Preamble

For your convenience I have listed below posts in this series:

Arte Latino Textiles

Arte Latino Prints

Arte Latino Sculptures - Part I

Arte Latino Sculptures - Part II

Arte Latino Paintings - Part I

Arte Latino Paintings - Part II

Arte Latino Sculptures - Part II[1]

Artist and Title of Work: Gloria Lopez Cordova, Our Lady of Light (1997).

Technique and Materials: Aspen and juniper.

Size: 64.1 x 32.4 x 15.9 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Museum purchase through the Julia D. Strong Endowment.

Comment[1]: In Our Lady of Light, Lopez Cordova decorates the elborate crown with diamond shapes and motifs that represent the region's flowers. A decorated arc with nine lighted candles echoes the shape of the large crown, with its alternating triangles and finials carved from light-colored aspen and dark-colored juniper. Deeply incised chip carving and intricate patterns unify the work, including the sturdy circular base on which Our Lady of Light stands. The saint's hands and head are simply treated, her hair a ribbon-like pattern, and her face a combination of abstract shapes and forms.

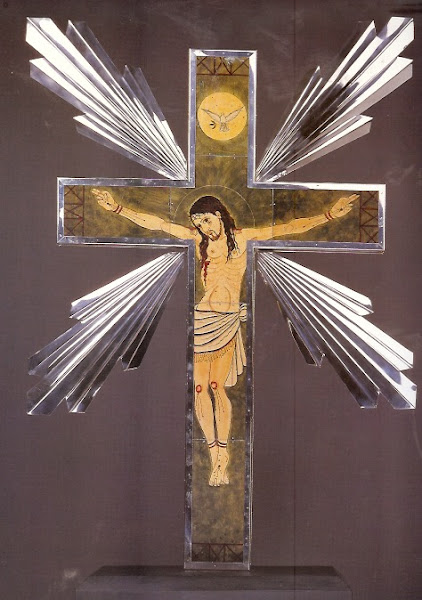

Artist and Title of Work:Ramon Jose Lopez, Liturgical Cross (1998).

Technique and Materials: Silver, mica and pigment on wood.

Size: 89.6 x 63.2 x 5 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Museum purchase made possible by William T. Evans.

Comment[1]: New Mexico artist Ramon Jose Lopez worked for a few years in construction before beginning his career as a jeweler and silversmith. The grandson of noted santero Lorenzo Lopez, he uses many of his grandfather's tools in his work. Ramon Lopez has said, "My traditional work [lets] me see how influenced I really was by my heritage, my history. It showed me my roots [and]...opened my eyes. I want to achieve the level...of those old masters...what they captured...emotions, so powerful, so moving." Lopez researches traditional methods and materials and masters them in his contemporary silver and gold jewelery, hollow ware, painted hides, reredos, escudos(reliquaries), and blacksmithing. In addition, he also produces ecclesiastical vessels, chalices with patens, pyxes, rosary boxes, furniture and architectural elements.

Artist and Title of Work: Emanuel Martínez, Farm Workers' Altar (1967).

Technique and Materials: Acrylic on mahogany and plywood.

Size: 96.9 x 138.5 x 91.4 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Gift of the International Bank of Commerce in honor of Antonio R. Sanchez Sr.

Comment[1]: Chicano artist Emanuel Martínez was about twenty when he created this altar to commemorate the workers' cause. Perfectly formed grape clusters evoke fruit that still today is boycotted by many Latinos as a symbol of conditions that inspired the farm workers' movement. On one side of the altar four hands of various shades grasp the vines - a symbol of unity, strength, and dignity in labor. Their secure grasp repeats the hands of the crucified brown-skinned Christ on an adjacent panel. A stylized black eagle flies proudly in front of an emblazoned red circle, the symbol of the United Farm Workers, the union that Cesar Chavez founded with Dolores Huerta and others. On the other side, a woman holds grapes in her left hand and corn in her right. Around her neck she wears a peace sign, in keeping with Chavez's practice of non violence. Overhead a large round sun contains a significant cultural icon: the mestizo tripartite head, a powerful symbol of the mixed heritage of many migrant workers.

