Preamble

For your convenience I have listed below posts in this series:

Arte Latino Textiles

Arte Latino Prints

Arte Latino Sculptures - Part I

Arte Latino Sculptures - Part II

Arte Latino Paintings - Part I

Arte Latino Paintings - Part II

Introduction

There are very few posts on this blogspot centering on sculptures and those that have are exhibited in museums. The three that come readily to mind are:

Louisiana Museum of Modern Art

Egyptian Museum Cairo - Part I

Egyptian Museum Cairo - Part II

Nevertheless, sculptures inform us about cultures and so play an important role in shaping our world view. Below is the first post on Arte Latino sculptures.

I hope you enjoy these sculptures as much as I do!

Marie-Therese

Arte Latino Sculptures - Part I[1]

Arte Latino explores the rich culture that runs through the American experience. The works below were created by artists from a vast array of backgrounds: Puerto Rican, Mexican, American, Cuban American, Central American and South American.

Artist and Title of Work: Patrocino Barela, Saint George (1935-43).

Technique and Materials: Juniper.

Size: 43.2 x 26.7 x 14.6 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Transer from the General Services Administration.

Comment[1]: The artist was born in Arizona but lived and labored in New Mexico, where he is credited with transforming traditional carving into a modern, personal idiom. Barela has been critically praised for his "crude, honest and personal expression." This sculpture is characteristic of Patrocino Barela's straightforward, expressive carvings on such themes as sprituality, morality, strength and struggle.

Artist and Title of Work: Maria Brito (1990).

Technique and Materials: Acrylic on wood and mixed media.

Size: 242.6 x 173.4 x 165.1 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Museum purchase through the Smithsonian Institution Collections Acquistion programme.

Comment[1]: A large, dark crack on the floor indicates a fissure of time and place - of memory. This is further amplified by the ominous shadow of tree branches on the crib. The reality of adulthood is represented by the kitchen, in which Brito has carefully arranged the utensils. The kitchen cabinet is partially open, allowing a glimpse of the elements of the artist's past. A fragile glass jar containing a small house sits on the sink counter in front of an old photograph. The artist was almost three years old when the snapshot was taken, likely at a birthday party. Of the three little girls at the bottom of the photograph, Brito is in the middle. She wears a striped party hat and a puzzled look. A small fragile twig sits in the water in the sink, with the hope that it will sprout. As a symbol of fertility, it might signify the regeneration of physical and cultural ties.

Artist and Title of Work: Carban Group, Los Reyes Magos (The Three Magi) (ca. 1875-1900).

Technique and Materials: Painted wood with metal and string.

Size: 20.7 x 30.3 x 15.3 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Teodoro Vidal Collection.

Comment[1]: Contrary to other cultures where Balthasar is the dark king, in Puerto Rico it is Melchior. In this figural grouping he is represented in the middle of the triad, flanked by the two white kings. According to local tradition, Melchoir is black because he has been burnt by rays of a star. The gifts they bear have allegorical significance - the gold, the incense and myrrh are symbols of Christ as king, god, and mortal. In anticipation of their arrival, puertorriqeno children leave boxes of hay and bowls of water under their beds for the king's horses.

These delightful figures were carved in the style of the Caban family. For several generations the Cabans worked in the town of Camuy, although works produced in their distinctive style are found throughout the island.

Artist and Title of Work: Charles M. Carrillo, Devocion de Nuevo Mexico (Devotion of New Mexico) (1998).

Technique and Materials: Gesso and natural pigments on pine.

Size: 2245.1 x 152.4 x 55.3 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Museum purchase made possible by William T. Evans and the Smithsonian Institution Collections Acquistion Program.

Comment[1]: In keeping with the nineteenth-century tradition, Carrillo made this pine altar using a mortise-and-tenon technique, without the use of nails or screws. The rich colors are hand-made from natural pigments derived from minerals, plants and natural clays. Although much smaller in scale, this reredos includes the same figures of saints as the main altar of the nineteenth century Catholic Church in the village of Las Trampas.

