Konya (capital of Anatolian Seljuks) in 1905 by Loytred, a member of German consulate staff, and were woven at some time between the years 1220 and 1250 - at the pinnacle of Seljuks reign.

Modern-day Turkey

When the Seljuks of Turkestan overran the Near East in the eleventh century, they captured the city of Konya. They established one of their Sultanates there, which became known for its opulence and culture. In recent years, these rugs were sought after and so the Vakiflar Hali Muzesi in Istanbul collected and saved many of the rugs from Konya for prosperity[1].

Cooper’s miniature needlepoint rug based on a Konya rug held in the collection of the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art (Istanbul, Turkey).

Courtesy of reference[1].

The Anatolian rug (see below) uses a dragon and phoenix design. It can be dated from the fifteen century. A very similar design is depicted in a fresco by Domenico di Bartolo, entitled “The Wedding of the Foundlings” (dated 1440 and 1444)[1].

Wilhelm von Bode, a German scholar, found the rug in Italy and acquired it in 1886. It now hangs in Berlin Museum. The subject matter and the yellow background suggest a Chinese influence. It measures 35 x 38 inches [1].

Anatolian Berlin Rug.

Collection: Berlin: Museum fur Islamische Kunst.

Cooper’s needlepoint miniature rug of the Anatolian Berlin Rug (see above).

Courtesy reference[1]. Note: Cooper substituted brown in place of blue stripes and added a right border.

Mudjar is a town in Turkey. The colors of their rugs are more varied than those of Anatolian origin. This design has colors of mauve, pink, blue, green and shades of yellow, which are usually not found in other rugs from even this area. The original rug dates from the first part of the nineteenth century and is in a private collection. The original rug measures 42.25 x 59.75 inches[1].

Cooper’s needlework miniature rug version adapted from an illustration in the book “Oriental Carpets” by Ulrich Schurmann [2].

Courtesy of reference[1].

In the Western part of Turkey, almost on the Aegean Sea, there is a small city called Bergama. The image of the rug below appears in a painting by Hans Memling, a fifteenth-century Flemish painter. The painting is now in the collection of Baron Thyssen-Bornemisza. There is no assurance that this is a Bergama rug, but it is consistent with the designs of rugs from that region[1].

Cooper’s needlepoint miniature rug version of Bornemisza’s Bergama rug.

Courtesy of reference[1].

Romans, Persian, Greek and other civilizations conquered the Turkish city of Bergama. Although nearly destroyed during the Turkish Wars, today it is a city of almost 20,000 people.

The rugs made in Bergama are usually almost square, with one or two medallions occupying the center field. These medallions are sometimes defined very clearly by surrounding lines of white or ivory. Although the reasons are not understood, the bold designs of these rugs are similar to Caucasian rugs rather than being similar to other Turkish rugs[1].

Cooper’s needlepoint miniature rug version of a rug that dates from 1800 and illustrated in “Oriental Carpets” by Ulrich Schurmann[2]. The original rug measures 56 x 72 inches. Cooper added the archaic S-forms in the border of the above needlepoint miniature rug.

Ushak rug (see below) was listed in “Oriental Carpets”[2] as a seventeenth century rug. Wilhelm von Bode argued it should be placed ahead of all other Ushak prayer rugs, some of which are known to be from the sixteenth century. The rug is in the collection of the Islamic Museum in Berlin.

Cooper’s needlepoint miniature rug version of an Ushak rug. In the original design the outer border was chartered red and gold, but Cooper changed it to red and white in his depiction.

Postscript

Today marks the 100th anniversary of the Anzac (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) landing on the Gallipoli peninsula (Turkey) in 1915 (World War I). It is the day on which Australians and New Zealanders reflect on those who served their respective countries and died in all wars, conflicts, and peacekeeping operations. The spirit of Anzac, with its human qualities of courage, mateship, and sacrifice, continues to have meaning and relevance to a sense of national identity for citizens of these two countries - "Lest we forget".

References:

[1] F. M. Cooper, Oriental Carpets in Miniature, Interweave Press, Colorado (1994).

[2] Ulrich Schurmann, Oriental Carpets, Hamlyn Publishing, London (1966).