Artist and Title of Work: Jesus Bautista Moroles, Georgia Stele (1999).

Technique and Materials: Granite.

Size: 208.3 x 31.1 x 520.3 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Gift of artist.

Comment[1]: In boyhood and young adult life, Jesus Bautista Moroles worked during summers with an uncle in Rockport, Texas, where he gained a strong foundation in stonemasonry. A series of courses taken at North Texas State University strengthened these skills. During 1980 the artist worked in a foundry at Pietrasanta, Italy, learning European sculpting techniques. On his return to Texas, Moroles started producing monumental granite sculpture for which he is well known today.

Artist and Title of Work: Jose Benito Ortega, Our Father Jesus of Nazareth (ca. 1885).

Technique and Materials: Painted wood and cloth with leather.

Size: 76.2 x 23.8 x 23.8 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Gift of Herbert Waide Hemphill Jr and museum purchase made possible by Ralph Cross Johnson.

Comment[1]: Ortega carved, Our Father Jesus of Nazareth, from boards discarded by lumber mills, which explains its flatness. The figure's small size and supporting wooden slats suggest that it was dressed and carried in Holy Week processions, probably by members of the Penitentes. These supporting slats - which help stablize the figure as it was carried - would normally be concealed under a garment when the figure was on display. Ortega's works are said to resemble people whom the artist used as models. This powerful image successfully conveys Christ's suffering through the downcast eyes, solemn face, exposed palms, and the graphic representation of bleeding. Ortega was among the early itinerant artist's working when mass-produced plaster statues began replacing traditional, hand-carved santos. Shortly after 1907, Ortega stopped carving.

Artist and Title of Work: Pepon Osorio, El Chandelier (1988).

Technique and Materials: Chandelier with found objects.

Size: 154.6 x 106.7 cm diam.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Museum purchased in part through the Smithsonian Institution Collections Acquistion Program.

Comment[1]: Walking through Spanish Harlem and the South Bronx, where he now lives, Osorio noticed that nearly every apartment had a chandelier. For the artist, these "floating crystal islands" were symbols of cultural pride in Puerto Rican neighborhoods. El Chandelier is fantastically - indeed excessively - decorated with swags of pearls and mass-produced miniature toys and objects, including palm trees, soccer balls, Afro-Caribbean saints, cars, dominoes, black and white babies, giraffes, and monkeys. The objects are metaphors for the immigrant popular culture of the 1950s and '60s, when islanders moved to the US mainland in significant numbers. At night the chandelier sparkles and, as a child once suggested, the multifaceted crystals recall the tears of the community.

Artist and Title of Work: Luis Tapia, Death Cart (1986).

Technique and Materials: Caspen with mica and human hair and teeth.

Size: 130.2 x 81 x 137.2 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Museum purchase made possible by Mrs Albert Bracket, John W. de Peyster, and Mrs Herbert Campbell.

Comment[1]: A native of Santa Fe, New Mexico, Luis Tapia is a self-taught contemporary artist. Like many of his generation, who grew up during a time of cultural homogenization - as well as the emergence of movements for civil rights and social consciousness- Tapia was determined to learn more about his culture. He began carving santos, studying them in churches and in collections at the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe. Around the same time, he helped found La Confradia de Artes y Artesanos Hispanicos, which has been instrumental in the contemporary revival of Southwest art.

Artist and Title of Work: Unidentified Artist, Christ Crucified (ca. 1820).

Technique and Materials: Painted wood with hair.

Size: 133 x 93.3 x 17.5 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Museum purchase through the Smithsonisn Institution Collections Acquisition Program.

