Preamble

For your convenience, I have listed below other post on Japanese textiles on this blogspot.

Discharge Thundercloud

The Basic Kimono Pattern

The Kimono and Japanese Textile Designs

Traditional Japanese Arabesque Patterns - Part I

Textile Dyeing Patterns of Japan

Traditional Japanese Arabesque Patterns - Part II

Sarasa Arabesque Patterns

Contemporary Japanese Textile Creations

Shibori (Tie-Dying)

History of the Kimono

A Textile Tour of Japan - Part I

A Textile Tour of Japan - Part II

The History of the Obi

Japanese Embroidery (Shishu)

Japanese Dyed Textiles

Aizome (Japanese Indigo Dyeing)

Stencil-Dyed Indigo Arabesque Patterns

Japanese Paintings on Silk

Tsutsugaki - Freehand Paste-Resist Dyeing

Street Play in Tokyo

Birds and Flowers in Japanese Textile Designs

Japanese Colors and Inks on Paper From the Idemitsu Collection

Yuzen: Multicolored Past-Resist Dyeing - Part I

Yuzen: Multi-colored Paste-Resist Dyeing - Part II

Katazome (Stencil Dyeing) - Part I

Katazome (Stencil Dyeing) - Part II

Katazome (Stencil Dyeing) - Part III

Birds and Flowers in Japanese Textile Designs [1]

Bird-and-flower imagery is part of a long and evolving design tradition in Japan. The Japanese reverence for the natural world has its roots in ancient Chinese belief systems that mixed with the animism of Japan’s indigenous Shintō religion and the later influence of Buddhist practices from India and China.

Birds and Flowers 1.

Birds and Flowers 2.

A vocabulary of literary and visual symbols based on observation of nature from an

aesthetic standpoint came to the fore during the Heian period (794-1185). Birds and flowers became

the most popular design motifs for cloth during the Muromachi (1338-1573) and Momoyama (1573-

1603) periods and provided a rich and complex stock of motifs originating from Heian poetry and

courtly traditions.

Birds and Flowers 3.

Birds and Flowers 4.

Since first becoming part of Japan’s cultural awareness, these designs have been used to mark

auspicious events, celebrate the turn of the seasons, indicate rank and nobility, and manifest beauty and refinement. They are fully understood by the entire society and bestow poetry and magic upon the textiles associated with ritual and folk practices and celebrations such as the turning of the lunar new year and weddings, as well as everyday dress.

Birds and Flowers 5.

Birds and Flowers 6.

Japanese textiles integrate both abstract and figurative elements, and the resulting designs are

narrative in quality. Japanese art carries as clear a message and meaning as written language. Like

kanji, the Chinese characters that are part of written Japanese language, the visual elements

combined in a textile design communicate much more than the mere objects they mimic. This results

in a remarkable ability to use complex ideas as the basis for compositions on textiles that are clear in meaning, strikingly rendered, and powerful.

Birds and Flowers 7.

Birds and Flowers 8.

The Japanese use of a character-based (kanji) language would seem to have influenced the art and

design culture, enhancing the richness of meaning the Japanese extract from visual symbols on

clothing and textiles.

Birds and Flowers 9.

Unlike in the West, there are no hierarchical distinctions among the arts in Japan. The artist who designs cloth was and is the equivalent in status of a master ceramist or painter.

References:

[1] https://risdmuseum.org/sites/default/files/museumplus/313138.pdf

[2] Kyoto Shoin, Japanese Style - Textile Dyeing Patterns 4, Nippon Shuppan Hanbai Inc., Kyoto (1989).

Preamble

For your convenience I have listed below other posts on Australian aboriginal textiles and artwork.

Untitled Artworks

(Exhibition - ArtCloth: Engaging New Visions) Tjariya (Nungalka) Stanley and Tjunkaya Tapaya, Ernabella Arts (Australia)

ArtCloth from the Tiwi Islands

Aboriginal Batik From Central Australia

ArtCloth from Utopia

Aboriginal Art Appropriated by Non-Aboriginal Artists

ArtCloth from the Women of Ernabella

ArtCloth From Kaltjiti (Fregon)

Australian Aboriginal Silk Paintings

Contemporary Aboriginal Prints

Batiks from Kintore

Batiks From Warlpiri (Yuendumu)

Aboriginal Batiks From Northern Queensland

Artworks From Remote Aboriginal Communities

Urban Aboriginal ArtCloths

Western Australian Aboriginal Fabric Lengths

Northern Editions - Aboriginal Prints

Aboriginal Bark Paintings

Contemporary Aboriginal Posters (1984) - (1993)

The Art of Arthur Pambegan Jr

Aboriginal Art - Colour Power

Aboriginal Art - Part I

Aboriginal Art - Part II

The Art of Ngarra

The Paintings of Patrick Tjungurrayi

Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri

Australian Aboriginal Rock Art - Part I

Australian Aboriginal Rock Art - Part II

Aboriginal Art - Part II[1]

The art of Aboriginal Australia is the last great tradition of art to be appreciated by the world at large. Despite being one of the longest continuous traditions of art in the world, dating back at least fifty millennia, it remained relatively unknown until the second half of the twentieth century.

