Preamble:

One of my favourite pastimes is to grab a white piece of cloth (be it silk, a pashmina etc.) and create my own colored scarf or shawl. It amazes me how many people who buy my wearable art do so because they know it's an artwork that on wearing, they will never see a similar wearable art piece walking towards them. Click on the following link to get an glimpse of what I do - My New Hand Dyed and Hand Printed 'Rainforest Beauty' Pashmina Wraps Collection. This website will lead you to other links that highlight the range of my wearable art.

If you like any of my artworks in the above links, please email me at - Marie-Therese - for pricing and for any queries you might have.

The Shawl

A Fashion Garment of the 19th Century [1]

The shawl arrived relatively late as a garment in Western fashion. Like so many other wearables, the West borrowed it from Asia.

Technically the shawl is a garment. The word 'shawl' derives from 14th Century Persia. They were woven rectangles worn over the shoulders and made from the fur of Kashmiri goats. Kashmir at that time in history was a major trade center.

The first shawls in Europe were brought to England by the East India Company in the mid-eighteenth century.

Captain John Foote of the Honorable East India Company, painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1761. The outfit depicted in the portrait now appears in the collection of the York Museums, UK.

When the Empire style developed soon after, modelled on classic Greek and Roman dress styles, the wrapping shawl became a fashion garment together with close fitting dresses without stiff frames. Not only did the shawl fit in well with the soft style with many folds, it was also a necessity to give both cover and heat in view of the very thin dress material which was dictated by fashion at that time.

Fashion plate with a European 'geniune shawl' from the Journal - des damas et des demoiselles (March, 1857).

The shawl that was brought to Europe was a male garment from Kashmir, a province of northern India. It was a high-status garment of prime wool quality which had been used in its homeland as a precious gift between princes and other well-off people. In Europe, these luxury garments, with their slow method of manufacture, were of course highly expensive and so only available to the wealthiest.

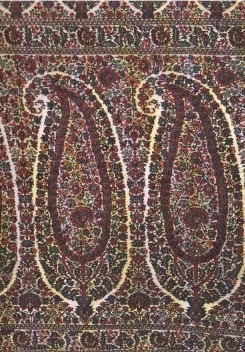

Genuine shawl from Kashmir.

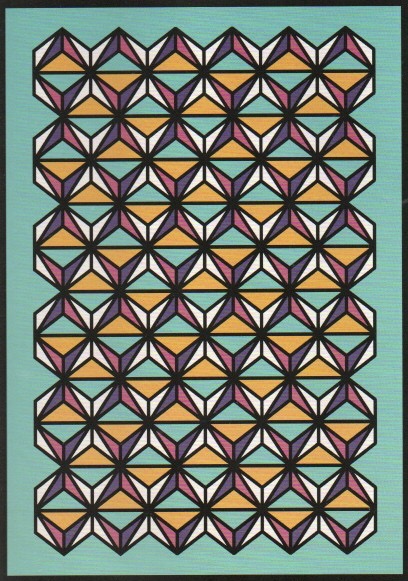

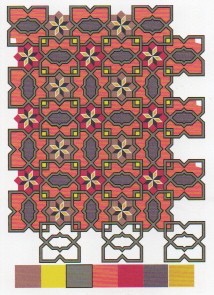

A European copy of a Kashmiri shawl.

The fashion was so attractive, and the desire to own such a sensual garment was so overwhelming, that the skilled weavers, above all in England and Scotland, by 1780 had devised a simpler method for imitating the genuine Kashmir shawls. That was how they became to be called 'genuine shawls' in such countries as Sweden. Fashion cities like Paris and Vienna began their own manufacture just after the 1800s. At the same time, shawl weaving was also started in Paisley in Scotland. This soon became the most famous place yielding the greatest production of this garment. The pattern that was associated with genuine shawls, is still called to this day, Paisley pattern when it appears at regular intervals as a new fashion pattern. The pattern, which is also known in Sweden as 'shawl gherkins' and in America as 'Persian pickles', or by the Hindi word 'mir-i-bota' or 'buta', was increasingly stylized and eventually ended up covering the entire shawl.