Comment[1]: In this wooden sculpture, human hair falls limply over the Savior's scraggy shoulders, emphasizing the figure's lifelike presence. The gaunt, skeletal Christ grimaces not only in physical pain from asphyxia, but also in spirtual pain for humanity. His emaciated body and sunken chest combine to produce a powerful image. The ribs are formed by an abstract, chevron-like design that hovers over a protruding navel. Although blood oozes from wounds, the skin looks desiccated, much like the cross from which Christ hangs. Christ's attenuated limbs are countered by a strong, straight torso that tapers to thin, bony legs and nailed feet.

This significant work, remarkable for its pathos, is related to a long tradition of New Mexico carvings of saints' images. A smiliar crucifixion, perhaps carved by the same artist, is still venerated in a chapel in Cubero, New Mexico.

Artist and Title of Work: Unidentified Artist, Nuestra Senora de los Dolores (Our Lady of Sorrows) (ca. 1675 - 1725).

Technique and Materials: Painted wood.

Size: 37.8 x 18.4 x 14 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Teodoro Videl Collection.

Comment[1]: Carved in a highly dramatic style, this early Puerto Rican figure is reminiscent of 17th century Spanish baroque sculpture found in the island's Catholic Churches. The dynamic tension and energy of the Modonna's dark billowy robe symbolizes the grief of a tormented mother who has lost her beloved son. Deep pleats lead the viewer's eyes to her clenched hands. With her head mantled, her sorrowful eyes leads ours in the same upward gaze.

Artist and Title of Work: Horacio Valdez, Nuestra Senora La Reina del Cielo (Our Lady, Queen of Heaven) (1991).

Technique and Materials: Painted wood with metal and silver.

Size: 79.4 x 24.1 x 19.1 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Gift of Chuck and Jan Rosenak and museum purchase through Luisita L and Franz H Denghausen Endowment.

Comment[1]: This Virigin Mary wears a deep blue bodice with a bright red collar. A blend of colors, curves and contours, the figure is exquistively carved and painted, in acrylics rather than natural pigments. In a more traditional carving the Virgin Mary would be holding the Christ Child and a scepter. In Valdez's version, however, she wears a silver crown with a bright red accents and holds a palm frond in her left hand. The large stylized dove is a symbol of peace and the Holy Trinity. Her image, based on a passage in the Book of Revelations, La Reina del Cielo, or Our Queen of Heaven, offers protection from preternatural dangers.

Reference:

[1] J. Yorba, Arte Latino: Treasures from the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Watson-Guptill Publications, New York (2001).

For your convenience I have listed below posts in this series:

Arte Latino Textiles

Arte Latino Prints

Arte Latino Sculptures - Part I

Arte Latino Sculptures - Part II

Arte Latino Paintings - Part I

Arte Latino Paintings - Part II

Arte Latino Sculptures - Part II[1]

Artist and Title of Work: Gloria Lopez Cordova, Our Lady of Light (1997).

Technique and Materials: Aspen and juniper.

Size: 64.1 x 32.4 x 15.9 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Museum purchase through the Julia D. Strong Endowment.

Comment[1]: In Our Lady of Light, Lopez Cordova decorates the elborate crown with diamond shapes and motifs that represent the region's flowers. A decorated arc with nine lighted candles echoes the shape of the large crown, with its alternating triangles and finials carved from light-colored aspen and dark-colored juniper. Deeply incised chip carving and intricate patterns unify the work, including the sturdy circular base on which Our Lady of Light stands. The saint's hands and head are simply treated, her hair a ribbon-like pattern, and her face a combination of abstract shapes and forms.

Artist and Title of Work:Ramon Jose Lopez, Liturgical Cross (1998).

Technique and Materials: Silver, mica and pigment on wood.

Size: 89.6 x 63.2 x 5 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Museum purchase made possible by William T. Evans.

