Preamble

For your convenience I have listed below all posts in this series:

Arte Latino Textiles

Arte Latino Prints

Arte Latino Sculptures - Part I

Arte Latino Sculptures - Part II

Arte Latino Paintings - Part I

Arte Latino Paintings - Part II

Latino Artworks

Introduction

In America, like Australia, indigenous cultures were over run initially by a wave of British immigrants. This was heightened after World War Two because of Australia's near death experience of a Japanese invasion and so the mantra was 'Populate or Perish' and so a wave of so called 'Ten Pound Poms' immigrated to Australia to escape the 'after war' poverty of Great Britain.

The American indigenous population was swamped by wave after wave of immigrants. First the British and then later by South American immigrants seeking a better life. As a result, more recent American art owes a profound debt to the Latino population, even though Hispanics were among the earliest settlers of this continent, and their influence was proportionately strong, especially in such states as California and New Mexico. This can be especially seen in American museums, where the earliest works in the collection was made by Puerto Rican artists and some of the most contemporary images reflect diverse Latino cultures. No such artistic trail of non British immigration occurred in the collections of Australian Art Institutions and/or Museums, mainly because such institutions to this day are beholden to the British.

Latino Artworks [1]

Artist: Pedro Antonio Fresquîs (1749-1831).

Title: Our Lady of Guadalupe.

Technique and Materials: Painted Wood.

Size: 47.3 x 27.3 x 2.2 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Gift of Herbert Waide Hemphill Jr. and museum purchase made possible by Ralph Cross Johnson.

Comment[1]: In 1531, the Virgin Mary miraculously appeared before a Native American shepherd who had recently converted to Catholicism. She told him to ask the Bishop to erect a church in her honor on the hill of Tepeyac, an ancient Aztec holy site dedicated to the mother goddess Tonantzin. As proof of the Virgin's appearance, she instructed the shepherd to fill his cape with roses from this hill where cacti usually grew. When he emptied the fragrant contents before the Bishop, the onlookers saw the image of a brown-skinned Virgin imprinted on the cloth. The mixing of the former indigenous Aztec Goddess and the Catholic Saint gave birth to a new cult of the Virgin of Guadalupe.

This delicately painted retablo (devotional panel) is attribued to the early New Mexican santero Pedro Antonio Fresquîs. The Virgin stands atop of a dark crescent-shaped moon, surrounded by glowing light called, mandorla. Outside this celestial realm the artist embellished the border with his trademark decorative flowers and vine-like designs.

Artist: Ana Mendieta (1948-1985).

Title: Untitled from the 'Silueta' series.

Technique and Materials: Photograph (1980).

Size: 98.4 x 133.4 cm.

Acquisition: Smithsonian American Art Museum. Museum purchase in oart through the Smithsonian Institution Collection Acquisition Program.

Comment[1]: Ana Mendieta was a sculpture, and performance and conceptual artist. She was born in Havana, Cuba, and came to the United States in 1961, when many Cubans were fleeing Fidel Casrtro's regime. Mendieta and her sisters were raised in different orphanages and foster homes in Iowa. Although she eventually studied at the Center for the New Performing Arts at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, she always considered herself an artist in exile.

Mendieta often used her body as a template for silhouettes shaped in mud. Carving directly into the clay bed, she re-established connections with her ancestors and ancestral land. This female contour inscribed in the earth recalls earth goddesses of ancient cultures, reflecting Mendieta's feminist stance. The art of carving provided Mendieta with links to the timeless universe. As she remarked poetically, 'I have thrown myself into the very elements that produced me, using the earth as my canvas and my soul as my tools.' She made this photograph as a record of her ephemeral sculpture.

Artist: Abelardo Morell (1948 - ).

Title: Camera Obscura Image of Manhattan: View Looking West in Empty Room.

Technique and Materials: Silver Paint (1996).

Size: 74.9 x 100.3 cm.

Acquisition: Smithsonian American Art Museum. Gift of the Consolidated Natural Gas Company Foundation.

Comment[1]: Abelardo Morell was born in Havana. As a child he felt a sense of alienation and isolation in Cuba, feelings that remained when he moved as a teenager with his family to New York City. Although he later studied comparative religion at Bowdoin College, he eventually took up photography as a way to express his feelings as an immigrant to the United States during the turbulent 1960s.