A woman wearing a Paisley shawl.

Photograph courtesy of Nordska Museet.

A garment that was subject to fashion as the shawl was, of course, required constant renewal and adaptation to changing fads. By the mid nineteenth century shawls had also spread to people in the lower strata of sociey, becoming a favourite outer garment, since they were easy to wrap around and affordable because no tailoring was required. When the shawl disappeared as a fashion garment, which happened when the bustle replaced the crinoline in the 1870s, it lived on as the most common female folk garment at least until 1900, and in places in Britain even later.

Paisley shawl from the beginning of the twentieth century.

Nanna Snygg from Fleminge.

Courtesy of Nordiska Museet.

Home-woven checked woollen shawls could be found on most farmer's wives and could be used for many purposes, not just as a woman's outer garment. With a shawl, one could always keep warm, so it was suitable for old people shivering in their bedrooms, for swaddling infants on the way to church, or wrapped round a school child with several kilometers to walk to school on an icy morning with snow swirling.

The European copies were strikingly often worn as bridal shawls. This shows how much of an exclusive ceremonial garment the shawl had become. Woven shawls were in turn copied and printed on fabrics, in descending quality from silk to cotton and wool, with patterns that repeated the miribota motif closely or more imaginatively. Yet no matter what the quality, shawls were the best garments for those who could afford them. When shawls went out of fashion in the 1870s, in particular the Paisley shawls, they were not thrown away - they were too good for that! Rather, they were given new functions. They were big enough to serve as door drapes, tablecloths, and piano covers, or they could be converted into a full-length dressing gown or evening coat.

Throughout the twentieth century, from time to time, the shawl made a comeback in fashion. The Paisley pattern remained popular and familiar. For example, most people have owned at least one handkerchief with this pattern. Pashmina shawls remain in demand. Today it is not just teenagers, who wrap a large shawl around their neck during the coldest days.

My new, contemporary ArtCloth pashmina wraps collection, named, “Urban Codes - Series 1”, is based on the current Western revival of tattoos and tattoo body art. It is a limited-edition series which will not be repeated. Click on the following link to view all of my unique scarves - My New Hand Dyed and Hand Printed ‘Urban Codes - Series 1’ Pashmina Wraps Collection.

Reference:

[1] The Power of Fashion: 300 Years of Clothing, Berit Eldvik, Catalog for the exhibition - Power of Fashion, Halmstad (2010).

One of my favourite pastimes is to grab a white piece of cloth (be it silk, a pashmina etc.) and create my own colored scarf or shawl. It amazes me how many people who buy my wearable art do so because they know it's an artwork that on wearing, they will never see a similar wearable art piece walking towards them. Click on the following link to get an glimpse of what I do - My New Hand Dyed and Hand Printed 'Rainforest Beauty' Pashmina Wraps Collection. This website will lead you to other links that highlight the range of my wearable art.

If you like any of my artworks in the above links, please email me at - Marie-Therese - for pricing and for any queries you might have.

The Shawl

A Fashion Garment of the 19th Century [1]

The shawl arrived relatively late as a garment in Western fashion. Like so many other wearables, the West borrowed it from Asia.

Technically the shawl is a garment. The word 'shawl' derives from 14th Century Persia. They were woven rectangles worn over the shoulders and made from the fur of Kashmiri goats. Kashmir at that time in history was a major trade center.

The first shawls in Europe were brought to England by the East India Company in the mid-eighteenth century.

Captain John Foote of the Honorable East India Company, painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1761. The outfit depicted in the portrait now appears in the collection of the York Museums, UK.