Comment[1]: New Mexico artist Ramon Jose Lopez worked for a few years in construction before beginning his career as a jeweler and silversmith. The grandson of noted santero Lorenzo Lopez, he uses many of his grandfather's tools in his work. Ramon Lopez has said, "My traditional work [lets] me see how influenced I really was by my heritage, my history. It showed me my roots [and]...opened my eyes. I want to achieve the level...of those old masters...what they captured...emotions, so powerful, so moving." Lopez researches traditional methods and materials and masters them in his contemporary silver and gold jewelery, hollow ware, painted hides, reredos, escudos(reliquaries), and blacksmithing. In addition, he also produces ecclesiastical vessels, chalices with patens, pyxes, rosary boxes, furniture and architectural elements.

Artist and Title of Work: Emanuel Martínez, Farm Workers' Altar (1967).

Technique and Materials: Acrylic on mahogany and plywood.

Size: 96.9 x 138.5 x 91.4 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Gift of the International Bank of Commerce in honor of Antonio R. Sanchez Sr.

Comment[1]: Chicano artist Emanuel Martínez was about twenty when he created this altar to commemorate the workers' cause. Perfectly formed grape clusters evoke fruit that still today is boycotted by many Latinos as a symbol of conditions that inspired the farm workers' movement. On one side of the altar four hands of various shades grasp the vines - a symbol of unity, strength, and dignity in labor. Their secure grasp repeats the hands of the crucified brown-skinned Christ on an adjacent panel. A stylized black eagle flies proudly in front of an emblazoned red circle, the symbol of the United Farm Workers, the union that Cesar Chavez founded with Dolores Huerta and others. On the other side, a woman holds grapes in her left hand and corn in her right. Around her neck she wears a peace sign, in keeping with Chavez's practice of non violence. Overhead a large round sun contains a significant cultural icon: the mestizo tripartite head, a powerful symbol of the mixed heritage of many migrant workers.

Artist and Title of Work: Jesus Bautista Moroles, Georgia Stele (1999).

Technique and Materials: Granite.

Size: 208.3 x 31.1 x 520.3 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Gift of artist.

Comment[1]: In boyhood and young adult life, Jesus Bautista Moroles worked during summers with an uncle in Rockport, Texas, where he gained a strong foundation in stonemasonry. A series of courses taken at North Texas State University strengthened these skills. During 1980 the artist worked in a foundry at Pietrasanta, Italy, learning European sculpting techniques. On his return to Texas, Moroles started producing monumental granite sculpture for which he is well known today.

Artist and Title of Work: Jose Benito Ortega, Our Father Jesus of Nazareth (ca. 1885).

Technique and Materials: Painted wood and cloth with leather.

Size: 76.2 x 23.8 x 23.8 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Gift of Herbert Waide Hemphill Jr and museum purchase made possible by Ralph Cross Johnson.

Comment[1]: Ortega carved, Our Father Jesus of Nazareth, from boards discarded by lumber mills, which explains its flatness. The figure's small size and supporting wooden slats suggest that it was dressed and carried in Holy Week processions, probably by members of the Penitentes. These supporting slats - which help stablize the figure as it was carried - would normally be concealed under a garment when the figure was on display. Ortega's works are said to resemble people whom the artist used as models. This powerful image successfully conveys Christ's suffering through the downcast eyes, solemn face, exposed palms, and the graphic representation of bleeding. Ortega was among the early itinerant artist's working when mass-produced plaster statues began replacing traditional, hand-carved santos. Shortly after 1907, Ortega stopped carving.

Artist and Title of Work: Pepon Osorio, El Chandelier (1988).

Technique and Materials: Chandelier with found objects.

Size: 154.6 x 106.7 cm diam.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Museum purchased in part through the Smithsonian Institution Collections Acquistion Program.