A prominent anthropologist, cultural historian, and teacher, Charles Carrillo has been called a "cultural warrior" for his zealous enthusiasm. He refers to the "belief system" as essential to the carver of religious figures. "If I truly didn't believe in it, I couldn't do it. If you don't believe you are just a painter of images."

Artist and Title of Work: Felipe de la Espada, San Benito Abad (Saint Benedict the Abbot) (ca. 1770-1818).

Technique and Materials: Painted cedar with glass.

Size: 87 x 41.3 x 34.9 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Teodoro Vidal Collection.

Comment[1]: In the old town of San German, located in the southwestern region of Puerto Rico, the production of santos, colorful wooden images of saints that are prayed to in time of public and private devotion, was an important business. This is where Felipe de la Espada and his family lived and worked. Of African ancestry, he was one of the most respected santeros in colonial times. In addition to his great skill as a carver, de la Espada was one of the very few in his community who could read - a notable accomplishment for a man of humble beginnings.

Artist and Title of Work: Rudy Fernandez, Escape (1987).

Technique and Materials: Painted wood, neon, lead and oil.

Size: 116.6 x 93.4 x 15.3 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: American Art Museum, gift of Fran K. Ribelin.

Comment[1]: In 1975, while teaching in Mexico City, Colorado-born Rudy Fernandez saw for the first time an exhibition of works by Frida Kahlo. Frustrated that his formal art education had excluded the arts of Mexico, Central and South America, he was determined to learn more about what he calls "pre-Cortesian" art. Since then he has developed a personal vocabulary of visual symbols, a unique vernacular that blends Chicano, Mexican and Anglo artistic and cultural references.

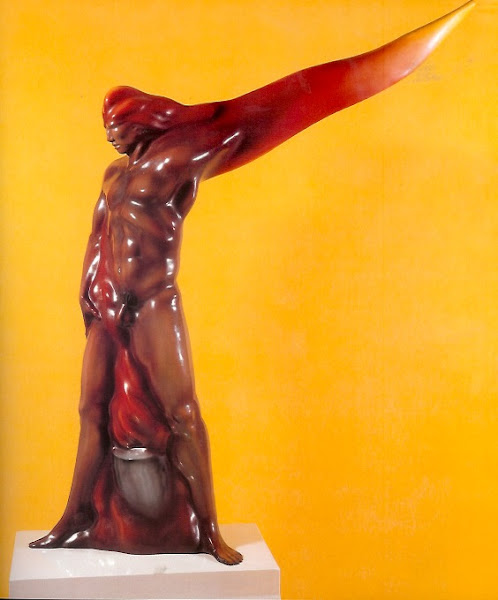

Artist and Title of Work: Luis Jimenez, Man on Fire (1969).

Technique and Materials: Fiberglass.

Size: 269.2 x 203.8 x 75 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: American Art Museum, gift of Philip Morris Incorporated.

Comment[1]: Luis Jimenez was born in El Paso into a family with a long history of craftsmanship. From his father, who had a business in neon "spectaculars", he established a strong foundation in welding, spray-painting, glassblowing and tinwork. During a three-month stay in Mexico, which represented for him a pilgrimage to his ancestral home, he turned to figurative art based on subjects from his heritage.

'Man on Fire' was created out of him viewing Vietnamese monks who set themselves on fire as a protest to the Vietnam war. The sculpture on a universal level, serves as a visual symbol of courageous action in the face of oppression.

Artist and Title of Work: Lares Group, La Virgen y el Nino (Virgin and Child) (ca. 1875 - 1900).

Technique and Materials: Fiberglass.

Size: 38.3 x 14 x 13.7 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: American Art Museum, Teodoro Vidal Collection.

Comment[1]: In La Virgen y el Nino (Virgin and Child), an elongated Madonna supports the Christ child on her forearm. Thick grooves in her black hair are echoed in the deep pleats of her flowing robe, which has been stippled with colorful dots. Suspended from her right hand is a milagro, an offering left in gratitude for divine intervention, perhaps from relief from medical ailment. Such Marian devotion continues to flourish in Puerto Rico today.