Rock painting, Kakadu, Northern Territory, Australia.

The Surrealist map of the world, published in 1929 by the Parisian avant-garde, depicted the size of each country proportionate to the degree of artistic creativity, with the recently discovered riches of the Pacific islands looming large. Australia barely featured.

Note: Even New Zealand has a bigger footprint than Australia.

Art is central to Aboriginal life. Whether it is made for political, social, utilitarian or didactic purposes,and these functions constantly overlap - art is inherently connected to the spiritual domain.

Rock engraving, ca. 500 AD, Mount Camerson West, Tasmania.

The earliest surviving bark paintings date from the nineteenth century, an example of which is a bark etching of a kangaroo hunt now in the British Museum, which was collected near Boort in northern Victoria by the British explorer John Hunter Kerr.

Bark painting housed in the British Museum.

The modern form of bark paintings first appeared in the 1930s, when missionaries at Yirrkala and Milingimbi asked the local Yolngu people to produce bark paintings that could be sold in the cities of New South Wales and Victoria. The motives of the missionaries were to earn money that would help pay for the mission, and also to educate white Australians about Yolngu culture. As the trade grew, and the demand for paintings increased, leading artists such as Narritjin Maymuru started being asked to mount exhibitions.

Mission at Yirrkala.

It was not until the 1980s that bark paintings started being regarded as fine-art, as opposed to an interesting indigenous handicraft, and commanded high prices accordingly on the international art markets. Nowadays, the value of a fine bark painting depends not only on the skill and fame of the artist, and on the quality of the art itself, but also on the degree to which the artwork encapsulates the culture by telling a traditional story.

Bolda Hunter Bim - Barramundi.

Aboriginal Art - Part II[1]

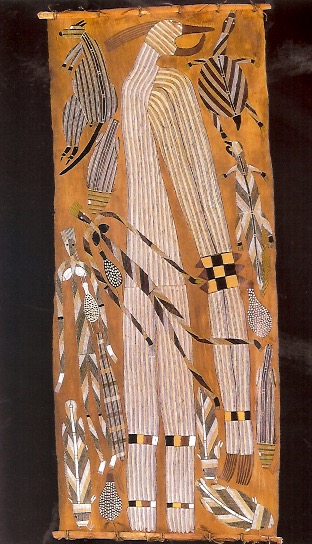

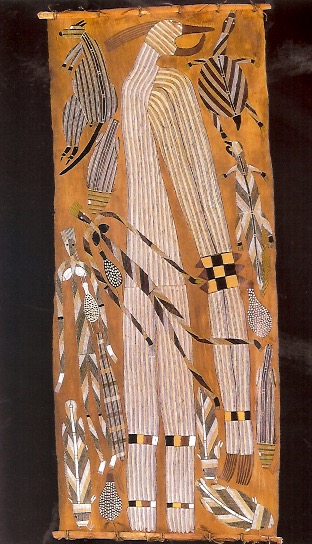

Author, Title of Work: Djawida, Nawura, Dreamtime Ancestor Spirit (1985).

Materials and Techniques: Natural pigments on bark.

Size: 156 x 68 cm.

Collection: National Gallery of Australia.

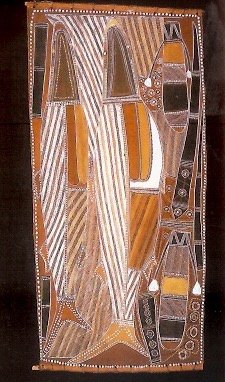

Author, Title of Work: John Mawurndjul, Rainbow Serpent's Antilopine Kangeroo (1991).

Materials and Techniques: Natural pigments on bark.

Size: 189 x 94 cm.

Collection: National Gallery of Australia.

Author, Title of Work: Mick Kubarkku, Dird (1991).

Materials and Techniques: Natural pigments on bark.

Size: 196.5 x 74 cm.

Collection: National Gallery of Australia.

Author, Title of Work: Jack Kala Kala, Balangu, Two Sharks (1986).

Materials and Techniques: Natural pigments on bark.