In this curious photograph the New York skyline is turned upside down. As the dense cityscape fills the room - empty save for the ladder and the electric cord - the effect is disorienting yet poetic. To achieve this effect, Morell used an old imaging process in a new way: he literally turned the entire room into a camera. Use of the camera obscura - literally 'dark room' - dates to the seventeenth century, well before the advent of conventional photography. Morell covered the windows in the empty room with black plastic, into which he cut a small hole to serve as the camera's aperture. As light entered from the outside, it projected onto the opposite wall an inverted image of Manhattan. On the wall near the aperture the photographer placed a large-format camera on a tripod - in effect, placing a camera within a camera. After an exposure of about eight hours this image was produced. The result is an eerie juxtaposition of an interior/exterior, an ambiguous new image that serves as a metaphor for private and public life.

Artist: Joseph Rodrîguez (1951 - ).

Title: Mothers on the Steps.

Technique and Materials: Chromogenic photograph (1988).

Size: 45.7 x 30.5 cm.

Acquisition: Smithsonian American Art Museum. Gift of the artist.

Comment[1]: Joseph Rodrîguez was shy as a child, so discovering photography was a revelation, becoming a way for him to communicate. To get close to his subjects, he spends a lot of time with them. 'The only way to get a really good photograph is by listening to people,' says Rodrîguez who believes that listening is often more important than taking the photograph. As he further stated, 'I feel very rich when I see pictures with emotion in them that I've created. That's my big pay back. It's very personal.'

In this lush chromogenic photograph, Rodrîguez captured a moment in the lives of four Puerto Rican mothers and their children. This image is part of a large documentary project, in which Rodrîguez took seven hundred rolls of film during four years to capture the story of Spanish Harlem, a traditional Puerto Rican neigborhood in New York. The series captured what the artist refers to as 'the drama of a rich community.'

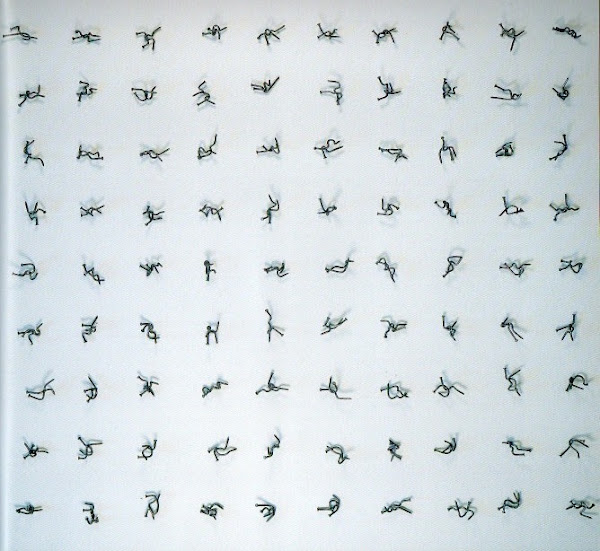

Artist: Ruben Trejo (1937 - ).

Title: Codex for the 21st Century.

Technique and Materials: Nails (1997).

Size: 152.4 x 609.6 cm.

Acquisition: Smithsonian American Art Museum. Museum purchase through the Julia D. Strong Endowment and Acquisition Fund.

Comment[1]: Against a stark background, one hundred pairs of nails twist around one another, suggesting images of chromosomes, dancers - even, as Trejo points out, the Kama Sutra. The nails, which were specifically bent and rusted by the artist, can be reconfigured. The resulting images resemble abstract characters on a futuristic three-dimensional codex.

Ruben Trejo was born in a boxcar in the Burlington Railroad Yard in Saint Paul, Minnesota. His father worked for the railroad and his mother and siblings worked the fields as migrant laborers. Trejo recognized that Chicano artists were experiencing 'cultural doldrums,' and as a way to 'drive some life into our visual culture,' he looked to ancient Aztec and Mayan codices for inspiration. At The Mexican Museum in 1992, Trejo was among several artists commissioned to make collective works that symbolically gathered the lost picture books of the Americas, burned by the colonial administration during the Spanish conquest. This Codex for the 21st Century represents another step in that direction, although Trejo communicates in a language that the viewer can only attempt to understand. This deceptively simple work allows the viewer to assume the role of an archaeologist discovering new, not-yet-deciphered language, while engaging in a dialogue about art and culture. As a poet he wrote many years ago: 'I sing the pictures of the book and see them spread out; I am an elegant bird for I make the codices speak within the house of pictures.'