Artist and Title of Work: Felix Lopez, Nuestra Senora de los Dolores (Our Lady of Sorrows) (1998).

Technique and Materials: Gesso, natural pigments and dyes, pinon sap and gold leaf on pine and aspen.

Size: 212.1 x 59.7 x 59.7 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Museum purchase through the Smithsonian Institution Collections Acquistion Program.

Comment[1]: This elongated figure of the Virgin Mary, her halo radiant with gilding, grieves over the suffering and crucifixtion of her son, Jesus Christ. Traditionally, arrows or daggers pierce her heart as a symbol of great pain and sorrow, an image based on the Gospel verse: "Yea, a sword shall pierce through thine own soul also." Here, Lopez departs from tradition by eliminating the arrows from the saint's attributes. Additionally, he produced the elaborate niche in which "La Dolorosa" is standing. The harmonious result reflects the artist's deep spiritual and cultural roots.

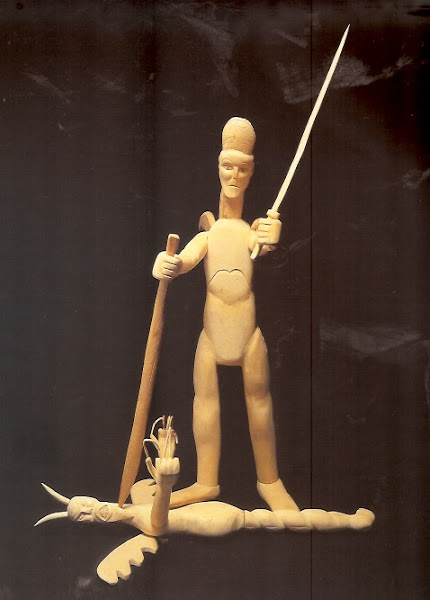

Artist and Title of Work: George Lopez, San Miguel el Arcangel y el Diablo (Saint Michael the Archangel and the Devil) (ca. 1955-56).

Technique and Materials: Aspen and mountain mahogany.

Size: 122 x 83.8 x 100.3 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Gift of Herbert Waide Hemphill Jr and museum purchase made possible by Ralph Cross Johnson.

Comment[1]: This animated sculpture was created by George Lopez, one of northern New Mexico's prominent santeros. The artist was taught by his father, Jose Dolores Lopez, who originated the Cordova style of chip-carved, unpainted statues. George Lopez used a saw, sharp knife, and sandpaper to create this simple yet powerful work, which reveals influences from Roman Catholicism, medieval Spanish art, as well as the Penitentes (a religious brotherhood of flagellants). In Cordova, New Mexico, nestled in the 7,000-foot-high valley of the Sangre de Cristo mountains, the artist learned about the lives of the saints in his religious household. He also learned about the devil, which he carved as a half-snake, half-insect-dragon.

Reference:

[1] J. Yorba, Arte Latino: Treasures from the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Watson-Guptill Publications, New York (2001).

For your convenience I have listed below posts in this series:

Arte Latino Textiles

Arte Latino Prints

Arte Latino Sculptures - Part I

Arte Latino Sculptures - Part II

Arte Latino Paintings - Part I

Arte Latino Paintings - Part II

Introduction

There are very few posts on this blogspot centering on sculptures and those that have are exhibited in museums. The three that come readily to mind are:

Louisiana Museum of Modern Art

Egyptian Museum Cairo - Part I

Egyptian Museum Cairo - Part II

Nevertheless, sculptures inform us about cultures and so play an important role in shaping our world view. Below is the first post on Arte Latino sculptures.

I hope you enjoy these sculptures as much as I do!

Marie-Therese

Arte Latino Sculptures - Part I[1]

Arte Latino explores the rich culture that runs through the American experience. The works below were created by artists from a vast array of backgrounds: Puerto Rican, Mexican, American, Cuban American, Central American and South American.

Artist and Title of Work: Patrocino Barela, Saint George (1935-43).

Technique and Materials: Juniper.