Size: 130 x 60 cm.

Collection: National Gallery of Australia.

Author, Title of Work: Les Mirrikkuriya, Digging Sticks and Sacred Dilly Bay at Ginajangga (1988).

Materials and Techniques: Natural pigments on bark.

Size: 152 x 93.8 cm.

Collection: Art Gallery, South Australia. Maude Vizard-Holohahn Art Prize Purchase Award (1988).

Author, Title of Work: Tjam (Sam) Yikari Kitani, Wagilag (1937).

Materials and Techniques: Natural pigments on bark.

Size: 126.5 x 68.5 cm.

Collection: Museum of Victoria, Donald Thomson Collection (1988).

Author, Title of Work: Dawidi Djulwarka, Wagilag Religious Story (1965).

Materials and Techniques: Natural pigments on bark.

Size: 84 x 46.5 cm.

Collection: Private Collection.

Reference:

[1] Caruana, Aboriginal Art, Thames & Hudson, 3rd Edition, London (2012).

Introduction [1]

String Theory is a partnership between two textile designers, Meghan Price and Lysanne Latulippe, with Megan specializing in weaving and Lysanne, specializing in knitting.

Megan Price is an artist and woven textile designer. She was born in Montreal and is based in Toronto. Her career encompasses an active art practice, commissioned and collaborative design projects, and she teaches at the Ontario College of Art & Design University in Toronto. Price had a degree in Textile Construction from the Montreal Centre for Contemporary Textiles and a Master of Fine Arts with a specialization in Fibre from Concordia University in Montreal.

Lysanne Latulippe lives and works in Montreal. She has taught at the Montreal Center for Contemporary Textiles since 2005. In 2000, she earned a diploma in Textile Construction. An expert in the field of knit design, she also consults and collaborates with businesses and independent fashion designers.

String Theory [1]

String Theory's scarves and shawls are distinguished by their exclusive pattern designs and by the look and feel of their long-wearing quality. Knitted and woven with yarns such as Peruvian baby alpaca and Italian Merino, these fabrics are a pleasure to live in.

Large black and grey shawl.

As constructed textile designers, String Theory work with the maths and physics of thr fibers, yarns, knitting and weaving to develp structure, pattern and texture. Consequently they are inspired by structures and patterns observed in the built and natural world.

A wonderful black speckled on white background scarf.

Essentially they are interested in how our world comes together and falls apart and the patterns that occur in the process.

A simple woven textile designed scarf. Note the knit design at the end to give the scarf a finality.

Note: The phrase String Theory is borrowed from a theory mostly developed by the late Stephen Hawking. In physics, string theory is a theoretical construct in which the point-like particles in terms of particle physics are replaced by one-dimensional objects called strings. String theory describes how these strings propagate through space and how they interact with each other. It is a discredited theory in physics.

Reference:

[1] K. O'Meara, The Pattern Base, Thames & Hudson London (2015).

Preamble

This is the one hundredth and twelth post in the "Art Resource" series, specifically aimed to construct an appropriate knowledge base in order to develop an artistic voice in ArtCloth.

Other posts in this series are:

Glossary of Cultural and Architectural Terms

Units Used in Dyeing and Printing of Fabrics

Occupational, Health & Safety

A Brief History of Color

The Nature of Color

Psychology of Color

Color Schemes

The Naming of Colors

The Munsell Color Classification System

Methuen Color Index and Classification System

The CIE System

Pantone - A Modern Color Classification System

Optical Properties of Fiber Materials

General Properties of Fiber Polymers and Fibers - Part I

General Properties of Fiber Polymers and Fibers - Part II

General Properties of Fiber Polymers and Fibers - Part III

General Properties of Fiber Polymers and Fibers - Part IV

General Properties of Fiber Polymers and Fibers - Part V

Protein Fibers - Wool

Protein Fibers - Speciality Hair Fibers

Protein Fibers - Silk

Protein Fibers - Wool versus Silk

Timelines of Fabrics, Dyes and Other Stuff

Cellulosic Fibers (Natural) - Cotton

Cellulosic Fibers (Natural) - Linen

Other Natural Cellulosic Fibers

General Overview of Man-Made Fibers

Man-Made Cellulosic Fibers - Viscose

Man-Made Cellulosic Fibers - Esters

Man-Made Synthetic Fibers - Nylon

Man-Made Synthetic Fibers - Polyester

Man-Made Synthetic Fibers - Acrylic and Modacrylic

Man-Made Synthetic Fibers - Olefins

Man-Made Synthetic Fibers - Elastomers

Man-Made Synthetic Fibers - Mineral Fibers

Man Made Fibers - Other Textile Fibers

Fiber Blends

From Fiber to Yarn: Overview - Part I

From Fiber to Yarn: Overview - Part II

Melt-Spun Fibers

Characteristics of Filament Yarn

Yarn Classification

Direct Spun Yarns

Textured Filament Yarns

Fabric Construction - Felt

Fabric Construction - Nonwoven fabrics

A Fashion Data Base

Fabric Construction - Leather

Fabric Construction - Films

Glossary of Colors, Dyes, Inks, Pigments and Resins

Fabric Construction – Foams and Poromeric Material

Knitting

Hosiery

Glossary of Fabrics, Fibers, Finishes, Garments and Yarns

Weaving and the Loom

Similarities and Differences in Woven Fabrics

The Three Basic Weaves - Plain Weave (Part I)

The Three Basic Weaves - Plain Weave (Part II)

The Three Basic Weaves - Twill Weave

The Three Basic Weaves - Satin Weave

Figured Weaves - Leno Weave

Figured Weaves – Piqué Weave

Figured Fabrics

Glossary of Art, Artists, Art Motifs and Art Movements

Crêpe Fabrics

Crêpe Effect Fabrics

Pile Fabrics - General

Woven Pile Fabrics

Chenille Yarn and Tufted Pile Fabrics

Knit-Pile Fabrics

Flocked Pile Fabrics and Other Pile Construction Processes

Glossary of Paper, Photography, Printing, Prints and Publication Terms

Napped Fabrics – Part I

Napped Fabrics – Part II

Double Cloth

Multicomponent Fabrics

Knit-Sew or Stitch Through Fabrics

Finishes - Overview

Finishes - Initial Fabric Cleaning

Mechanical Finishes - Part I

Mechanical Finishes - Part II

Additive Finishes

Chemical Finishes - Bleaching

Glossary of Scientific Terms

Chemical Finishes - Acid Finishes

Finishes: Mercerization

Finishes: Waterproof and Water-Repellent Fabrics

Finishes: Flame-Proofed Fabrics

Finishes to Prevent Attack by Insects and Micro-Organisms

Other Finishes

Shrinkage - Part I

Shrinkage - Part II

Progressive Shrinkage and Methods of Control

Durable Press and Wash-and-Wear Finishes - Part I

Durable Press and Wash-and-Wear Finishes - Part II

Durable Press and Wash-and-Wear Finishes - Part III

Durable Press and Wash-and-Wear Finishes - Part IV

Durable Press and Wash-and-Wear Finishes - Part V

The General Theory of Dyeing – Part I

The General Theory of Dyeing - Part II

Natural Dyes

Natural Dyes - Indigo

Mordant Dyes

Premetallized Dyes

Azoic Dyes

Basic Dyes

Acid Dyes

Disperse Dyes

Direct Dyes

Reactive Dyes

Sulfur Dyes

Blends – Fibers and Direct Dyeing

The General Theory of Printing

There are currently eight data bases on this blogspot, namely, the Glossary of Cultural and Architectural Terms, Timelines of Fabrics, Dyes and Other Stuff, A Fashion Data Base, the Glossary of Colors, Dyes, Inks, Pigments and Resins, the Glossary of Fabrics, Fibers, Finishes, Garments and Yarns, Glossary of Art, Artists, Art Motifs and Art Movements, Glossary of Paper, Photography, Printing, Prints and Publication Terms and the Glossary of Scientific Terms, which has been updated to Version 3.5. All data bases will be updated from time-to-time in the future.

If you find any post on this blog site useful, you can save it or copy and paste it into your own "Word" document etc. for your future reference. For example, Safari allows you to save a post (e.g. click on "File", click on "Print" and release, click on "PDF" and then click on "Save As" and release - and a PDF should appear where you have stored it). Safari also allows you to mail a post to a friend (click on "File", and then point cursor to "Mail Contents On This Page" and release). Either way, this or other posts on this site may be a useful Art Resource for you.

The Art Resource series will be the first post in each calendar month. Remember - these Art Resource posts span information that will be useful for a home hobbyist to that required by a final year University Fine-Art student and so undoubtedly, some parts of any Art Resource post may appear far too technical for your needs (skip over those mind boggling parts) and in other parts, it may be too simplistic with respect to your level of knowledge (ditto the skip). The trade-off between these two extremes will mean that Art Resource posts will hopefully be useful in parts to most, but unfortunately may not be satisfying to all!

Introduction

Different fibers may be blended into one yarn. Filaments may be mixed before twisting; staple fibers may be combined at different stages in the spinning process.