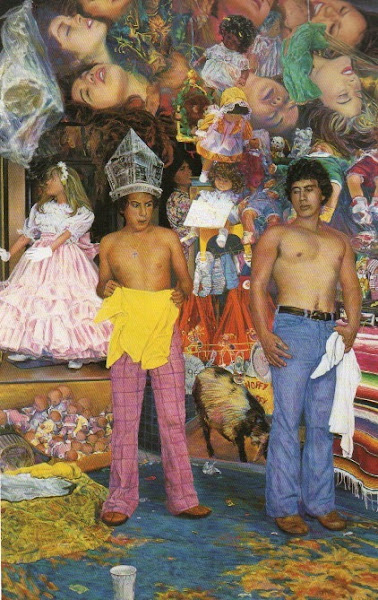

Artist: John Valadez (1951 - ).

Title: Two Vendors (1989).

Technique and Materials: Pastel.

Size: 208.9 x 128.3 cm.

Acquisition: Smithsonian American Art Museum. Museum purchase through the Smithsonian Institution Collections Acquisition Program and the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment.

Comment[1]: On a hot summer day in downtown Los Angeles, John Valadez was looking for interesting subjects to photograph along Broadway Street. He became transfixed as he watched two men pass one another, each giving the other a look that forcefully proclaimed their right alone to be shirtless. Holding his bright yellow shirt and wearing a chain with a cross and a newspaper hat suggestive of a miter, the young man on the left had a quizzical expression. The other man, also shirtless, adds to the sense of competition. Above them a number of female heads float amidst dolls and the Virgin. Valadez, a superb draftsman and brilliant colorist, captured this moment in stunning pastel. The dreamlike scene evokes sources such as Spanish language television and foto-novellas. The pastel's overall color scheme mimics the broad multi-hued bands of the serape.

As a youth in Los Angeles, Valadez played between the freeway and the river. While attending East Los Angeles Junior College he joins a theatre group that presented plays in prisons and community centers. In the late 1970s, he, along with Carlos Almaraz, Frank Romero and Richard Duareto, funded the Public Arts Center in Highland Park, which provided studio space and access to cooperative mural projects.

Artist: Martina Lopez (1952 - ).

Title: Heirs Come to Pass, 3 (1991).

Technique and Materials: Silver-dye bleach print made from digitally assisted montage.

Size: 76.2 x 127 cm.

Acquisition: Smithsonian American Art Museum. Gift of the Consolidated Natural Gas Company Foundation.

Comment[1]: Martina lopez uses old family photographs to create a collective history that not only allows her to express feelings of loss, but also provides a visual terrain in which viewers are able to insert their own ancestral memories. In 'Heirs Come to Pass, 3,' Victorian formailty meets desolation and ambuguity in a surreal dream world.

Reference:

[1] J. Yorba, Arte Latino: Treasures from the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Watson-Guptill Publications, New York (2001).

For your convenience I have listed below all posts in this series:

Arte Latino Textiles

Arte Latino Prints

Arte Latino Sculptures - Part I

Arte Latino Sculptures - Part II

Arte Latino Paintings - Part I

Arte Latino Paintings - Part II

Latino Artworks

Introduction

In America, like Australia, indigenous cultures were over run initially by a wave of British immigrants. This was heightened after World War Two because of Australia's near death experience of a Japanese invasion and so the mantra was 'Populate or Perish' and so a wave of so called 'Ten Pound Poms' immigrated to Australia to escape the 'after war' poverty of Great Britain.

The American indigenous population was swamped by wave after wave of immigrants. First the British and then later by South American immigrants seeking a better life. As a result, more recent American art owes a profound debt to the Latino population, even though Hispanics were among the earliest settlers of this continent, and their influence was proportionately strong, especially in such states as California and New Mexico. This can be especially seen in American museums, where the earliest works in the collection was made by Puerto Rican artists and some of the most contemporary images reflect diverse Latino cultures. No such artistic trail of non British immigration occurred in the collections of Australian Art Institutions and/or Museums, mainly because such institutions to this day are beholden to the British.