Size: 43.2 x 26.7 x 14.6 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Transer from the General Services Administration.

Comment[1]: The artist was born in Arizona but lived and labored in New Mexico, where he is credited with transforming traditional carving into a modern, personal idiom. Barela has been critically praised for his "crude, honest and personal expression." This sculpture is characteristic of Patrocino Barela's straightforward, expressive carvings on such themes as sprituality, morality, strength and struggle.

Artist and Title of Work: Maria Brito (1990).

Technique and Materials: Acrylic on wood and mixed media.

Size: 242.6 x 173.4 x 165.1 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Museum purchase through the Smithsonian Institution Collections Acquistion programme.

Comment[1]: A large, dark crack on the floor indicates a fissure of time and place - of memory. This is further amplified by the ominous shadow of tree branches on the crib. The reality of adulthood is represented by the kitchen, in which Brito has carefully arranged the utensils. The kitchen cabinet is partially open, allowing a glimpse of the elements of the artist's past. A fragile glass jar containing a small house sits on the sink counter in front of an old photograph. The artist was almost three years old when the snapshot was taken, likely at a birthday party. Of the three little girls at the bottom of the photograph, Brito is in the middle. She wears a striped party hat and a puzzled look. A small fragile twig sits in the water in the sink, with the hope that it will sprout. As a symbol of fertility, it might signify the regeneration of physical and cultural ties.

Artist and Title of Work: Carban Group, Los Reyes Magos (The Three Magi) (ca. 1875-1900).

Technique and Materials: Painted wood with metal and string.

Size: 20.7 x 30.3 x 15.3 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Teodoro Vidal Collection.

Comment[1]: Contrary to other cultures where Balthasar is the dark king, in Puerto Rico it is Melchior. In this figural grouping he is represented in the middle of the triad, flanked by the two white kings. According to local tradition, Melchoir is black because he has been burnt by rays of a star. The gifts they bear have allegorical significance - the gold, the incense and myrrh are symbols of Christ as king, god, and mortal. In anticipation of their arrival, puertorriqeno children leave boxes of hay and bowls of water under their beds for the king's horses.

These delightful figures were carved in the style of the Caban family. For several generations the Cabans worked in the town of Camuy, although works produced in their distinctive style are found throughout the island.

Artist and Title of Work: Charles M. Carrillo, Devocion de Nuevo Mexico (Devotion of New Mexico) (1998).

Technique and Materials: Gesso and natural pigments on pine.

Size: 2245.1 x 152.4 x 55.3 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Museum purchase made possible by William T. Evans and the Smithsonian Institution Collections Acquistion Program.

Comment[1]: In keeping with the nineteenth-century tradition, Carrillo made this pine altar using a mortise-and-tenon technique, without the use of nails or screws. The rich colors are hand-made from natural pigments derived from minerals, plants and natural clays. Although much smaller in scale, this reredos includes the same figures of saints as the main altar of the nineteenth century Catholic Church in the village of Las Trampas.

A prominent anthropologist, cultural historian, and teacher, Charles Carrillo has been called a "cultural warrior" for his zealous enthusiasm. He refers to the "belief system" as essential to the carver of religious figures. "If I truly didn't believe in it, I couldn't do it. If you don't believe you are just a painter of images."

Artist and Title of Work: Felipe de la Espada, San Benito Abad (Saint Benedict the Abbot) (ca. 1770-1818).

Technique and Materials: Painted cedar with glass.

Size: 87 x 41.3 x 34.9 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Teodoro Vidal Collection.

Comment[1]: In the old town of San German, located in the southwestern region of Puerto Rico, the production of santos, colorful wooden images of saints that are prayed to in time of public and private devotion, was an important business. This is where Felipe de la Espada and his family lived and worked. Of African ancestry, he was one of the most respected santeros in colonial times. In addition to his great skill as a carver, de la Espada was one of the very few in his community who could read - a notable accomplishment for a man of humble beginnings.

Artist and Title of Work: Rudy Fernandez, Escape (1987).

Technique and Materials: Painted wood, neon, lead and oil.