When the Empire style developed soon after, modelled on classic Greek and Roman dress styles, the wrapping shawl became a fashion garment together with close fitting dresses without stiff frames. Not only did the shawl fit in well with the soft style with many folds, it was also a necessity to give both cover and heat in view of the very thin dress material which was dictated by fashion at that time.

Fashion plate with a European 'geniune shawl' from the Journal - des damas et des demoiselles (March, 1857).

The shawl that was brought to Europe was a male garment from Kashmir, a province of northern India. It was a high-status garment of prime wool quality which had been used in its homeland as a precious gift between princes and other well-off people. In Europe, these luxury garments, with their slow method of manufacture, were of course highly expensive and so only available to the wealthiest.

Genuine shawl from Kashmir.

A European copy of a Kashmiri shawl.

The fashion was so attractive, and the desire to own such a sensual garment was so overwhelming, that the skilled weavers, above all in England and Scotland, by 1780 had devised a simpler method for imitating the genuine Kashmir shawls. That was how they became to be called 'genuine shawls' in such countries as Sweden. Fashion cities like Paris and Vienna began their own manufacture just after the 1800s. At the same time, shawl weaving was also started in Paisley in Scotland. This soon became the most famous place yielding the greatest production of this garment. The pattern that was associated with genuine shawls, is still called to this day, Paisley pattern when it appears at regular intervals as a new fashion pattern. The pattern, which is also known in Sweden as 'shawl gherkins' and in America as 'Persian pickles', or by the Hindi word 'mir-i-bota' or 'buta', was increasingly stylized and eventually ended up covering the entire shawl.

A woman wearing a Paisley shawl.

Photograph courtesy of Nordska Museet.

A garment that was subject to fashion as the shawl was, of course, required constant renewal and adaptation to changing fads. By the mid nineteenth century shawls had also spread to people in the lower strata of sociey, becoming a favourite outer garment, since they were easy to wrap around and affordable because no tailoring was required. When the shawl disappeared as a fashion garment, which happened when the bustle replaced the crinoline in the 1870s, it lived on as the most common female folk garment at least until 1900, and in places in Britain even later.

Paisley shawl from the beginning of the twentieth century.

Nanna Snygg from Fleminge.

Courtesy of Nordiska Museet.

Home-woven checked woollen shawls could be found on most farmer's wives and could be used for many purposes, not just as a woman's outer garment. With a shawl, one could always keep warm, so it was suitable for old people shivering in their bedrooms, for swaddling infants on the way to church, or wrapped round a school child with several kilometers to walk to school on an icy morning with snow swirling.

The European copies were strikingly often worn as bridal shawls. This shows how much of an exclusive ceremonial garment the shawl had become. Woven shawls were in turn copied and printed on fabrics, in descending quality from silk to cotton and wool, with patterns that repeated the miribota motif closely or more imaginatively. Yet no matter what the quality, shawls were the best garments for those who could afford them. When shawls went out of fashion in the 1870s, in particular the Paisley shawls, they were not thrown away - they were too good for that! Rather, they were given new functions. They were big enough to serve as door drapes, tablecloths, and piano covers, or they could be converted into a full-length dressing gown or evening coat.

Throughout the twentieth century, from time to time, the shawl made a comeback in fashion. The Paisley pattern remained popular and familiar. For example, most people have owned at least one handkerchief with this pattern. Pashmina shawls remain in demand. Today it is not just teenagers, who wrap a large shawl around their neck during the coldest days.

My new, contemporary ArtCloth pashmina wraps collection, named, “Urban Codes - Series 1”, is based on the current Western revival of tattoos and tattoo body art. It is a limited-edition series which will not be repeated. Click on the following link to view all of my unique scarves - My New Hand Dyed and Hand Printed ‘Urban Codes - Series 1’ Pashmina Wraps Collection.

Reference:

[1] The Power of Fashion: 300 Years of Clothing, Berit Eldvik, Catalog for the exhibition - Power of Fashion, Halmstad (2010).