Latino Artworks [1]

Artist: Pedro Antonio Fresquîs (1749-1831).

Title: Our Lady of Guadalupe.

Technique and Materials: Painted Wood.

Size: 47.3 x 27.3 x 2.2 cm.

Courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Acquisition: Gift of Herbert Waide Hemphill Jr. and museum purchase made possible by Ralph Cross Johnson.

Comment[1]: In 1531, the Virgin Mary miraculously appeared before a Native American shepherd who had recently converted to Catholicism. She told him to ask the Bishop to erect a church in her honor on the hill of Tepeyac, an ancient Aztec holy site dedicated to the mother goddess Tonantzin. As proof of the Virgin's appearance, she instructed the shepherd to fill his cape with roses from this hill where cacti usually grew. When he emptied the fragrant contents before the Bishop, the onlookers saw the image of a brown-skinned Virgin imprinted on the cloth. The mixing of the former indigenous Aztec Goddess and the Catholic Saint gave birth to a new cult of the Virgin of Guadalupe.

This delicately painted retablo (devotional panel) is attribued to the early New Mexican santero Pedro Antonio Fresquîs. The Virgin stands atop of a dark crescent-shaped moon, surrounded by glowing light called, mandorla. Outside this celestial realm the artist embellished the border with his trademark decorative flowers and vine-like designs.

Artist: Ana Mendieta (1948-1985).

Title: Untitled from the 'Silueta' series.

Technique and Materials: Photograph (1980).

Size: 98.4 x 133.4 cm.

Acquisition: Smithsonian American Art Museum. Museum purchase in oart through the Smithsonian Institution Collection Acquisition Program.

Comment[1]: Ana Mendieta was a sculpture, and performance and conceptual artist. She was born in Havana, Cuba, and came to the United States in 1961, when many Cubans were fleeing Fidel Casrtro's regime. Mendieta and her sisters were raised in different orphanages and foster homes in Iowa. Although she eventually studied at the Center for the New Performing Arts at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, she always considered herself an artist in exile.

Mendieta often used her body as a template for silhouettes shaped in mud. Carving directly into the clay bed, she re-established connections with her ancestors and ancestral land. This female contour inscribed in the earth recalls earth goddesses of ancient cultures, reflecting Mendieta's feminist stance. The art of carving provided Mendieta with links to the timeless universe. As she remarked poetically, 'I have thrown myself into the very elements that produced me, using the earth as my canvas and my soul as my tools.' She made this photograph as a record of her ephemeral sculpture.

Artist: Abelardo Morell (1948 - ).

Title: Camera Obscura Image of Manhattan: View Looking West in Empty Room.

Technique and Materials: Silver Paint (1996).

Size: 74.9 x 100.3 cm.

Acquisition: Smithsonian American Art Museum. Gift of the Consolidated Natural Gas Company Foundation.

Comment[1]: Abelardo Morell was born in Havana. As a child he felt a sense of alienation and isolation in Cuba, feelings that remained when he moved as a teenager with his family to New York City. Although he later studied comparative religion at Bowdoin College, he eventually took up photography as a way to express his feelings as an immigrant to the United States during the turbulent 1960s.

In this curious photograph the New York skyline is turned upside down. As the dense cityscape fills the room - empty save for the ladder and the electric cord - the effect is disorienting yet poetic. To achieve this effect, Morell used an old imaging process in a new way: he literally turned the entire room into a camera. Use of the camera obscura - literally 'dark room' - dates to the seventeenth century, well before the advent of conventional photography. Morell covered the windows in the empty room with black plastic, into which he cut a small hole to serve as the camera's aperture. As light entered from the outside, it projected onto the opposite wall an inverted image of Manhattan. On the wall near the aperture the photographer placed a large-format camera on a tripod - in effect, placing a camera within a camera. After an exposure of about eight hours this image was produced. The result is an eerie juxtaposition of an interior/exterior, an ambiguous new image that serves as a metaphor for private and public life.

Artist: Joseph Rodrîguez (1951 - ).

Title: Mothers on the Steps.

Technique and Materials: Chromogenic photograph (1988).

Size: 45.7 x 30.5 cm.

Acquisition: Smithsonian American Art Museum. Gift of the artist.