Size: 116.6 x 93.4 x 15.3 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: American Art Museum, gift of Fran K. Ribelin.

Comment[1]: In 1975, while teaching in Mexico City, Colorado-born Rudy Fernandez saw for the first time an exhibition of works by Frida Kahlo. Frustrated that his formal art education had excluded the arts of Mexico, Central and South America, he was determined to learn more about what he calls "pre-Cortesian" art. Since then he has developed a personal vocabulary of visual symbols, a unique vernacular that blends Chicano, Mexican and Anglo artistic and cultural references.

Artist and Title of Work: Luis Jimenez, Man on Fire (1969).

Technique and Materials: Fiberglass.

Size: 269.2 x 203.8 x 75 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: American Art Museum, gift of Philip Morris Incorporated.

Comment[1]: Luis Jimenez was born in El Paso into a family with a long history of craftsmanship. From his father, who had a business in neon "spectaculars", he established a strong foundation in welding, spray-painting, glassblowing and tinwork. During a three-month stay in Mexico, which represented for him a pilgrimage to his ancestral home, he turned to figurative art based on subjects from his heritage.

'Man on Fire' was created out of him viewing Vietnamese monks who set themselves on fire as a protest to the Vietnam war. The sculpture on a universal level, serves as a visual symbol of courageous action in the face of oppression.

Artist and Title of Work: Lares Group, La Virgen y el Nino (Virgin and Child) (ca. 1875 - 1900).

Technique and Materials: Fiberglass.

Size: 38.3 x 14 x 13.7 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: American Art Museum, Teodoro Vidal Collection.

Comment[1]: In La Virgen y el Nino (Virgin and Child), an elongated Madonna supports the Christ child on her forearm. Thick grooves in her black hair are echoed in the deep pleats of her flowing robe, which has been stippled with colorful dots. Suspended from her right hand is a milagro, an offering left in gratitude for divine intervention, perhaps from relief from medical ailment. Such Marian devotion continues to flourish in Puerto Rico today.

Artist and Title of Work: Felix Lopez, Nuestra Senora de los Dolores (Our Lady of Sorrows) (1998).

Technique and Materials: Gesso, natural pigments and dyes, pinon sap and gold leaf on pine and aspen.

Size: 212.1 x 59.7 x 59.7 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Museum purchase through the Smithsonian Institution Collections Acquistion Program.

Comment[1]: This elongated figure of the Virgin Mary, her halo radiant with gilding, grieves over the suffering and crucifixtion of her son, Jesus Christ. Traditionally, arrows or daggers pierce her heart as a symbol of great pain and sorrow, an image based on the Gospel verse: "Yea, a sword shall pierce through thine own soul also." Here, Lopez departs from tradition by eliminating the arrows from the saint's attributes. Additionally, he produced the elaborate niche in which "La Dolorosa" is standing. The harmonious result reflects the artist's deep spiritual and cultural roots.

Artist and Title of Work: George Lopez, San Miguel el Arcangel y el Diablo (Saint Michael the Archangel and the Devil) (ca. 1955-56).

Technique and Materials: Aspen and mountain mahogany.

Size: 122 x 83.8 x 100.3 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Gift of Herbert Waide Hemphill Jr and museum purchase made possible by Ralph Cross Johnson.

Comment[1]: This animated sculpture was created by George Lopez, one of northern New Mexico's prominent santeros. The artist was taught by his father, Jose Dolores Lopez, who originated the Cordova style of chip-carved, unpainted statues. George Lopez used a saw, sharp knife, and sandpaper to create this simple yet powerful work, which reveals influences from Roman Catholicism, medieval Spanish art, as well as the Penitentes (a religious brotherhood of flagellants). In Cordova, New Mexico, nestled in the 7,000-foot-high valley of the Sangre de Cristo mountains, the artist learned about the lives of the saints in his religious household. He also learned about the devil, which he carved as a half-snake, half-insect-dragon.

Reference:

[1] J. Yorba, Arte Latino: Treasures from the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Watson-Guptill Publications, New York (2001).