A blended yarn or fabric combines the characteristics of its component fibers or filaments, and so blending can be used to modify performance in a number of different areas. For example, cotton and wool are often blended with nylon and polyester to improve durability; an expensive fiber such as cashmere or mohair is blended with a cheaper fiber such as wool to give an expensive handle for a fraction of the cost; fibers with different dye affinities are blended to give subtle color effects in piece-dyed fabrics.

Some Properties of Blended Fibers

The properties of different yarns and fabrics depend on the component fibers and on the yarn structure.

The different fibers in yarns may be combined in a number of ways. If blending takes place early such as during processing (e.g. during opening) it results in a more intimate and uniform blend. The coarser fiber will yield to the fabric its characteristic touch and handle, masking the effects of any fine and costlier fibers in the blend. If fibers of the same diameter but different stiffness or rigidity are blended, the stiffer fiber, because it resists twisting will remain on the outside of the yarn, and so will dictate the handle characteristics of the fabric. Some spinning processes (e.g. Coverspun) are specifically designed to give a non-uniform distribution of the component fibers. Hence, in this case, each fiber in a 50:50 blend may not contribute equally to the final yarn or fabric properties. In practice, it is therefore very difficult to predict exactly what the characteristics of the blend will be.

Different blend types in a fiber.

Courtesy of reference [1].

Viyella - a non-uniform blend of cotton and wool.

Note: The wool fibers being coarser than the cotton, end up on the outside of the yarn, giving a wool handle to the fabric, which launders like cotton.

Courtesy reference [1].

Blending of fibers is now commonplace in clothing. For example, polyesters have a low affinity for water, since they are hydrophobic. However, because of the absence of water in the fiber polymer system, polyesters cannot dissipate static electricity build, which attracts oily and greasy articles, causing soiling that is difficult to remove. The fiber is resilient and crease-resistant, but tends to feel uncomfortable on hot days, since it cannot absorb perspiration well. An approach in overcoming this uncomfortable feel on hot days is to highly twist the yarn, but with a loosely woven structure. However, the most practical solution is to blend polyester with cotton. The poly/cotton blends have been a success in apparel manufacture (and not only from a cost view point). The mixtures of cotton, and polyester fibers of similar diameter to the cotton fiber, are also crimped with the polyester fibers and are cut into staple lengths to match the cotton staple that is in the blend.

In the blending of polyester and cotton, the cotton fibers provide a crisp, cool handle and the comfort of moisture absorbency. Polyester gives the blend excellent crease recovery and drip-dry properties. However, the major problem with such a blend is pilling. The polyester fibers are stronger than the cotton fibers, and with abrasion during use, will break. They cannot fall away from the fabric since they are “tied down” by strong fibers of polyester. Pill resistant polyester cotton blends have been developed, which entails just weakening the polyester fibers to a similar strength to the cotton fibers.

Cross-Dyeing

Different types of fibers require different types of dyes. So when two types of fibers are blended in a fabric (which often happens) it may be necessary to carry out two dyeing processes, one for each fiber. For example, intimate blends of polyester and cotton are often used. If direct, vat or reactive dyes are used to dye the cotton fibers, the polyester will remain uncoloured. The blend will have soft “heather” effect. If this is what you are after, fine. However, this may not be attractive or even desirable. For smooth, uniform, solid color, the polyester fibers need to be dyed with disperse dyes to the same shade of the cotton. How much dye you use for each component of the blend will vary with the proportion of each component in the blend and even then depending where it lies (e.g. mostly on the outside or mostly on the inside of the textile material). For good uniform dyeing, test strips are the name of the game for each type of blend.

Which Process To Do First

Cotton fibers can be dyed at low temperatures. At high temperatures, direct dyes may leave the cotton fibers, and reactive dyes may decompose. Therefore, dyeing of the polyester fibers, which is carried out under pressure at high temperatures (e.g. 130oC) is performed first.

After thorough rinsing and cleaning to remove excess disperse dyeing reagents, the cotton is dyed at lower temperatures, with the selected cotton dyeing process. Color matching is checked visually during this process, to ensure that the final color obtained is satisfactory.

For blends such as wool and polyester, polyester is done first. The general rule is: the hotter the dyeing process, the later it is performed in the over dyeing processes.

Union Dyeing

Both fibers are dyed simultaneously in the one dyeing process. Hence, each fiber component will uptake the dye to different degrees. Union dyeing assumes that the one dyed process will dye both fibers. For example, reactive dyes can be used with wool and cotton blends.

Reference:

[1] A Fritz and J. Cant, Consumer Textiles, Oxford University Press, Melbourne (1986).