Comment[1]: Joseph Rodrîguez was shy as a child, so discovering photography was a revelation, becoming a way for him to communicate. To get close to his subjects, he spends a lot of time with them. 'The only way to get a really good photograph is by listening to people,' says Rodrîguez who believes that listening is often more important than taking the photograph. As he further stated, 'I feel very rich when I see pictures with emotion in them that I've created. That's my big pay back. It's very personal.'

In this lush chromogenic photograph, Rodrîguez captured a moment in the lives of four Puerto Rican mothers and their children. This image is part of a large documentary project, in which Rodrîguez took seven hundred rolls of film during four years to capture the story of Spanish Harlem, a traditional Puerto Rican neigborhood in New York. The series captured what the artist refers to as 'the drama of a rich community.'

Artist: Ruben Trejo (1937 - ).

Title: Codex for the 21st Century.

Technique and Materials: Nails (1997).

Size: 152.4 x 609.6 cm.

Acquisition: Smithsonian American Art Museum. Museum purchase through the Julia D. Strong Endowment and Acquisition Fund.

Comment[1]: Against a stark background, one hundred pairs of nails twist around one another, suggesting images of chromosomes, dancers - even, as Trejo points out, the Kama Sutra. The nails, which were specifically bent and rusted by the artist, can be reconfigured. The resulting images resemble abstract characters on a futuristic three-dimensional codex.

Ruben Trejo was born in a boxcar in the Burlington Railroad Yard in Saint Paul, Minnesota. His father worked for the railroad and his mother and siblings worked the fields as migrant laborers. Trejo recognized that Chicano artists were experiencing 'cultural doldrums,' and as a way to 'drive some life into our visual culture,' he looked to ancient Aztec and Mayan codices for inspiration. At The Mexican Museum in 1992, Trejo was among several artists commissioned to make collective works that symbolically gathered the lost picture books of the Americas, burned by the colonial administration during the Spanish conquest. This Codex for the 21st Century represents another step in that direction, although Trejo communicates in a language that the viewer can only attempt to understand. This deceptively simple work allows the viewer to assume the role of an archaeologist discovering new, not-yet-deciphered language, while engaging in a dialogue about art and culture. As a poet he wrote many years ago: 'I sing the pictures of the book and see them spread out; I am an elegant bird for I make the codices speak within the house of pictures.'

Artist: John Valadez (1951 - ).

Title: Two Vendors (1989).

Technique and Materials: Pastel.

Size: 208.9 x 128.3 cm.

Acquisition: Smithsonian American Art Museum. Museum purchase through the Smithsonian Institution Collections Acquisition Program and the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment.

Comment[1]: On a hot summer day in downtown Los Angeles, John Valadez was looking for interesting subjects to photograph along Broadway Street. He became transfixed as he watched two men pass one another, each giving the other a look that forcefully proclaimed their right alone to be shirtless. Holding his bright yellow shirt and wearing a chain with a cross and a newspaper hat suggestive of a miter, the young man on the left had a quizzical expression. The other man, also shirtless, adds to the sense of competition. Above them a number of female heads float amidst dolls and the Virgin. Valadez, a superb draftsman and brilliant colorist, captured this moment in stunning pastel. The dreamlike scene evokes sources such as Spanish language television and foto-novellas. The pastel's overall color scheme mimics the broad multi-hued bands of the serape.

As a youth in Los Angeles, Valadez played between the freeway and the river. While attending East Los Angeles Junior College he joins a theatre group that presented plays in prisons and community centers. In the late 1970s, he, along with Carlos Almaraz, Frank Romero and Richard Duareto, funded the Public Arts Center in Highland Park, which provided studio space and access to cooperative mural projects.

Artist: Martina Lopez (1952 - ).

Title: Heirs Come to Pass, 3 (1991).

Technique and Materials: Silver-dye bleach print made from digitally assisted montage.

Size: 76.2 x 127 cm.

Acquisition: Smithsonian American Art Museum. Gift of the Consolidated Natural Gas Company Foundation.

Comment[1]: Martina lopez uses old family photographs to create a collective history that not only allows her to express feelings of loss, but also provides a visual terrain in which viewers are able to insert their own ancestral memories. In 'Heirs Come to Pass, 3,' Victorian formailty meets desolation and ambuguity in a surreal dream world.

Reference:

[1] J. Yorba, Arte Latino: Treasures from the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Watson-Guptill Publications, New York (2001).