Comment[1]: Walking through Spanish Harlem and the South Bronx, where he now lives, Osorio noticed that nearly every apartment had a chandelier. For the artist, these "floating crystal islands" were symbols of cultural pride in Puerto Rican neighborhoods. El Chandelier is fantastically - indeed excessively - decorated with swags of pearls and mass-produced miniature toys and objects, including palm trees, soccer balls, Afro-Caribbean saints, cars, dominoes, black and white babies, giraffes, and monkeys. The objects are metaphors for the immigrant popular culture of the 1950s and '60s, when islanders moved to the US mainland in significant numbers. At night the chandelier sparkles and, as a child once suggested, the multifaceted crystals recall the tears of the community.

Artist and Title of Work: Luis Tapia, Death Cart (1986).

Technique and Materials: Caspen with mica and human hair and teeth.

Size: 130.2 x 81 x 137.2 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Museum purchase made possible by Mrs Albert Bracket, John W. de Peyster, and Mrs Herbert Campbell.

Comment[1]: A native of Santa Fe, New Mexico, Luis Tapia is a self-taught contemporary artist. Like many of his generation, who grew up during a time of cultural homogenization - as well as the emergence of movements for civil rights and social consciousness- Tapia was determined to learn more about his culture. He began carving santos, studying them in churches and in collections at the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe. Around the same time, he helped found La Confradia de Artes y Artesanos Hispanicos, which has been instrumental in the contemporary revival of Southwest art.

Artist and Title of Work: Unidentified Artist, Christ Crucified (ca. 1820).

Technique and Materials: Painted wood with hair.

Size: 133 x 93.3 x 17.5 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Museum purchase through the Smithsonisn Institution Collections Acquisition Program.

Comment[1]: In this wooden sculpture, human hair falls limply over the Savior's scraggy shoulders, emphasizing the figure's lifelike presence. The gaunt, skeletal Christ grimaces not only in physical pain from asphyxia, but also in spirtual pain for humanity. His emaciated body and sunken chest combine to produce a powerful image. The ribs are formed by an abstract, chevron-like design that hovers over a protruding navel. Although blood oozes from wounds, the skin looks desiccated, much like the cross from which Christ hangs. Christ's attenuated limbs are countered by a strong, straight torso that tapers to thin, bony legs and nailed feet.

This significant work, remarkable for its pathos, is related to a long tradition of New Mexico carvings of saints' images. A smiliar crucifixion, perhaps carved by the same artist, is still venerated in a chapel in Cubero, New Mexico.

Artist and Title of Work: Unidentified Artist, Nuestra Senora de los Dolores (Our Lady of Sorrows) (ca. 1675 - 1725).

Technique and Materials: Painted wood.

Size: 37.8 x 18.4 x 14 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Teodoro Videl Collection.

Comment[1]: Carved in a highly dramatic style, this early Puerto Rican figure is reminiscent of 17th century Spanish baroque sculpture found in the island's Catholic Churches. The dynamic tension and energy of the Modonna's dark billowy robe symbolizes the grief of a tormented mother who has lost her beloved son. Deep pleats lead the viewer's eyes to her clenched hands. With her head mantled, her sorrowful eyes leads ours in the same upward gaze.

Artist and Title of Work: Horacio Valdez, Nuestra Senora La Reina del Cielo (Our Lady, Queen of Heaven) (1991).

Technique and Materials: Painted wood with metal and silver.

Size: 79.4 x 24.1 x 19.1 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Gift of Chuck and Jan Rosenak and museum purchase through Luisita L and Franz H Denghausen Endowment.

Comment[1]: This Virigin Mary wears a deep blue bodice with a bright red collar. A blend of colors, curves and contours, the figure is exquistively carved and painted, in acrylics rather than natural pigments. In a more traditional carving the Virgin Mary would be holding the Christ Child and a scepter. In Valdez's version, however, she wears a silver crown with a bright red accents and holds a palm frond in her left hand. The large stylized dove is a symbol of peace and the Holy Trinity. Her image, based on a passage in the Book of Revelations, La Reina del Cielo, or Our Queen of Heaven, offers protection from preternatural dangers.

Reference:

[1] J. Yorba, Arte Latino: Treasures from the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Watson-Guptill Publications, New York (2001).